There is a hush in the air when September slides quietly into November, when the streets of Ibadan, Lagos, and smaller towns across southwestern Nigeria begin to shimmer with the faint pulse of anticipation. Streetlights flicker differently, markets close a fraction earlier, and conversations, no matter how mundane, carry an unspoken urgency.

It is the ember-month season—a period suspended between the weight of the year past and the promise of the year ahead. In this liminal space, a single song can shift the collective heartbeat of a community, pulling them into reflection, prayer, and the shadowy apprehension that another twelve months always carries. That song is Odun Nlo Sopin.

Its opening chords are a soft whisper, barely noticeable to the casual listener, but to those raised on the rhythms of the CAC Good Women Choir of Ibadan, it resonates with ancestral memory. The lyrics, sung in measured Yoruba cadence, speak of the end of a year, the perils left behind, and the unseen trials that might yet befall.

Listeners experience it as a mirror of their own uncertainties. Will the coming year bring the blessings for which they have prayed, or will unspoken misfortunes find their way through unnoticed cracks? Within each note, each pause, is the fragile heartbeat of humanity caught between survival and aspiration.

The Ember-Months and Nigerian Cultural Consciousness

The term “ember months” in Nigeria is more than a temporal marker; it is a cultural phenomenon. Spanning September to December, these months carry historical, economic, and spiritual weight. For centuries, Nigerian societies have treated this period as a time of reflection, preparation, and cautious optimism. Traditional farmers, merchants, civil servants, and students alike understand that the ember months are a liminal space—a bridge between what has been endured and what is yet to come.

It is within this cultural consciousness that Odun Nlo Sopin finds its resonance. The song is not merely performed; it is experienced. Its cadence mirrors the uneven rhythm of human life—sometimes gentle, sometimes urgent. Listeners internalize the song as a moral compass, reminding them to examine their actions and seek reconciliation with family, neighbors, and the Divine.

Anthropologically, this corresponds with rituals of closure and renewal, a concept that spans many African societies where song, speech, and collective observance are intertwined.

The fear it evokes is tied directly to this cultural context. Ember months historically coincide with increased travel, heightened economic activity, and a notable uptick in accidents, social conflicts, and public health crises. These realities, coupled with traditional beliefs about spiritual vulnerability at the year’s end, create a fertile ground for songs that simultaneously caution and comfort. By invoking a collective awareness of mortality and divine oversight, Odun Nlo Sopin functions as both cultural anchor and social mirror, reminding individuals that the year’s end is a time for humility and preparation.

Voices Behind the Anthem: The Choir and the Birth of Odun Nlo Sopin

Behind every song that becomes more than just music—especially one that frames the emotional landscape of an entire season—are the lives, struggles, and aspirations of its creators. Odun Nlo Sopin is no exception. The song emerged from the CAC Good Women Choir of Ibadan, a choir whose reputation in southwestern Nigeria has been built on decades of meticulous vocal training, spiritual devotion, and community engagement. The women of this choir were not merely performers; they were custodians of memory, bearers of ancestral harmonies, and interpreters of Yoruba cosmology through sound.

At the forefront was Mrs. D.A. Fasoyin, a figure whose life story mirrors the song’s duality of hope and caution. Known for her unwavering faith and exacting musical standards, she cultivated a choir that could move congregations not only through lyrics but through the emotional resonance of rhythm and tone. Mrs. Fasoyin drew from decades of church service, the oral traditions of her youth, and an acute awareness of the societal anxieties that came with the ember months. Her leadership ensured that Odun Nlo Sopin would not just be a hymn, but a reflection of collective consciousness, a sonic mirror of communal hope and fear.

The song itself arose from a layering of history, tradition, and lived experience. Yoruba Christian music has long interwoven secular sensibilities with devotional purpose, and in this context, the choir adapted older CAC hymns dating back to the 1940s. They infused them with new verses that spoke directly to contemporary anxieties—the uncertainty of life’s journey, the unspoken perils of the year, and the moral imperative to reflect and reconcile before the year concludes. The result was a composition that simultaneously honored the past, addressed the present, and anticipated the future.

Performing Odun Nlo Sopin required more than technical skill. Choir members internalized the seasonal psychology of their audience, modulating tone, pace, and volume to mirror the subtle tension of ember-month reflection. Each rehearsal was a ritual in itself, a preparation not just of voice but of spirit. By the time the song was performed during the closing months of the year, it carried the weight of decades of preparation, the lived experience of the performers, and a carefully calibrated ability to move listeners into introspection. It was a song born from biography, history, and devotion—a creation that would resonate far beyond the walls of the church.

Decoding the Lyrics: The Dual Pulse of Fear and Hope

The opening lines of Odun Nlo Sopin immediately establish a tone that is both reverent and urgent:

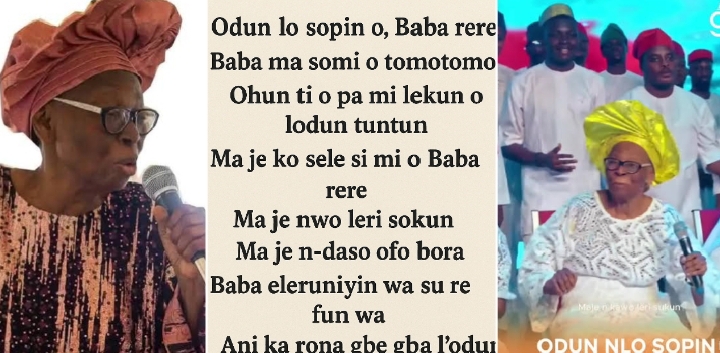

” Odun lo sopin o, Baba rere

Baba ma somi o tomotomo”

Here, the listener is confronted with the literal acknowledgment that the year is ending—a temporal marker that carries weight beyond calendars. Within the Yoruba worldview, the passage of time is never neutral; it is imbued with spiritual significance and moral accountability. By invoking “Baba rere” (Good Father), the song positions the Divine as both witness and protector, inviting introspection. There is an undercurrent of fear here, subtle but persistent: life is fragile, the year has brought trials, and what has not been reconciled may yet bear consequence. Yet, interwoven with this caution is the promise of guidance and care—the hope that the Good Father will intervene, sheltering the faithful from harm as the new year begins.

The next lines deepen this duality:

“Ohun ti o pa mi lekun o lodun titun

Ma je ko sele si mi o Baba rere”

These words articulate personal vulnerability. “What could cause me sorrow in the new year” is a direct recognition of human fragility. In the ember months, fear is communal: roads are busier, life’s uncertainties multiply, and reflections on mortality intensify. Yet, the repeated plea—“Do not let it happen to me, Good Father”—introduces a tone of hope, a spiritual negotiation with fate. The listener is invited into an intimate dialogue between fear and trust, a delicate acknowledgment of life’s precariousness alongside an enduring faith that protection is possible.

The lyrics then turn to a deeply human plea:

“Ma je nwo leri sokun

Ma je ndaso ofo bora”

Here, the singer moves from abstract vulnerability into a raw, intimate appeal: “God, don’t let me cry; suffering not be my portion.” This is not merely a reflection on potential misfortune; it is the voice of every individual confronting the year’s end with the weight of past hardships and the uncertainty of what lies ahead. The fear is tangible—acknowledging that life can wound, that losses and trials are inevitable. Yet the hope is equally vivid. By calling upon the Divine in this direct, heartfelt manner, the song becomes a sanctuary, a way of negotiating with fate itself.

Finally, this verse elevates the personal to the communal:

“Baba eléruniyin wa su re fun wa

Ani ka rona gbe gba l’odun to wole”

This refrain binds individual fear and hope to collective experience. “Father of all praise, bless us” is not merely a personal prayer; it is an invocation for community protection and shared survival. The communal voice amplifies the emotional resonance of the song, reminding listeners that the passage of time is experienced collectively. The lyrics reflect a society that navigates fear and hope together, using music as a vessel for spiritual preparation, ethical reflection, and communal solidarity as one year closes and another looms.

In essence, every phrase of Odun Nlo Sopin is a mirror—reflecting human anxiety, moral responsibility, and the persistent hope that guides communities through the shadowy threshold of the ember months. It is this lyrical architecture, delicately balancing fear and hope, that transforms a seasonal hymn into an enduring cultural anthem.

Ember-Month Rituals, Community Practices, and Music

In Nigeria, the ember months are a season of heightened ritual, communal gatherings, and reflective practices. From Lagos to Ibadan, and stretching across towns and villages in the southwest, the period from September to December carries an unspoken rhythm. It is a time when calendars are revisited, debts are settled, and households prepare both materially and spiritually for the approaching year. Within this cultural choreography, music—especially songs like Odun Nlo Sopin—becomes a thread that binds ritual, reflection, and community together.

Church services during these months are unlike those in other seasons. Choirs perform with an intensity that mirrors both anticipation and solemnity. The Good Women Choir’s rendition of Odun Nlo Sopin often opens gatherings, setting a tone that oscillates between fear and hope. Congregants are drawn into a shared temporal consciousness; the song’s message prompts both introspection and outward engagement. Listening becomes an act of communal alignment: households, neighbors, and friends collectively acknowledge the year’s trials while seeking divine favor for the months ahead. In this way, the song transforms from a musical performance into a ritual instrument, orchestrating collective reflection in a culturally resonant manner.

Beyond church walls, the song permeates domestic and social spaces. Families play it in living rooms, small markets hum its refrains, and community gatherings often begin or end with its melody. In many homes, parents remind their children of the song’s moral underpinnings, explaining that the words are not merely a musical tradition but a spiritual guidepost. Through these practices, Odun Nlo Sopin becomes an aural marker of the season, signaling the interplay of responsibility, vulnerability, and hope. Its presence encourages households to reconcile unresolved conflicts, settle outstanding obligations, and approach the new year with intention and mindfulness.

Parting Words: Under the Ember-Month—Fear and Hope in a Song

Under the ember-month, time itself feels fragile, as if the year’s final days hover between shadow and possibility. Odun Nlo Sopin captures this suspended reality—not by recounting events or offering predictions, but by giving voice to the tension that fills the hearts of those who listen. In its lyrics and melody, fear is not just acknowledged; it is lived, embodied, and transformed into vigilance. Hope, in turn, is not abstract—it is the deliberate act of seeking protection, of trusting that one’s tears and trials need not define the year ahead.

The song lingers in memory like the faint glow of twilight: a reminder that endings are thresholds, that reflection and preparation are sacred acts, and that communal consciousness can guide individual endurance. Its resonance under the ember-month is a quiet insistence that, even when life’s uncertainties press close, humans can navigate the border between what has been and what is to come with intention, courage, and faith.

In the stillness after the last notes fade, listeners are left with a dual awareness: the weight of the past year and the fragile promise of the next. Odun Nlo Sopin does not erase fear, nor does it offer certainty. Instead, it transforms the end of the year into a space where vulnerability becomes shared, hope becomes actionable, and humanity stands at the threshold of tomorrow—aware, reflective, and ready.