In early January 2026, a quiet announcement from Abuja set off a national conversation that travelled faster than applause ever could. It was not the kind of policy that arrived with sirens or shock headlines, yet it touched a ritual so familiar that many Nigerian parents had stopped questioning it. Graduation ceremonies had become annual fixtures in schools across the country, complete with gowns, printed brochures, hired canopies, photographers, souvenirs, and compulsory levies. What once marked a meaningful academic crossing had gradually turned into a recurring expense, repeated year after year, class after class.

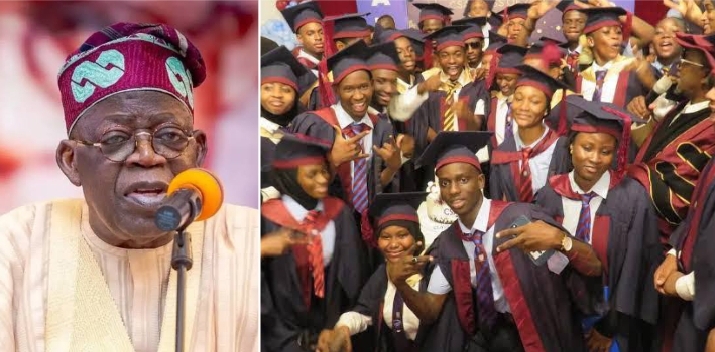

The Federal Government decision to restrict graduation ceremonies to only three academic exit points did not outlaw celebration itself. Instead, it drew a sharp line between milestones and motion. Primary 6, Junior Secondary School 3, and Senior Secondary School 3 were affirmed as the only legitimate moments for formal graduation rites. Everything below these levels was reclassified, not as achievement, but as progression. In doing so, the policy challenged a culture that had normalised ceremonial excess in the name of motivation.

This was not a spontaneous move. The announcement was jointly communicated by the Minister of Education and the Minister of State for Education in January 2026, placing it within a broader reform agenda already underway. It came alongside discussions on textbook durability, standardisation of academic calendars, and cost control within basic education. Yet it was the graduation restriction that struck a nerve, perhaps because it forced families to confront how deeply ritual had been commercialised in the schooling of young children.

What made the policy unusually potent was not its enforcement mechanism but its symbolism. By declaring that nursery and early primary graduations were no longer acceptable, the government implicitly questioned what Nigerians had come to celebrate. Was it learning, or survival through a term? Was it mastery, or mere attendance? The applause had grown loud, but the meaning behind it had thinned, and January 2026 became the moment when the state decided to step in.

The Rise of Ceremonial Inflation in Nigerian Schools

To understand the significance of the ban, it is necessary to trace how graduation ceremonies multiplied across Nigeria’s education system. Two decades ago, graduation was largely reserved for terminal classes. Primary six pupils marked the end of foundational learning. Secondary school leavers closed one chapter and prepared for another. Over time, however, private schools began introducing end of class ceremonies as a branding tool, designed to reassure parents that progress was being made.

What followed was a gradual inflation of ceremony. Nursery pupils wore miniature gowns. Kindergarten classes held valedictory services. Primary one pupils posed for framed photographs declaring them graduates of nothing in particular. Each ceremony carried a cost, often itemised in school bills with little room for negotiation. Parents who resisted risked their children being excluded from group activities or labelled as uncooperative.

By the early 2020s, graduation had become less about academic completion and more about optics. Schools competed on presentation, not pedagogy. Parents compared ceremonies as proof of value for money. Children absorbed the idea that learning was something to be applauded frequently rather than earned steadily. The applause came often, but its weight diminished.

This inflation created a distortion in how education milestones were perceived. When everything is celebrated, nothing stands apart. A child graduating from nursery with pomp and pageantry was being conditioned to expect the same fanfare for every step, leaving little emotional or symbolic difference when genuine academic thresholds were reached. The Federal Government policy of January 2026 directly confronted this distortion.

By limiting ceremonies to three exit points, the government effectively reset the scale of achievement. It reclaimed graduation as a marker of completion rather than continuation. In doing so, it challenged schools to refocus attention on learning outcomes, not ceremonial production, and asked parents to reconsider what progress truly looks like.

The Financial Burden Hidden Behind Celebration

One of the clearest motivations cited by government officials in January 2026 was the financial strain placed on families. Graduation ceremonies had quietly become one of the most unpredictable costs in basic education. Unlike tuition, which could be planned for, ceremonial expenses often arrived suddenly and escalated without transparency. Gowns, certificates, souvenirs, refreshments, venue decoration, and media coverage were frequently bundled into compulsory fees.

For families with multiple children, the burden multiplied. A household with two children in private schools could face graduation expenses almost every year, sometimes twice within the same academic session. Even in public schools, parent teacher associations increasingly organised ceremonies that required financial contributions. Refusal often carried social consequences for both parents and pupils.

The policy framed this issue not as an attack on celebration, but as a protection against unnecessary expenditure. By restricting formal graduation to Primary 6, JSS 3, and SS3, the government sought to create predictability. Parents would know exactly when major ceremonial costs were expected, allowing for better financial planning and reducing the pressure of frequent levies.

This move aligned with a broader understanding of education affordability. Rising inflation, transport costs, and textbook expenses had already stretched family budgets by 2026. Graduation ceremonies below exit levels were increasingly seen as symbolic costs with little educational return. The ban did not eliminate celebration, but it removed the obligation to fund it at every stage.

In essence, the policy redefined responsibility. Schools were reminded that their primary duty was instruction, not event management. Parents were relieved of a recurring expense that had quietly become normalised. And children were shielded from the early internalisation of transactional achievement, where applause is expected regardless of depth or difficulty.

Graduation as Meaning Rather Than Motion

At the heart of the January 2026 policy lies a philosophical question about what graduation is meant to represent. Graduation, by definition, implies completion, readiness, and transition. It signals that a learner has acquired a defined body of knowledge and is prepared to move into a more demanding phase. When applied to non terminal classes, that meaning becomes blurred.

The Federal Government decision sought to restore semantic clarity. Primary 6 represents the conclusion of foundational literacy and numeracy. JSS 3 marks the end of basic education as defined by national policy. SS3 closes the chapter of secondary schooling and opens the door to tertiary or vocational pathways. These are genuine exits, not pauses.

By banning ceremonies below these levels, the policy reinforced the idea that learning is a journey with landmarks, not a series of finish lines. Progress does not always require applause. Sometimes it requires quiet reinforcement, continuity, and focus. This reframing was particularly important in early childhood education, where developmental consistency matters more than ceremonial recognition.

Critics argued that ceremonies motivate children, especially at younger ages. Yet the policy implicitly questioned whether motivation should be externally staged or internally cultivated. When celebration becomes routine, it risks losing its power to inspire. The January 2026 directive leaned toward restraint, suggesting that fewer, more meaningful ceremonies might carry greater emotional and educational weight.

In this sense, the ban was less about prohibition and more about recalibration. It asked schools to teach children that effort accumulates, that milestones are earned, and that not every step forward requires a stage and a microphone. Graduation, once restored to its proper place, could regain its significance as a true academic crossing.

Why January 2026 Was Not an Accident

The timing of the graduation restriction in January 2026 carried a quiet precision that became clearer with reflection. January is when schools reset, parents re budget, and academic calendars are reaffirmed. By placing the policy at the very beginning of the year, the Federal Government ensured that it would shape expectations before ceremonies could be planned, payments demanded, or gowns ordered. It was a preventive move rather than a corrective scramble.

January 2026 also sat at a junction in Nigeria’s broader education reform cycle. Discussions around textbook standardisation, learning quality, and cost control had already been circulating within the Ministry of Education throughout 2025. The graduation ban did not arrive as an isolated instruction, but as part of a layered attempt to restore discipline to basic education expenditure. Announcing it later in the year would have invited confusion, resistance, and claims of retroactive disruption.

There was also a political sensitivity to parental fatigue. By early 2026, household finances were under visible strain. Inflationary pressures, transport costs, and school related levies had become a common source of anxiety. Introducing a policy that visibly reduced non essential spending helped position the government as responsive to everyday pressures rather than detached from them.

Most importantly, January offered moral clarity. It allowed the policy to be framed as guidance rather than punishment. Schools had time to adjust. Parents had time to understand. Children were spared the emotional whiplash of sudden cancellations. In policy terms, it was a soft entry into a hard cultural reset, one that relied more on timing than enforcement.

Private Schools and the Business of Celebration

Private schools sat at the centre of the graduation economy long before the January 2026 announcement. Ceremonies had evolved into revenue streams, branding tools, and marketing showcases. For many schools, especially in urban centres, graduation events doubled as advertisements, displaying facilities, discipline, and perceived value to prospective parents. The ban threatened not just tradition, but income.

Reactions within the private school sector were mixed. Some institutions quickly aligned with the directive, reframing lower class ceremonies as simple end of year parties without formal graduation language. Others attempted semantic gymnastics, renaming events while retaining gowns, certificates, and fees. This revealed the tension between compliance and commercial instinct.

What the policy exposed was how deeply ceremony had been woven into the private education business model. Parents were not just paying for instruction, but for experience. The Federal Government directive challenged schools to decouple learning from spectacle and to justify fees based on academic delivery rather than event production.

Over time, the pressure shifted inward. Schools that complied gained reputational credibility, presenting themselves as disciplined and policy aligned. Those that resisted faced parental scrutiny and regulatory attention. The January 2026 ban thus began to reshape competitive advantage, rewarding restraint over extravagance and subtly redefining what quality education looked like in practice.

Public Schools and the Quiet Normalisation of Excess

While private schools often dominated the graduation narrative, public schools were not immune to ceremonial creep. Parent teacher associations had increasingly filled funding gaps by organising events, sometimes mirroring private school pageantry. Graduation ceremonies became communal projects, justified as morale boosters or community celebrations.

The January 2026 policy applied equally to public institutions, drawing a firm line that many welcomed. For public school administrators, the directive provided cover. It allowed them to decline ceremonial demands without appearing unsupportive or uncooperative. The policy shifted responsibility upward, replacing negotiation with compliance.

In many communities, the ban simplified expectations. Parents no longer felt obligated to contribute to ceremonies that stretched limited resources. Teachers redirected energy toward end of term assessments rather than rehearsals and logistics. The classroom reclaimed time that had been lost to preparation for events.

Perhaps most importantly, the policy exposed how excess had become normalised even where resources were scarce. By reasserting clear exit points for graduation, the government restored proportionality. Public schools were reminded that dignity does not require spectacle, and achievement does not need amplification at every stage.

Cultural Expectations and the Nigerian Love for Milestones

Celebration occupies a powerful place in Nigerian culture. Birthdays, weddings, promotions, and transitions are marked with communal joy. Education milestones naturally absorbed this cultural instinct, turning school progress into social events. The graduation ban therefore intersected not just with policy, but with identity.

For many parents, celebrating their child’s progress is an expression of hope, sacrifice, and pride. Years of school fees, homework supervision, and emotional investment find release in ceremony. The January 2026 directive did not dismiss this impulse, but it did attempt to discipline it, asking families to reserve celebration for moments of true transition.

The policy thus challenged a cultural habit without attacking its roots. It did not forbid joy. It simply narrowed its focus. By elevating Primary 6, JSS 3, and SS3 as the appropriate stages for formal celebration, the government reinforced a hierarchy of milestones rather than erasing celebration altogether.

Over time, this recalibration may deepen rather than diminish meaning. Fewer ceremonies could become more significant. Anticipation could replace routine. Children might come to understand graduation as something awaited, not assumed. In this way, the policy subtly aligned cultural expression with educational structure.

Children and the Psychology of Achievement

One of the least discussed aspects of the graduation ban is its psychological implication for learners. When children are repeatedly celebrated for progression rather than completion, they can develop a skewed relationship with achievement. Effort becomes secondary to recognition, and continuity loses value.

By restricting formal graduation to genuine exit points, the policy reintroduced delayed gratification into the learning process. Children are encouraged to persist without constant ceremonial reward. This mirrors real life more closely, where progress often goes uncelebrated until a threshold is crossed.

Educational psychologists have long argued that intrinsic motivation outperforms external reward in sustaining learning. While the January 2026 directive did not frame itself in psychological terms, its effect aligns with this principle. It reduces the frequency of external validation, nudging learners toward internal benchmarks of success.

In the long term, this shift could reshape how students perceive effort, patience, and accomplishment. Graduation regains its gravity. The gown becomes something earned through endurance rather than attendance. The applause, when it finally comes, carries weight again.

Enforcement Without Force

One striking feature of the January 2026 policy is its reliance on moral authority rather than aggressive enforcement. There were no mass closures, no fines announced, no immediate sanctions publicised. Instead, the directive leaned on clarity, consistency, and administrative expectation.

This approach placed responsibility on school owners and administrators to self regulate. Compliance became a test of institutional discipline rather than fear of punishment. Over time, education authorities could identify outliers through routine inspections and parental reports without resorting to spectacle.

The absence of force also reduced backlash. Schools were given space to adjust. Parents were allowed to adapt emotionally and financially. The policy embedded itself gradually, becoming part of the educational environment rather than a disruptive intrusion.

In this way, the graduation ban functioned less as a crackdown and more as a cultural signal. It announced what the state considered appropriate, then allowed social pressure, professional pride, and parental expectation to do much of the work.

Where the Policy Could Falter

No policy reshapes culture without friction. The graduation restriction faces potential loopholes, particularly in how schools label events. End of year parties, valedictory gatherings, and promotion ceremonies risk becoming unofficial graduations in everything but name.

There is also the challenge of uneven enforcement across states and school types. Education remains a shared responsibility, and coordination gaps could allow selective compliance. Without consistent messaging, parents may receive mixed signals, weakening the policy’s authority.

Another risk lies in over correction. Schools that eliminate all forms of recognition may inadvertently demotivate learners. The policy does not ban acknowledgment, but misinterpretation could lead to emotional austerity. Balance remains essential.

These challenges do not negate the policy’s intent, but they underline the need for clear guidance. January 2026 was a starting point, not a conclusion. How the directive evolves will determine whether it reshapes practice or merely rebrands excess.