On humid Lagos nights in the late 1990s, when diesel fumes tangled with the laughter of radio hosts and the air crackled with the promise of something new, two men were building Nigeria’s first entertainment empire without even knowing it.

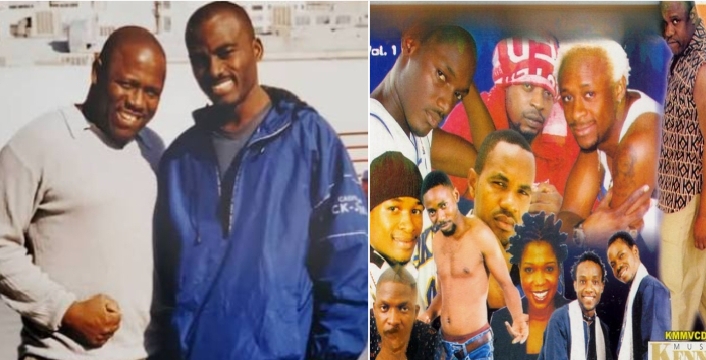

The studio light at AIT Jamz blinked red — On Air. The clock ticked toward 8:00 p.m., and from inside that glass booth, the city began to listen. Kenny Ogungbe — known to everyone as Keke — leaned into the mic, his baritone voice rippling across transistor radios from Ikeja to Ajegunle. Beside him, Dayo Adeneye — D1, calm and sharp-eyed — cued the next track with the ease of a man who knew that sound could change memory.

Then came that anthem: “Welcome to Kennis Music — The Beat of the Moment.” And just like that, a new kind of fame began.

This was no ordinary radio program. It was theatre without faces, marketing without scripts, and gospel for a youth culture that had never been told it could own the airwaves. Lagos didn’t yet have Afrobeats as we know it; it had fragments — a singer here, a rapper there, a dream trying to find structure. But Keke and D1 were building that structure, one broadcast at a time.

They were not just OAPs. They were architects of a new possibility — one where music could carry the authority of politics, the glamour of Nollywood, and the faith of a generation.

Every Friday night, under the warm yellow bulbs of AIT Jamz, they introduced artists who had never been photographed under studio light. They gave names to voices. They sold dreams like records.

This is the story of how Kennis Music, the first entertainment dynasty of modern Nigeria, transitioned from dominance to memory, and why its legacy remains hidden in the DNA of today’s sound.

The Broadcast Before the Boom: Lagos in Transition

To fully grasp Kennis Music, one must return to a pre-Internet Nigeria — a nation of cassette tapes, radio jingles, and televised countdowns that felt like live ceremonies. The late 1990s marked a peculiar cultural crossroad: Nigeria was emerging from military rule, Lagos was rediscovering its nightlife, and technology was slowly dismantling the monopoly of state-controlled media. In that tension of rebirth, Keke and D1 found their calling — not as mere broadcasters, but as cultural architects.

Their platform, AIT Jamz, later evolved into PrimeTime Africa, a music program that married radio discipline with television glamour. It became a classroom for the nation’s first generation of video consumers. Young Nigerians, previously confined to foreign pop culture, now saw local stars — Eedris Abdulkareem, 2Face Idibia, Tony Tetuila, Plantashun Boiz — on screen with production value and flair. Keke and D1 were the gatekeepers, the faces behind the transformation.

At a time when access to international music was controlled by imports and bootlegs, PrimeTime Africa created a bridge. The duo didn’t just play songs; they curated a national consciousness. The show’s jingle, its neon visuals, and their rapport gave Nigerian music a professional face. Long before social media defined celebrity, Keke and D1 taught artists to understand brand, narrative, and presence.

The broadcast became a ritual — Friday evenings when homes paused to watch two men translate the dreams of a new generation. They weren’t just presenting; they were pioneering a sound economy that would later evolve into today’s entertainment industry.

The Birth of a Label: When Vision Became Enterprise

It was only a matter of time before the broadcast empire became a business. In 1998, Kennis Music was born — a label that blended the polish of corporate media with the raw energy of Nigeria’s underground sound. For many, it was an impossible dream: a locally owned record company with national reach and international ambition.

Under Keke’s meticulous leadership and D1’s media strategy, Kennis Music became the epicenter of Nigeria’s early 2000s pop culture. Artists like 2Face Idibia, Eedris Abdulkareem, Tony Tetuila, Essence, and Jaywon became household names through their ecosystem. Each song, each album release, came with the kind of publicity only an in-house broadcast network could provide.

But Kennis Music wasn’t just producing hits — it was engineering careers. It introduced visual branding to a market that previously didn’t understand it. Artists suddenly had photoshoots, stylized videos, and structured rollouts. Even their album covers — embossed logos, futuristic fonts, coordinated colors — hinted at a new level of professionalism.

The duo’s synergy was unmistakable: Keke, the strategist with a radio executive’s precision; D1, the showman with political tact and charisma. Together, they blurred the line between media and music. At its peak, Kennis Music wasn’t just a label — it was a movement, a prototype for what Nigerian entertainment could become.

The Prime of Pop: When Kennis Ruled the Air

By 2002, the Kennis empire had become unavoidable. Their artists dominated the Headies, the Nigerian Music Awards, and every chart that mattered. 2Face Idibia’s Face2Face (2004) and Grass 2 Grace (2006) symbolized not just personal success but national renaissance. The hit single African Queen didn’t just travel — it carried the sound of a nation that had found its rhythm.

Behind the glitter, Keke and D1 maintained a disciplined media formula. PrimeTime Africa became a promotional engine for Kennis artists. Their airtime dominance gave them cultural leverage — the power to dictate taste, trends, and trajectory. Their studio on Toyin Street in Ikeja became a pilgrimage site for artists seeking recognition.

At the same time, they redefined music management in a country still struggling with copyright enforcement and piracy. Kennis Music’s contracts were more formalized than most, and the label insisted on artist development. While others saw music as hustle, Keke saw it as industry.

The Rise and Rule — Inside the Machinery of Kennis Music

In every cultural revolution, there is a quiet architecture behind the noise — a rhythm of meetings, money, and meaning that decides who gets to be heard. For Kennis Music, that architecture was built on belief: that Nigerian music could be packaged, promoted, and priced with the same seriousness as any international act.

The Power Behind the Booth

Long before record deals became PDF contracts and distribution was counted in streams, Kennis Music operated like an old-school family business powered by media. Their office was part newsroom, part radio station, part artist camp — a hybrid ecosystem that thrived on synergy.

Keke’s voice commanded authority; D1’s presence created balance. Together, they were the perfect duet of vision and diplomacy — one playing the creative maestro, the other managing corporate bridges.

Artists signed under Kennis didn’t just get recording deals; they entered a mentorship crucible. It was not unusual for Keke to personally vet lyrics, adjust melodies, or decide which song should lead an album. Every rollout had a broadcast strategy attached — a radio premiere, an AIT feature, a video debut on Primetime Africa, and carefully orchestrated appearances.

What the world saw was glamour; what insiders saw was precision. The Kennis empire was built on media vertical integration before the term existed in Nigerian entertainment. They owned their own TV show, radio platforms, and distribution networks. Every hit track could be amplified instantly. Every new artist had guaranteed visibility.

That control created a dynasty.

The Artist Factory

At its core, Kennis Music was an assembly line of cultural exports — not in the industrial sense, but in how carefully it shaped stars to fit the evolving Nigerian psyche.

Take 2Face Idibia — a soft-spoken boy from Jos who, under Kennis, became the continent’s most recognizable face of pop sincerity. His image was carefully curated — stylish but relatable, gentle but bold, a lover who represented the optimism of post-military Nigeria.

Then there was Eedris Abdulkareem, the opposite in temperament — fiery, outspoken, and political. His Jaga Jaga era proved that Kennis didn’t shy from controversy. In fact, they harnessed it. The song became both a national anthem and a political debate. It wasn’t just about the lyrics; it was about what they symbolized: the first time Nigerian pop directly challenged power.

Kennis also created space for women in a male-dominated industry. Essence, KSB, and Eedris’s protégées represented the softer edge of the label — faith-infused, emotional, deliberate.

The formula was simple: build artists as personalities, not just singers. Every music video told a story; every album carried moral undertones; every public appearance contributed to a myth.

It was entertainment with conscience — a blueprint that combined American media discipline with Nigerian spirituality.

The Primetime Advantage

What made Kennis unstoppable in the early 2000s wasn’t just its artists — it was Primetime Africa, the weekly TV program that became a launchpad for an entire generation of musicians.

Before YouTube, before streaming, before Instagram Live — that one-hour show was the closest thing to global visibility. Artists who appeared there were instantly validated. Performances from unknown acts in Surulere would be broadcast to millions across Africa through satellite TV.

The show’s tone was both celebratory and serious. Interviews were warm but structured. Keke and D1 didn’t just talk to stars; they introduced them to the nation.

It wasn’t rare to see acts like Styl-Plus, Plantashun Boiz, Ruggedman, or Tony Tetuila become household names overnight because of that platform. Kennis had effectively merged two worlds — the intimacy of radio and the spectacle of television — creating a feedback loop that multiplied influence.

By 2005, the label had become synonymous with success.

When people said “Kennis Music!”, it wasn’t just a name — it was an exclamation mark.

The Business of Trust

Behind the creative explosion was a carefully managed business ecosystem. Kennis Music operated in an era when Nigerian entertainment lacked structure — few contracts were legally binding, and intellectual property laws were loosely enforced.

Keke and D1 stepped into that vacuum as trusted mediators between artists and the corporate world. They convinced telecom companies, beverage brands, and even government agencies that Nigerian music was a viable investment.

Keke’s Rolodex became the industry’s lifeline. He could call a sponsor in the morning, secure a concert venue by noon, and premiere an artist’s video by evening.

That blend of media influence and corporate access made Kennis the de facto cultural ministry of early-2000s Nigeria. They weren’t just producing stars — they were scripting the new national soundtrack.

And yet, in the midst of that success, the seeds of change were quietly sprouting.

The digital world was coming. And unlike Kennis’s structured empire, it didn’t respect hierarchy.

When the Beat Changed — Rival Labels, Digital Disruption, and the Kennis Transition

The year was 2006. Nigeria’s entertainment landscape was glowing with new energy. A younger generation was finding its own rhythm — not in studios filled with engineers and tape reels, but on laptops balanced on dining tables.

Suddenly, sound was no longer about structure. It was about freedom. And in that freedom, Kennis Music, once the sun around which everything revolved, began to face the dawn of its twilight.

A New Sound, A New Rebellion

While Keke and D1’s empire was still running on disciplined marketing and broadcast domination, a group of younger producers was busy crafting an entirely different sound — looser, funkier, more urban.

Don Jazzy and D’banj were leading the insurgency. Their label, Mo’Hits Records, did something Kennis never did: it made music that sounded like nightclubs, not radio programs.

Where Kennis prized lyrics and message, Mo’Hits glorified rhythm and indulgence. Their songs weren’t meant to inspire; they were meant to infect.

“Why Me,” “Tongolo,” “Booty Call” — each release arrived like a rebellion against the moral structure that had defined the Kennis era. The visuals were sexier. The language was looser. The branding was digital.

Kennis Music, though respected, began to sound like an older sermon in a world that now wanted a party.

At the same time, Storm Records was nurturing acts like Naeto C, Sasha, and Ikechukwu, introducing cosmopolitan hip-hop into the mainstream. Chocolate City brought a more northern perspective with M.I Abaga and Jesse Jagz, using sharp lyricism to carve intellectual territory.

By the late 2000s, the musical alphabet had changed. The rhythm was no longer about message — it was about motion.

The Digital Tsunami

Then came the real rupture: the internet.

By 2008, blogs like NotJustOk and Linda Ikeji’s Blog were replacing traditional broadcast media as gateways to stardom.

Artists no longer needed a gatekeeper; they needed a data plan.

A 16-year-old in Surulere could upload a track on MySpace and get discovered. A song could go viral on forums without ever playing on AIT or RayPower. The old empire of controlled access was dissolving.

Kennis Music — built on the power of television and radio monopoly — struggled to translate that influence into a world of downloads and hashtags.

Their strength had always been control: a tight distribution chain, curated releases, physical CD sales, structured artist promotion. But the internet dismantled control. It democratized fame.

Where Keke and D1 once planned every rollout like a state ceremony, new-age artists were dropping singles on whim — and fans were deciding the hits themselves.

In the old world, Kennis was king. In the new one, everyone was their own label.

The Cultural Disconnect

There was another shift, more subtle but equally seismic — the audience’s mindset.

The youth who once grew up watching Primetime Africa were now digital natives, more influenced by MTV Base and YouTube than terrestrial TV.

Kennis’s aesthetic — disciplined visuals, moral undertones, mature presentation — suddenly felt out of sync with the reckless spontaneity that now defined pop culture.

Audiences no longer wanted sermons packaged as entertainment; they wanted escapism, digital validation, and the rush of immediacy.

Music videos that once premiered on Primetime Africa were now debuting on YouTube hours after they were shot. Artistes were no longer waiting for television approval — they were their own content channels, their own publicists, their own media brands.

The shift wasn’t just technical; it was psychological. The Kennis generation had taught Nigerians to dream through structure — the Mo’Hits generation taught them to improvise.

Suddenly, the same gatekeeping that once gave Keke and D1 power became a disadvantage. The empire they had built on discipline and broadcasting ethics could not thrive in a world where virality required chaos.

By 2010, Primetime Africa’s once-unshakable rhythm was beginning to fade into nostalgia. The show was still respected, the hosts still revered — but the culture had moved elsewhere.

Younger fans no longer associated credibility with television; they associated it with visibility — and the internet had endless room for that.

In essence, Kennis Music was built for the analog century, while Nigerian pop was stepping fully into the digital age.

The Transition Years

Still, it would be wrong to call what happened next a collapse. Keke and D1 didn’t vanish — they evolved, albeit quietly.

They pivoted toward broadcast ownership, doubling down on what they knew best: radio and television. Kennis FM became a new experiment — a nostalgic sanctuary for listeners who still longed for curated sound and responsible entertainment.

They continued producing the Kennis Music Easter Fiesta, a yearly event that remained one of the longest-running music festivals in Nigeria. For nearly a decade, it was a reminder that the dynasty still held emotional weight, even if the charts had moved on.

Meanwhile, their earlier artists — now independent or under other managements — continued to echo the Kennis legacy in their work. 2Face Idibia evolved into 2Baba, a national symbol of endurance and humility.

Sound Sultan carried the same conscience-driven music into the next decade. Even artists who were never directly signed under Kennis acknowledged its cultural footprint.

Kennis had become the spiritual DNA of Nigerian pop — the school that taught everyone else the rules, so they could later learn how to break them.

But behind that legacy was a quiet awareness: that time had moved faster than structure.

The Quiet Rift

Every great empire carries its own contradictions, and Kennis was no exception. For years, whispers of creative differences, contract disputes, and evolving artist loyalties surfaced around the label.

The story of 2Face’s exit in particular became a cultural milestone — not for the controversy it carried, but for what it symbolized: the coming of artist independence.

When 2Face launched Hypertek Entertainment and continued his success without Kennis, it showed that even the most loyal protégés eventually needed autonomy.

The same independence that Kennis had once fought for — a world where Nigerian music could stand on its own — was now being claimed by its students.

To many observers, that was poetic justice. To Keke and D1, it was simply the natural rhythm of progress. They had built an ecosystem where structure mattered; their proteges had turned that structure into freedom.

But freedom, as always, comes with loss.

The loss of control. The loss of ownership.And, most painfully, the loss of centrality.

The Industry’s Changing Heartbeat

By the mid-2010s, the industry Kennis helped build had transformed into a machine of constant reinvention. Artists like Wizkid, Davido, and Burna Boy — who grew up during the Kennis era — were now operating under a new paradigm: global streaming, influencer culture, and personal branding as currency.

These younger stars didn’t wait for airplay; they created their own demand through social media storytelling. Their audience wasn’t the family huddled around TV at 9 p.m. — it was the individual listener scrolling through a phone at 3 a.m.

Kennis, once the lighthouse of national culture, now found itself watching from the shore as the new ships of Afrobeats sailed globally.

It wasn’t irrelevance — it was transition.

Keke and D1 had been pioneers of the first infrastructure that made Nigerian entertainment possible. But infrastructure rarely gets applause after the city is built.

Their contribution had shifted from frontline to foundation. And that, perhaps, was the most dignified fadeout of all.

Legacy in Echo — The Enduring Influence of Keke, D1, and the Kennis Blueprint

Every empire leaves behind an afterglow — a kind of cultural radiation that lingers long after its visible power fades.

For Kennis Music, that glow never really dimmed; it simply diffused, absorbed into the DNA of an industry that now speaks its language without even realizing it.

The Mirror Stage — When the World Began Watching Nigeria

Before the digital tide swallowed everything, Kennis Music had already expanded beyond being just a record label. Through Primetime Africa, they became the country’s unofficial cultural window to the world. Every Sunday, when the show aired, homes across Lagos, Enugu, and Abuja tuned in — not just for local gossip, but to glimpse how Nigerian music was beginning to stand beside global acts.

When the Grammys happened each year, it was Keke and D1 who translated that distant glamour for Nigerian audiences.

They brought the red carpet to living rooms. They dissected who wore what, who won what, and — more importantly — where African artists stood in that global equation.

For many young Nigerians in the early 2000s, their first understanding of global entertainment journalism came through Primetime’s Grammy coverage. The camera would sweep across Hollywood’s biggest names — Beyoncé, Usher, Alicia Keys — but then linger lovingly on the rare African face in the crowd, reminding viewers that the distance between Lagos and Los Angeles was shrinking.

Keke and D1 didn’t just report; they interpreted. They spoke of 2Face Idibia’s international nominations with the reverence of a national project. When Nigeria’s own Femi Kuti got Grammy nods, they covered it like a national election. Their tone was one of belonging — that subtle insistence that Nigerian talent was not an outsider to the global stage, but a latecomer finally finding its place.

Through those years, Primetime Africa functioned like a cultural embassy. It trained the audience to see Nigerian music as part of a global continuum — not a provincial artform. And that perception shift mattered. It became the mental groundwork for later crossovers: for Wizkid standing beside Beyoncé, for Burna Boy holding his Grammy aloft, for Tems writing global hooks.

Yet, while they prepared others for the future, Kennis itself remained rooted in the past.The irony was profound. As they broadcasted stories of the world changing, they were becoming an emblem of what was being left behind.

The Echoes in Afrobeats

Every time Wizkid walks into a sponsorship meeting, every time Davido announces an endorsement, every time Burna Boy curates a narrative around Afro-fusion — Kennis is somewhere in the background.

The idea that artistes should control their image, package their sound, and think strategically about visibility — that’s pure Kennis doctrine.

Where Don Jazzy brought charisma and contemporary sound, Keke and D1 had earlier brought credibility and framework.

Their insistence that music must have direction is what allowed the later generation to build empires without chaos.

In the current Afrobeats ecosystem — global tours, brand partnerships, international collaborations — the spirit of Kennis lives in the details: the press kits, the marketing teams, the calculated album drops, the emphasis on artist development.

Even the new obsession with media storytelling — documentaries, behind-the-scenes footage, viral interviews — echoes what Primetime Africa perfected two decades earlier.

It is as though the future took their script, remixed it, and renamed it “content strategy.”

The Human Legacy

For Keke and D1, the legacy isn’t just in what they built — it’s in who they became.

After the high tide of the 2000s, both men remained visible yet grounded.

They turned into elder statesmen of entertainment — always approachable, always analytical, still radiating the calm assurance of men who’ve seen the full cycle of fame.

Keke continued to nurture younger talents through his media network and consulting. His voice still carries that weight — the kind that can make even silence sound intentional. D1 transitioned fluidly into business and public service, but his presence at cultural events still commands reverence.

Together, they embody a rare kind of longevity — the kind that doesn’t depend on constant reinvention, but on relevance that matures.

They became, in essence, custodians of an era. And every generation needs its custodians — people who remind it that before virality, there was vision.

Nostalgia as Legacy

Over time, nostalgia became Kennis Music’s greatest currency. Not the sentimental kind — but the kind that deepens respect.

Their catalog, though quieter today, still plays like a time capsule of pre-digital Nigeria: when love songs were earnest, when lyrics mattered, when TV jingles carried moral undertones.

At concerts, when 2Baba performs “African Queen,” the crowd’s reaction is as much about the song as it is about memory. People remember where they were the first time they heard that track on Primetime Africa. They remember the logo spinning, Keke’s voice introducing it with reverence.

That shared nostalgia forms a bridge between generations — linking the analog pioneers to the digital revolutionaries.

For today’s Afrobeats fans, Kennis Music is mythology. For those who lived through it, it’s history. And for Keke and D1 themselves, it’s legacy — a living echo still shaping the moral architecture of Nigerian entertainment.

Leaving With This: When Silence Became the Final Masterpiece

What remains of an empire after the applause fades isn’t its noise — it’s its shape. Kennis Music’s story is no longer about the songs they released or the artists they crowned. It’s about how they taught a restless nation to take its own art seriously.

The fadeout wasn’t tragedy; it was tempo. They knew when to stop playing so the rhythm could travel further. The industry that once orbited around them didn’t replace them — it evolved through them. And that is the quiet brilliance of their exit: they disappeared at the precise moment Nigeria’s sound became unstoppable.

No monument bears their faces, yet every concert stage, every award night, every young producer who believes his sound can cross oceans — that’s the real monument. The dynasty didn’t crumble. It became the air around the music.

In the end, the fadeout of Kennis Music is proof of something rare — that legacy isn’t always loud. Sometimes it lingers as atmosphere — unseen, uncredited, but eternal.