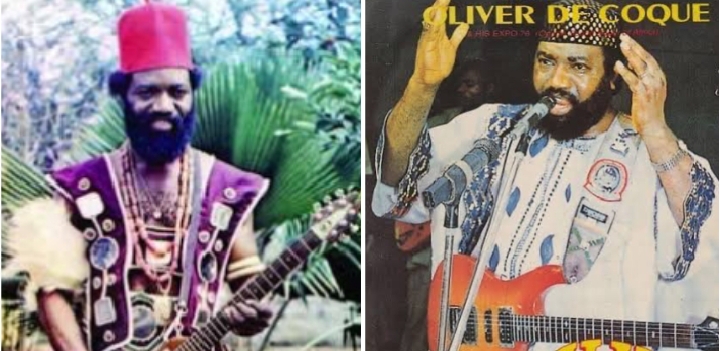

It begins not with words, but with strings. A muted pluck, a silken glide across frets, a trembling note that hovers before finding its rhythm. In the dim half-light of a Lagos nightclub in the late 1970s, the audience sat transfixed as Oliver Sunday Akanite—better known as Oliver De Coque—lifted his guitar and let it sing.

But it wasn’t just music. To his people, it was a riddle. To others, a lullaby. And to those who listened with care, it was something more unsettling—a prophecy. His chants, delivered in highlife cadences, moved like parables: at once entertaining, yet concealing messages about wealth, destiny, unity, and fracture.

The notes seemed to whisper things unsaid, things unfinished. Every song hinted at a Nigeria not yet born, at an Igbo nation still searching for healing, at a future Africa caught between pride and pain. But the prophecy, like his life, was cut short, leaving questions suspended in guitar echoes that refuse to fade.

This is not just a story of a man who strummed. It is a story of chants that tried to speak beyond their time, of a music that clothed prophecy in melody, of an unfinished testament carried on steel strings.

Birth of a Highlife Prophet

Oliver Sunday Akanite was born on 14 April 1947, in Ezinifite, a small town in Anambra State. His birthplace, nestled deep in the cultural heartland of the Igbo, was more than a backdrop—it was a crucible. Here, traditions were not whispered; they were performed in full color: masquerades that danced through markets, drums that mocked kings, and songs that turned gossip into history.

As a child, Oliver absorbed this world not as an outsider, but as one chosen to carry its rhythms. He began with the local ogene and drums, instruments that carried both entertainment and coded speech in Igbo life. But soon the guitar entered his orbit, and with it, destiny. Unlike the talking drum, the guitar was not native—it was an import, a relic of colonial and missionary presence. Yet, in Oliver’s hands, it became something else: an Igbo tongue in metallic strings.

He grew in a Nigeria that was restless, unsure of its identity. Colonial departure left a country stitched from disparate ethnic fabrics, each tugging at the seams. By the time Oliver was a teenager, Nigeria was both proud and wounded, independent yet unstable. These tensions would eventually explode into the Biafran War, but before that, they simmered in music, in identity debates, in the struggle of the Igbo people to define their place in the new federation.

Oliver did not train as a prophet. He was, in the world’s eyes, a musician. But those who knew Igbo storytelling understood: musicians were the chroniclers, the subtle critics, the vessels of collective memory. His destiny was written long before he picked up the guitar.

Highlife’s Golden Thread

In 1920s, along Ghana’s coastal towns, highlife was the marriage of African rhythms with Western instruments, especially brass and guitar. By the 1950s, it had crossed borders, becoming Nigeria’s premier urban soundtrack—refined, modern, yet rooted in African cadence.

Oliver entered this scene in the late 1960s, just as highlife was losing ground to juju in Yoruba Lagos and to the rising storm of Afrobeat in Fela Anikulapo-Kuti’s hands. Yet Oliver refused to surrender the genre. Instead, he reinvented it, branding his own interpretation: Ogene Sound Super of Africa.

Unlike his predecessors, Oliver’s highlife leaned heavily on the guitar. He played not just rhythm, but lead, filling his compositions with fluid riffs that felt like conversations. His guitar “spoke,” echoing the Igbo tradition of instruments as talking beings. But beyond melody, Oliver inserted chants—extended vocal interludes where he praised, admonished, narrated. These chants were not decorative; they were the essence.

Here, highlife became prophecy.

When he sang the names of businessmen and traders, it was not only praise—it was a reminder of their role in rebuilding Igboland after the war. When he chanted about unity, it was not a cliché—it was a warning that Nigeria’s fractures would deepen if ignored. His highlife was less dancehall entertainment, more public prophecy cloaked in danceable grooves.

Yet even as he rose to fame—selling records, touring, appearing on stages across Nigeria and abroad—his message remained curiously unfinished. The chants spoke, but they always seemed to hold something back, as though waiting for the world to catch up.

Chants That Spoke Beyond Music

Oliver De Coque was never in a hurry to sing. Unlike pop musicians who jumped straight into verses, he let his songs breathe. He would strum, repeat a riff, then allow the rhythm section to settle into a groove. Only then would his voice enter—not with melody, but with chant.

These chants were curious. At first listen, they seemed simple: names, praises, blessings. A roll call of traders, chiefs, and patrons. But deeper listening revealed a layered function. His chants were part praise-singing, part historical record, part moral lesson. They were a continuation of Igbo oral tradition, where griots and praise chanters doubled as philosophers, weaving meaning into everyday names.

Take his habit of praising wealthy merchants and businessmen. Many critics dismissed this as sycophancy, a way to secure financial patronage. But to Igbo ears, there was more. By chanting the names of these men, Oliver was cementing them into collective history. He was turning commerce into memory, reminding the community that wealth carried responsibility. His chants became living archives, ensuring that Igbo entrepreneurship—reborn from the ashes of the civil war—was not forgotten.

But his chants also carried shadows. In songs like Identity and People’s Club of Nigeria, his praises danced uneasily with warnings. He lauded the success of the Igbo elite, yet hinted at the dangers of greed, envy, and disunity. His voice often slipped into proverbial tones: what good is wealth if it destroys kinship? What use is progress if it abandons the poor?

This is why Oliver’s music was more than entertainment. For the Igbo trader sweating under the sun in Balogun Market, for the returnee rebuilding burnt-out family homes in Enugu, his songs carried double meaning—comfort and caution, blessing and burden. His chants spoke beyond music; they spoke to a people still nursing wounds, still searching for prophecy in melody.

Between Biafra and Nigeria

The Biafran War (1967–1970) was more than a military conflict; it was an existential scar for the Igbo people. A dream of self-determination drowned in famine and death, leaving survivors with hunger not just of the body but of identity. The postwar slogan—“No victor, no vanquished”—rang hollow in Igbo markets and homes, where rebuilding meant starting from pennies, where discrimination lingered in politics and economy.

Oliver, in his twenties when the war ended, absorbed this atmosphere. His highlife emerged not in the euphoria of victory, but in the bitterness of survival. The chants he wove into music were shaped by this double belonging: Igbo yet Nigerian, Biafran dreamer yet Nigerian citizen.

Listen closely to his lyrics and the war never quite disappears. In Unity, he sings of togetherness, but the plea feels urgent, almost desperate, as if reminding Nigeria of a wound it wished to ignore. In Ndi Igbo Special, he affirms Igbo resilience, turning survival into prophecy—“we are still here, we will not vanish.” His guitar solos, fluid and mournful, often sound like weeping turned into song.

Oliver did not call himself a political prophet. But his highlife was political in its very existence. At a time when Igbo voices were marginalized in federal politics, he ensured that their identity rang loudly on vinyl records, on dancefloors, on radio airwaves. His chants stitched Igbo pride back into Nigeria’s cultural fabric.

And yet, the prophecy remained unfinished. He could sing of unity, but the fractures deepened. He could affirm Igbo resilience, but marginalization persisted. His chants captured both hope and despair, a people caught between a lost Biafra and an uneasy Nigeria.

Oliver De Coque and the Igbo Merchant Kings

If Oliver De Coque was a prophet in music, then his congregation was not in temples but in markets. The Igbo post-war renaissance was not led by politicians, but by traders—men and women who turned shop stalls into empires, who rebuilt family fortunes out of near nothing. In them, Oliver found both muse and message.

His highlife catalog reads like a ledger of Igbo commerce. He sang of wealthy businessmen—Sir Louis Odumegwu Ojukwu, Chief Stephen Osita Osadebe, and dozens of lesser-known names whose success stories were enshrined in his vinyl grooves. Some listeners mocked this as “money music,” suggesting he sang for whoever paid him. But to dismiss his chants this way is to misunderstand Igbo culture.

In Igbo society, praise is not empty flattery. It is an affirmation of value, a reminder that wealth is not private but communal. To call out the names of traders was to bind them to accountability: the community now saw them, and the expectation of generosity weighed on their shoulders. Oliver’s music thus became a bridge between affluence and responsibility, between private wealth and public memory.

More importantly, his chants carried subtle prophecy about the Igbo economic spirit. His praise-songs foretold the rise of Igbo capitalism as a force in Nigeria: markets run by Igbo merchants, real estate ventures stretching across Lagos, and a relentless drive to overcome marginalization through trade. In Oliver’s vision, the merchant kings were not just businessmen—they were rebuilders of identity, custodians of Igbo survival in a federation that once tried to erase them.

But prophecy is always double-edged. For every song that celebrated wealth, there were undertones of caution. Oliver hinted at envy, rivalry, and the danger of excess. He saw how Igbo success often attracted resentment in Nigeria’s fractured politics, how the very spirit that rebuilt Igboland could also provoke backlash. His chants became riddles: celebrate wealth, but beware its shadow. The prophecy of Igbo merchants was powerful—but unfinished.

Global Stages, Local Prophecies

By the late 1980s, Oliver De Coque’s fame had outgrown Nigeria. His guitar, with its hypnotic riffs, carried him into international tours: London, New York, Paris. In these cities, he played for immigrant communities longing for a taste of home, as well as foreign audiences curious about African highlife.

On global stages, his chants took on new layers of meaning. For diaspora Igbo, they were lifelines—voices that reconnected them to the marketplaces and compounds they had left behind. For Western listeners, they were exotic rhythms, proof of Africa’s musical genius. But often, the deeper messages were lost in translation.

A British journalist once described Oliver’s concerts as “joyful praise music,” missing entirely the prophetic edge in his chants. Few outside the Igbo cultural sphere understood that these were not casual name-drops, but coded affirmations of a people’s history. His prophecy was local, and on global stages it risked dilution.

Yet even in this misreading lay a strange kind of fulfillment. By touring abroad, Oliver ensured that Igbo identity entered global circulation. His music was archived in international record stores, studied by ethnomusicologists, and preserved in diaspora communities. The prophecy extended its reach—even if only partially understood.

But again, it remained unfinished. The West heard the guitar, but not the warning. They danced to the groove, but missed the prophecy. And within Nigeria, his global fame did little to resolve the very fractures his chants warned against. Oliver carried Igbo prophecy to the world—but its meaning still waited to be fully decoded.

The Unfinished Prophecy

Oliver De Coque’s career was long, prolific, and filled with acclaim, yet it always seemed to circle around one unresolved truth. His chants called out wealth but warned of greed; they sang of unity but revealed fractures; they praised Nigeria yet clung fiercely to Igbo pride.

By the late 1990s, his music had become a cultural mirror. Nigeria had transitioned from military dictatorship to democracy, but the fractures of ethnicity, corruption, and inequality remained. Oliver’s chants sounded less like celebration, more like reminders that the nation was drifting toward a precipice.

Then, in June 2008, the guitar fell silent. At 61, Oliver De Coque died after a brief illness, leaving behind over 70 albums, countless apprentices, and an unfinished prophecy. His death froze his chants in time—songs that seemed to anticipate a Nigeria still stumbling through corruption, insecurity, and ethnic division.

What was the prophecy left unfinished?

Perhaps it was the dream of true unity, which his chants repeated but Nigeria never embraced. Perhaps it was t.he vision of Igbo wealth lifting all, which remained trapped between generosity and rivalry. Or perhaps it was the simple truth that music alone cannot heal a nation’s scars.

Oliver’s prophecy was unfinished because Nigeria itself is unfinished. His guitar spoke riddles that time has not yet answered. His chants remain suspended, waiting for a generation that might finally decode them.

Legacy in the Digital Dawn

If Oliver’s guitar was silenced in 2008, the digital age has resurrected it. On YouTube, his music videos resurface with thousands of views; on TikTok, younger Nigerians remix his guitar riffs into dance challenges; on Spotify, global listeners stumble upon his catalog alongside Afrobeat giants.

In this new age, his chants have found fresh audiences. Millennials and Gen Z, who never saw him on stage, discover his songs as artifacts of identity. For Igbo youth, they are not just oldies but affirmations: proof that their history has melody, that their commerce and struggles have soundtrack.

Even beyond Nigeria, Oliver’s music resonates. In African studies classrooms in Europe and America, scholars use his highlife to teach about postwar Igbo resilience, about African prophecy hidden in rhythm. DJs sample his riffs in Afrobeat sets, blending his chants with Burna Boy and Wizkid, proving his relevance has not waned.

But the digital revival also underscores the unfinished prophecy. The chants are still there, still coded, still waiting for interpretation. Listeners dance, but not all hear the warning. The guitar has returned, but the prophecy still hangs incomplete.

Reflection: A Guitar That Refuses Silence

In the stillness of a Nigerian night, play an Oliver De Coque record. Let the guitar begin its slow, deliberate riff. Let the chants roll in, calling names, blessing, warning. Listen not with your ears, but with your history.

You will hear more than highlife. You will hear prophecy.

A prophecy unfinished, because it belongs not to Oliver alone, but to Nigeria, to the Igbo people, to Africa itself. A prophecy that says: wealth must serve, unity must be real, identity must endure. A prophecy that remains in the waiting, like a guitar string quivering after the last note.

Oliver De Coque’s chants were never just music. They were whispers of what could be, echoes of what might be lost, reminders of what must endure. His guitar has stopped, but his prophecy refuses silence. It is carried in markets and streaming playlists, in Igbo pride and Nigerian fracture, in every young listener who wonders why the music feels like both joy and warning.

And until Nigeria answers the riddles in his chants, Oliver’s prophecy will remain what it always was: unfinished.