To many Lagosians today, Ikorodu is a bustling commuter town where the hum of danfos drowns out memory. But peel back the asphalt of the highways and the clamor of motor parks, and you find a place that once stood as Lagos’ restless frontier — a land where hunters tracked game through dense forests, where warriors defended fragile borders, and where traders ferried salt, palm oil, and slaves across the waterways with the defiance of a people unwilling to be subdued.

This article delves into the human story of Ikorodu’s rebels — not rebels in the crude sense of chaos, but as hunters who rebelled against hunger, warriors who rebelled against conquest, and traders who rebelled against stagnation.

They were the men and women who made Ikorodu more than just a satellite to Lagos; they made it a frontier, a contested borderland where survival meant daring to challenge the tide of history.

From Forest Settlement to Frontier Town

Ikorodu began humbly. Oral tradition speaks of Awori-Yoruba hunters, led by figures such as Olofin Ogunfunminire, who cleared the first compounds along the ridges overlooking Lagos Lagoon in the early 1600s. The name “Ikorodu” itself is said to mean “Oko Odu” — literally “the farm settlement” — born out of farmland carved from the thick forest.

The first settlers were not kings or generals but farmers and hunters. They cultivated yam, cassava, and vegetables in shifting plots, and they hunted antelopes, bush pigs, and guinea fowl in the surrounding wilderness. What they could not grow, they traded: palm oil pressed from nearby groves, raffia mats, smoked fish, and goat skins. The lagoon gave them access to traders from Epe, Badagry, and even the coast of Benin.

But what made Ikorodu different was not its farming or fishing — it was its position. Nestled between Lagos Island and the deep Yoruba interior, Ikorodu became a natural meeting ground, a checkpoint between the coast and the hinterland.

By the 1700s, caravan routes stretched from the Ijebu kingdom through Ikorodu down to the growing market town of Lagos. Salt from the Atlantic, cloth from Portuguese traders, kola nuts from the north, and enslaved people from warring towns all passed through its clearing.

That frontier geography — neither fully coastal nor fully inland — would shape its destiny.

The Coming of the Wars

The nineteenth century shattered the fragile peace of Yoruba land. Following the fall of Oyo Empire in the early 1800s, towns scrambled for survival. The collapse unleashed waves of warlords, displaced peoples, and slave raiders. Ibadan rose as a military powerhouse, Abeokuta became a fortress of Egba resistance, and Lagos was pulled between Atlantic commerce and British imperial ambitions.

Ikorodu, small as it was, could not escape. Its location between Ijebu Ode, Epe, and Lagos made it a prize for rival powers. More importantly, its people refused to be trampled.

By the 1840s, Ikorodu had become a town of fortified compounds, with mud walls surrounding clustered family courtyards. Hunters now carried dane guns instead of bows. Traders traveled in groups, armed against raids. Every household trained its young men for war, because war was no longer an event — it was the atmosphere.

The great test came during the Ijebu–Egba conflicts and the wars tied to the control of Lagos. The Ijebu kingdom wanted Ikorodu firmly under its thumb. But Ikorodu’s chiefs — particularly figures such as Chief Sodeke and the war leader, Olofin — resisted. They began to build alliances, sometimes with Lagos, sometimes with Egba refugees, and at times with mercenaries.

Ikorodu’s resistance was not just political. It was existential. For a small town, survival meant holding the walls, manning the gates, and never appearing weak before larger powers.

The Ikorodu War of 1854–1855

The defining rebellion came in the mid-nineteenth century: the Ikorodu War (1864–1865). This conflict, though often overshadowed by the more famous Ijaye War or Kiriji War, was crucial to Lagos history.

The spark came when Ikorodu openly challenged the authority of the Ijebu kingdom. The Ijebu considered Ikorodu their vassal, but Ikorodu traders refused to pay certain tolls on the caravan routes. They began trading directly with Lagos merchants, bypassing Ijebu control. In the tense atmosphere of Yoruba politics, that was enough to provoke war.

The Ijebu assembled forces and marched on Ikorodu. For weeks, the town became a fortress under siege. Women smuggled food through hidden paths, while warriors took positions on the walls. Oral accounts say the hunters of Ikorodu, skilled in the forest, ambushed enemy supply lines and used the terrain to their advantage.

British influence also hovered over the conflict. By 1851, Britain had bombarded Lagos and was beginning to assert control over the coast. Ikorodu, hostile to Ijebu tolls, found common cause with Lagos merchants who wanted free passage of goods. Some historians suggest that Ikorodu’s defiance indirectly aided Britain’s consolidation of Lagos, because weakening Ijebu control served imperial interests.

The war ended with Ikorodu bloodied but unbroken. It established the town’s reputation as a rebel frontier — too stubborn to crush, too strategic to ignore.

Trade, Women, and the Marketplace of Defiance

Ikorodu was not only a town of warriors. Its backbone was commerce, and its lifeblood was women. The great markets of Ikorodu — Oja Ikorodu — became centers where palm oil, smoked fish, cloth, and later cocoa, were exchanged.

Women traders carried goods along forest paths and across canoes to Lagos. They built networks with Ijebu women, with Epe fishermen, and with Hausa kola nut merchants from the north. Even in times of war, the market never fully stopped. Oral histories recall how women risked their lives, slipping through blockades to supply food during the Ikorodu War.

Trade was rebellion. Every basket of yams smuggled past Ijebu toll collectors, every canoe of palm oil shipped directly to Lagos, was an act of defiance. Ikorodu’s traders proved that economic stubbornness could be as potent as military resistance.

Colonial Shadows

By the late nineteenth century, Britain had formally annexed Lagos (1861) and expanded influence inland. For Ikorodu, this was both an opportunity and a threat. The colonial government wanted stable trade routes, free of Ijebu tolls. Ikorodu benefited — its traders flourished as Lagos expanded into a global port.

But colonialism also weakened the old warrior traditions. The British outlawed certain raids and imposed peace on warring towns. Ikorodu’s hunters now found themselves pushed toward farming and commerce. The walls that once guarded the town began to crumble. Missionaries established schools, teaching reading and writing in place of war drills.

Still, Ikorodu remained restless. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, its sons joined anti-colonial movements, its traders resisted exploitative taxes, and its farmers clashed with colonial officers over land. The spirit of defiance lived on, though its weapons had changed.

Legacy of a Rebel Town

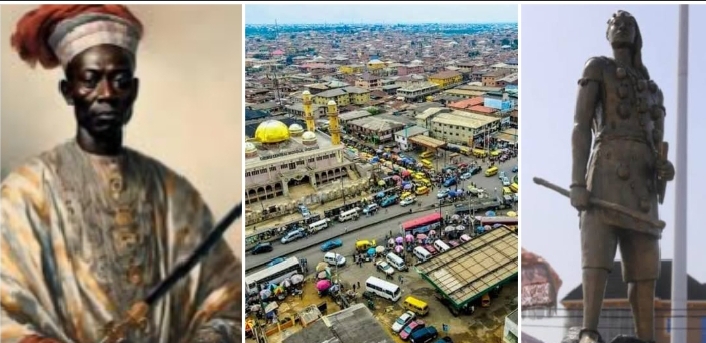

Today, Ikorodu is swallowed into the expanding belly of Lagos State. Its once forested ridges are covered with cement houses and motor parks. But its past still whispers in festivals, in family lineages, and in the pride of its people.

The descendants of those hunters and warriors still remember that their town stood against stronger powers. The marketplace still hums with the same stubborn energy of women who once smuggled food through sieges. The lagoon routes remain active, linking Ikorodu to the larger Lagos economy.

Ikorodu’s story is not just a local chronicle. It is the story of how small towns shape empires. Lagos might never have become the giant city it is today without the defiance of Ikorodu, a frontier town that forced open trade routes, resisted domination, and carved its place into history with blood and grit.

Conclusion: The Frontier That Made Lagos Possible

History often remembers capitals and empires but forgets the stubborn villages that made their existence possible. Ikorodu was one such village — a rebel outpost of hunters, warriors, and traders who fought not for glory but for survival.

They remind us that Lagos, Africa’s largest city, was not only built by colonial governors, wealthy merchants, or foreign traders. It was also shaped by ordinary men and women who refused to bow, who fought for control of their trade routes, and who stood behind mud walls with muskets, watching the horizon for enemy smoke.

Ikorodu was never just a settlement. It was a statement. A refusal. A frontier that declared: we will not be erased.