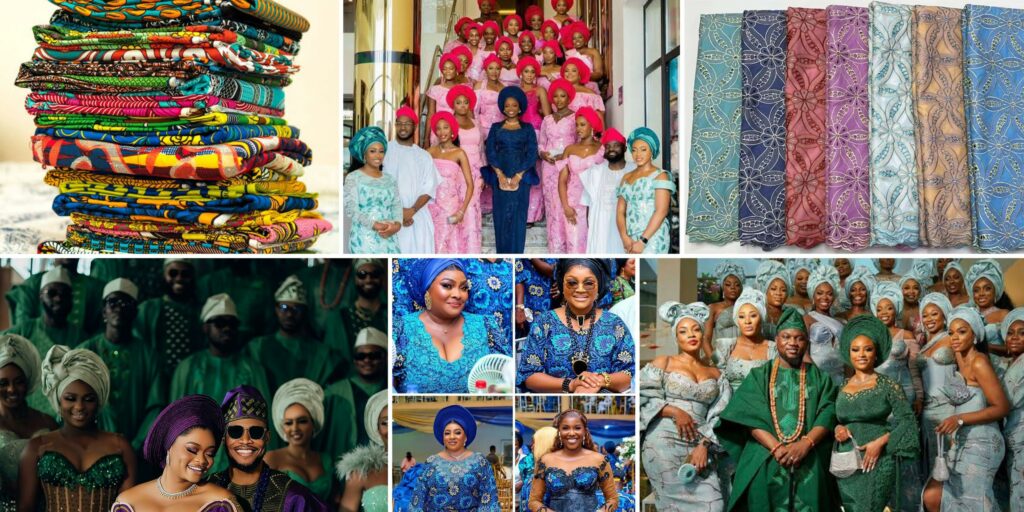

If there’s one thing Nigerians know how to do, it’s party. And not just any party, I’m talking owambe, the kind of celebration where the music is loud, the food is endless, the drinks keep flowing, and the fashion? Oh, the fashion is a whole production. And at the center of that fashion spectacle is one thing: aso ebi.

Aso ebi is no longer just fabric. It’s an industry, a status symbol, and sometimes, a source of both joy and stress. Let’s break down how something as simple as “family cloth” became big business, why it divides opinions, and where it’s headed in a Nigeria that’s always changing.

1. Where It All Began

The phrase aso ebi literally means family cloth in Yoruba. Back in the day, it meant just that… cloth members of the same family wore to show solidarity during big events like weddings, naming ceremonies, and funerals. Over time, it spread beyond bloodlines. Friends, neighbours, church members, even colleagues started joining in.

And then came owambe, Yoruba’s signature way of partying that is big, loud, and unapologetically extra. Aso ebi and owambe became inseparable. You couldn’t really show up at one without the other.

2. More Than Just Matching Outfits

At first glance, aso ebi might look like “just matching clothes.” But culturally, it’s deeper. Wearing that fabric is saying: I belong here. I’m with this group. At weddings, it tells you who’s on the bride’s side and who’s supporting the groom. At funerals, it shows solidarity with the family.

But it doesn’t stop at unity. Over time, aso ebi has become a way to signal status and taste. The richer the lace, the shinier the sequins, the more intricate the embroidery, the louder the unspoken message of: my people came correct.

3. The Big Business Behind Aso Ebi

Here’s the part people sometimes forget. They forget aso ebi is not just about culture; it’s also a serious business ecosystem. Think about it:

• Fabric vendors and wholesalers import or stockpile lace, Ankara, velvet, brocade, and aso-oke.

• Tailors and designers get flooded with orders weeks before the party.

• Gele specialists and make-up artists make sure heads and faces are on point for the big day.

• Photographers and videographers cash out documenting the glamour.

• Event planners and caterers tie it all together.

• Even DJ’s, MCs, Live bands, and musicians aren’t left out of the big day.

When you buy aso ebi, you’re not just buying fabric. You’re feeding a whole economy of creatives and service providers.

4. A Multi-Billion Naira Market

Nigeria’s fashion industry is estimated at billions of dollars annually and aso ebi is one of its driving forces. Every week, across the country, hundreds of parties require new fabric orders. Multiply that by tailors’ fees, accessories, styling, transportation to the venue, gifts for the celebrant and you see why aso ebi is not just tradition but a cash cow.

Designers have clocked this too. Many now create premium aso-ebi collections with traditional textiles like aso-oke and adire, rebranding them as luxury fashion. What used to be “just” family cloth is now runway-worthy.

5. How Much Does Aso Ebi Really Cost?

Let’s be real: aso ebi is not cheap. The price depends on the fabric and quality:

• Ankara or cotton prints: ₦2,000–₦6,000 per yard.

• Mid-range brocade or lace: ₦20,000–₦30,000 for 5yards.

• High-end guipure or Swiss lace: ₦100,000 and above

And don’t forget tailoring. A simple style might cost ₦10,000 – ₦25000, while elaborate dresses can climb way higher. For some guests, it’s affordable. For others, it’s a heavy burden, especially when multiple aso-ebi invites hit back-to-back.

6. From Solidarity to Social Pressure

Here’s where the criticism kicks in. Aso ebi was once about solidarity. Now, it’s sometimes seen as show-off culture. An average person’s wedding aso ebi for instance used to range around ₦15,000 – ₦20,000 but now, it’s double or triple. Buying expensive fabric and paying a tailor is one thing, but being expected to do it repeatedly? That can feel more like pressure than joy.

For lower-income guests, aso ebi can even mean skipping an event entirely to avoid embarrassment. There are countless stories of people who couldn’t afford the fabric and chose to stay home rather than look “out of place.”

What started as family cloth has become, in some eyes, a form of exclusion.

7. How COVID-19 Changed Owambe Culture

When the pandemic hit, owambe culture suffered. No gatherings meant no aso ebi. Vendors, tailors, and photographers felt the pinch. Even after restrictions eased, inflation and naira depreciation made fabric more expensive.

Some celebrants now cut back on lavish aso ebi sales or scrap them altogether. Smaller, less flashy parties are increasingly common.

8. Aso Ebi in the Age of Instagram

If COVID slowed things down, Instagram and WhatsApp sped them up. Bridal parties now use group chats to coordinate payments and fabric distribution. Vendors advertise on Instagram, complete with style inspiration, giveaways, and international delivery.

The aso ebi market is now global. From London, Houston, and Toronto, owambes all thrive on this digital convenience and it’s not limited to only Nigerians in diaspora.

9. Beyond Yoruba: A Pan-Nigerian Tradition

Though aso ebi started with the Yoruba, it has spread across Nigeria. Igbo, Hausa, and other ethnic groups embrace it too, often blending in their own textiles. Diaspora communities also use aso ebi to hold on to cultural roots.

What began as a Yoruba custom has become a national and global phenomenon.

10. Aso Ebi: Beauty, Business, and Burden

At the end of the day, aso ebi is many things at once:

• A booming industry that powers fashion and events.

• A cultural glue that unites families and friends.

• But also a social pressure point that sometimes divides and excludes.

It’s beauty and burden at the same time. Tradition and big business.

Conclusion

At its heart, aso ebi is about community. It says: these are my people, and I’m standing with them. But today, it’s also about status, fashion, and economics.

The challenge is balance. Can we hold on to the unity of aso ebi while easing the pressure it puts on guests’ pockets? Can we celebrate our culture without turning it into competition?

Bottomline is, as long as there are owambes, there will be aso ebi.