Before Afrobeats had a name, before Lagos streets vibrated with the syncopated pulse of the global phenomenon, there was a sound that existed beyond the ordinary—a sound electric and earthy, sacred and danceable, intimate yet expansive. It was the music of a man whose guitar could speak in Yoruba idioms, whose talking drums whispered ancestral histories into every beat, whose stage presence blurred the line between ritual and rock concert.

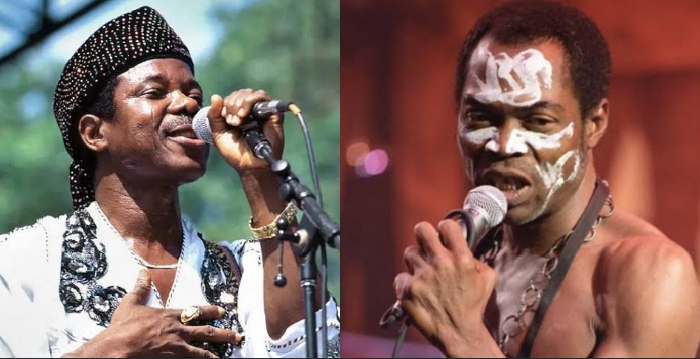

This man was King Sunny Ade, and in the labyrinth of his strings, synthesizers, and percussive mastery, he was laying the tracks for a genre that had not yet been named.

Every note, every chord, every layered rhythm carried the invisible blueprint for Afrobeats. It wasn’t merely entertainment; it was cultural navigation, a sonic bridge from Yoruba villages to the international stage. And though the world wouldn’t recognize it yet, King Sunny Ade’s music was a prophecy—foretelling the global embrace of African rhythms, long before anyone would label the sound as Afrobeats.

From Juju Apprentice to Nigerian Icon

Sunday Adeniyi Adegeye, born September 22, 1946, in Ondo State, Nigeria, began life in a modest household where the rhythms of daily existence were inseparable from the music of the community. In Yoruba culture, music is not decorative—it is woven into the very fabric of life: festivals, rituals, storytelling, even commerce carry rhythmic weight. For young Sunny Ade, the world was already musical, and he was listening.

As a teenager, he apprenticed under Juju masters, learning the intricate fingerpicking, the polyrhythms, and the lyrical cadences that defined the genre. Juju music, already a hybrid of traditional Yoruba percussion, praise singing, and Western instruments introduced during colonial times, offered a canvas for experimentation. Sunny Ade’s genius was not merely in mastery—it was in transformation. He could hear the potential of electric guitars, synthesizers, and modern studio techniques without displacing the ancestral voice embedded in Yoruba rhythms.

By the late 1960s, he had formed his own band, the African Beats, a name signaling both respect for tradition and ambition for global reach. The band’s performances were more than concerts—they were communal experiences, places where Yoruba storytelling met improvisational innovation. Sunny Ade’s compositions integrated the talking drum, the shekere, and the guitar in ways that made Western listeners feel a foreign yet familiar groove.

The Making of a Sonic Innovator

King Sunny Ade’s innovations were subtle yet seismic. He introduced multiple guitar layers to Juju, creating harmonic textures unheard of in Nigerian music at the time. Each guitar line danced around the vocal melodies, mimicking the call-and-response patterns of Yoruba oral tradition. Then came the synthesizers—an instrument foreign to Juju music—but Ade used them with restraint, weaving them into percussion-driven arrangements rather than letting them dominate.

The genius lay in balance: a guitar riff could echo a Yoruba proverb, a drum pattern could mimic the cadence of market life, and a keyboard flourish could evoke the rise and fall of the Niger River itself. Through this synthesis, he was quietly constructing the vocabulary of Afrobeats: polyrhythms, syncopated percussion, melodic interplay, and communal storytelling.

His albums throughout the 1970s, especially “Synchro System” (1983) and “Juju Music” (1982, released internationally), were more than records—they were cultural maps. To listen to them was to journey through Yoruba festivals, Lagos street dances, and imagined urban soundscapes, all while hearing the embryonic heartbeat of a genre that would later conquer the world.

Tracks That Bridged Tradition and Modernity

King Sunny Ade’s music was, in essence, a bridge. Tracks like “Ja Funmi” and “Eje Nlo Gba Ara Mi” layered complex guitar riffs with percussion patterns that mirrored Yoruba drumming ensembles. Vocals flowed like a river, sometimes improvisational, sometimes structured—a musical translation of Yoruba oratory.

But it wasn’t just instrumentation. The lyrical content carried lessons, moral reflections, and social observations. Here, music became didactic and joyous simultaneously. These songs were templates for Afrobeats’ later embrace of story-driven, danceable rhythms, offering grooves that transcended language yet remained deeply African in their heartbeat.

Global Recognition Before Afrobeats Had a Name

By the early 1980s, King Sunny Ade was no longer merely a Nigerian sensation; he was becoming a global phenomenon, though few outside Africa yet understood the roots or significance of his sound. His music arrived in Europe and the United States with an otherworldly vibrancy—an invitation to dance, to listen, to feel a culture centuries old yet startlingly modern.

The turning point was his 1982 album “Juju Music”, released under Island Records, a label known for cultivating world music talent. For many Western listeners, it was the first time they encountered a guitar-driven African sound that married traditional Yoruba percussion with synthesizers, polyrhythms, and layered vocal harmonies. Critics called it exotic, thrilling, and danceable. But for those who listened closely, there was more than novelty: there was the architecture of Afrobeats being drawn in real time.

King Sunny Ade’s 1983 international tour further cemented his reputation. Packed concert halls in London, New York, and Paris bore witness to performances that were ritualistic and ecstatic, precise yet free-form. Audiences marveled at the cascading guitars, the talking drums conversing with synthesizers, and the way dancers seemed possessed by rhythms older than the venues themselves. Ade’s music was a message in motion, carrying Yoruba stories, moral lessons, and the pulse of Lagos streets into foreign ears.

He was not just performing music; he was translating a culture into sound, a feat that few African artists had attempted on such a scale. His success abroad was not just entertainment—it was a revelation: African music could travel without losing its soul, could influence without imitation, could forecast a genre—Afrobeats—that would later sweep global charts.

The Juju to Afrobeats Continuum

To grasp King Sunny Ade’s indirect role in shaping Afrobeats, one must trace the musical lineage. Juju music, with its Yoruba drumming, praise singing, and guitar-driven melodies, served as the fertile soil from which Afrobeats would sprout.

Afrobeats artists today—Fela Kuti’s disciples, Wizkid, Burna Boy—may sound distinct, but the DNA of Sunny Ade’s grooves, improvisational guitar lines, and layered percussion runs silently beneath the surface. He showed that African music could be polyrhythmic yet accessible, rooted yet cosmopolitan, storytelling yet endlessly danceable.

His experimentation with Western instruments, studio production techniques, and global touring created a template for future artists. Whereas many traditional musicians resisted fusion, Ade embraced it without compromise. The result was a musical elasticity, one that allowed Afrobeats to absorb hip-hop, R&B, pop, and electronic elements decades later, without losing its African heartbeat.

Cultural Ambassadorship Through Music

King Sunny Ade was not only a musician but a cultural ambassador. His songs were imbued with Yoruba philosophy—morality, community, respect for ancestors—but also social commentary. Lagos markets, Nigerian elections, urban migration, and the joys and hardships of everyday life were filtered through intricate rhythms and playful, wise lyrics.

By presenting Yoruba culture on an international stage, Ade showed that African music could communicate complex identity, history, and values, all while remaining irresistibly rhythmic. His concerts, albums, and international presence became lessons in cultural diplomacy, bridging gaps between continents through sound.

King Sunny Ade’s Sonic Legacy in Modern Afrobeats

Today, the echoes of Sunny Ade’s innovations resonate across Afrobeats tracks. From Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat fusion to Burna Boy’s contemporary interpretations, the traces of Juju’s polyrhythms, cascading guitars, and Yoruba storytelling are evident. Sampling, homage, and stylistic borrowing by contemporary artists underscore his invisible yet omnipresent influence.

Afrobeats artists inherit more than rhythm—they inherit a philosophy of musical mobility and cultural integrity. Sunny Ade demonstrated that music could traverse borders, evolve without erasing origins, and remain human in its storytelling. In a sense, every global Afrobeats hit is a continuation of the path he began laying decades ago.

Philosophy Behind the Sound

King Sunny Ade’s music was not just entertainment; it was living philosophy. Juju music, in his hands, became a medium for communal storytelling, spiritual reflection, and improvisational brilliance. His approach to composition—layering guitars, percussion, and synthesizers—was as much about listening as playing, responding to rhythms like a conversationalist, translating Yoruba idioms into musical forms.

Improvisation was central. Ade’s performances were fluid, adaptive, and communal, reflecting Yoruba ideas of fluidity in society and the interplay of individual and community. In essence, his music was both map and mirror: it charted a path forward for African music while reflecting the society from which it sprang.

Challenges and Triumphs: The Road Less Traveled

For all the international acclaim, King Sunny Ade’s journey was far from smooth. Navigating the Nigerian music industry of the 1970s and 1980s required more than talent—it demanded resilience, diplomacy, and the ability to thrive amid political, economic, and cultural turbulence.

Nigeria during this period was a nation emerging from military rule, grappling with economic instability and social change. The music industry lacked robust infrastructure: record labels were underfunded, royalties were inconsistently paid, and piracy ran rampant. Even internationally, African artists were often pigeonholed into “world music” categories that exoticized rather than understood their work. Ade faced a subtle yet persistent challenge: how to maintain the authenticity of Yoruba Juju music while gaining global acceptance.

Yet he persevered. The 1982 release of Juju Music in the United States marked a triumph of artistic integrity over commercial compromise. Sunny Ade insisted that his music retain Yoruba lyrics, traditional percussion, and polyrhythmic guitar structures, even when Western producers suggested simplification for broader appeal. He chose fidelity to culture over instant marketability—a decision that would ensure his long-term legacy, even if it slowed short-term global dominance.

The touring life brought its own trials. Transcontinental travel, intense performance schedules, and the responsibility of representing an entire continent weighed heavily on him. Yet every stage became a laboratory, a place where he tested new rhythms, observed audience reactions, and refined his sonic innovations. His triumphs were not measured in chart positions alone but in the invisible seed of influence he planted, which decades later would grow into the sprawling, global Afrobeats ecosystem.

Contemporary Influence: The Invisible Mentorship

Walk into a Nigerian music studio today, and you’ll hear traces of King Sunny Ade in subtle ways—in the finger-picked guitar riffs, the cascading percussion patterns, and the communal, call-and-response vocal arrangements. Artists like Burna Boy, Wizkid, Tiwa Savage, and even Skepta in cross-cultural collaborations carry forward the Juju blueprint, often unconsciously.

For instance, Burna Boy’s layered percussion and rhythmic phrasing echo Ade’s pioneering polyrhythmic guitar-percussion interplay, while Wizkid’s melodic flow reflects the Yoruba cadence and storytelling traditions embedded in Juju music. Even the global “Afrobeats” label, which emerged decades after Sunny Ade’s first international tours, is conceptually indebted to his vision: African music that is both rooted and cosmopolitan, accessible yet profoundly African.

Sampling and homage further reinforce his legacy. Tracks in contemporary Afrobeats, hip-hop, and electronic music occasionally incorporate guitar lines or rhythmic motifs reminiscent of Ade’s signature style. In interviews, many artists acknowledge that their musical intuition is informed by the foundations laid by Juju innovators, even if they never explicitly studied Sunny Ade’s work.

His influence extends beyond sound: it is an ethos of musical integrity, cultural fidelity, and innovation through adaptation. King Sunny Ade demonstrated that African artists could assert global relevance without erasing identity—a philosophy that modern Afrobeats artists live and evolve today.

Philosophical Underpinnings: Music as a Living Organism

King Sunny Ade’s music is not static; it is organic, evolving, and communal. Each performance transforms the composition, each drumbeat interacts with the audience, and each guitar line negotiates space with vocal improvisation. In Yoruba culture, music is an extension of life, reflecting social hierarchies, moral lessons, and communal memory. Sunny Ade internalized this philosophy, allowing it to guide his innovations.

Improvisation in his work is a dialogue between past and present: ancestral rhythms converse with modern instrumentation, and Yoruba proverbs find expression in guitar riffs. In essence, every song is a living organism, breathing, adapting, and influencing future generations. Afrobeats, as a genre, inherits this organism, mutating and thriving on a global stage while retaining its African DNA.

Enduring Legacy: Listening to the Future in the Past

King Sunny Ade’s contribution to Afrobeats is less about direct credit and more about the invisible threads that connect generations. Without Juju’s polyrhythms, layered guitars, and Yoruba storytelling embedded in pop consciousness, Afrobeats might have sounded vastly different—or arrived decades later.

As Afrobeats dominates global charts, festivals, and streaming platforms, Sunny Ade’s fingerprints remain embedded in the soundscape: in rhythmic cycles, melodic intuition, and the seamless balance of tradition and innovation. He did not merely create music; he crafted a cultural framework, a blueprint that allowed African music to travel across oceans, languages, and generations.

To listen to King Sunny Ade is to hear the future reverberating in the past, to feel the pulse of Afrobeats before it had a name, and to understand that musical innovation is both a product of heritage and imagination. Every riff, drum pattern, and vocal inflection is a reminder: Afrobeats was built on a foundation of Yoruba ingenuity, Juju sophistication, and the vision of a man unafraid to bridge worlds.

Final Thoughts: Echoes of the Unnamed Future

To stand in front of a King Sunny Ade concert is to witness time folding in on itself. Centuries of Yoruba rhythms, stories of market life, ancestral echoes, and communal joys converge in a single cascade of sound.

One hears history, improvisation, and prophecy simultaneously: a music that remembers the past while envisioning the future. Afrobeats, in its global celebration, is merely the flowering of seeds planted decades earlier, seeds nourished by Ade’s intuition, discipline, and reverence for tradition.

To listen to his recordings today is to hear Afrobeats before it existed—to sense the pulse of a global phenomenon still unnamed, still evolving, still indebted to the visionary who dared to let his guitar speak in Yoruba. The world dances today not just to Afrobeats, but to a dream King Sunny Ade was composing decades before anyone knew it needed to exist.

In the echo of every riff, in the layering of every drum, in the cadence of every vocal line, his legacy endures: Afrobeats is probably his inheritance, the world’s stage his canvas, and the heartbeat of Africa his gift. And perhaps that is the truest measure of greatness—not in charts or awards, but in the invisible tracks laid for a future yet to be imagined, the sound of possibility resonating long before it had a name.