The wind coming off Bar Beach that September morning carried more than salt and sea spray—it carried history. Lagos had not yet awakened, yet thousands were already on the move, pressing toward the shoreline, drawn by rumor and vengeance. Somewhere behind the military barricades, a man once called the Doctor of Robbery stood shackled, his smile fixed, his fate sealed. The city, swollen with fear and fascination, waited to watch the curtain fall on a season it could neither forget nor forgive. This was not simply an execution; it was an exorcism. Lagos, a city that had lived months in terror, was about to stare its nightmare in the face.

It had been less than two years since Ishola Oyenusi’s name first crept into police files, yet in that short time it had grown into folklore. The whispers spoke of a robber who dressed like a gentleman, who courted danger with the same charm he used on women, who could walk into a crowd moments after a heist and smile like a movie star. To some, he was the embodiment of defiance; to most, he was a symbol of how fragile the city’s order had become. The guns that once guarded warehouses and banks had turned inward, protecting homes, churches, and trembling families.

Now, as the sun edged over the Atlantic, Lagos prepared for a spectacle that would end an era. Soldiers adjusted their rifles. Reporters set up cameras. In the crowd, children perched on their fathers’ shoulders, too young to know they were watching history’s grim theater.

Somewhere in the distance, Ibadan stirred—the other city that had known the robber’s shadow. This was the morning when two cities, long held hostage by fear, would finally breathe again.

The Making of a Myth: Oyenusi’s Early Years

Long before the police dossiers, before the headlines and the fear, Ishola Oyenusi was a boy with restless eyes. Born around 1940 in Lagos, his childhood fell into that uncertain stretch between colonial rule and independence. The city was expanding—factories, new schools, the bright mirage of modern life—but not every family could keep pace. Oyenusi’s schooling stopped early; work came in the form of errands, street hustles, and eventually small thefts that the law ignored. He learned young that confidence could open doors honesty could not.

By his twenties, he had built a reputation as a “fixer”—someone who could acquire whatever a man desired, from spare car parts to fake documents. Friends said he loved dressing sharply, quoting English phrases he picked up from newspapers, and insisting he would someday be rich enough to ride through Lagos without stopping for anyone. That ambition, reckless and unanchored, became his compass. The first robbery—by later police accounts—was not planned as violence. He and an accomplice stole a doctor’s car; when the owner resisted, the pistol went off. The doctor died, and a petty thief became a murderer.

Oyenusi’s world narrowed after that. Each new heist demanded another lie, another weapon, another loyal follower. He found both danger and devotion among the unemployed youth drifting through post-civil-war Nigeria. In them he saw what he had been: angry, ambitious, excluded. In him they saw what they wanted to become—fearless. By 1969, he had a gang, a code, and a city learning his name. The myth was forming: Oyenusi, the dashing bandit who laughed in the face of death.

Doctor of Robbery: How Charisma Became a Weapon

The nickname “Doctor of Robbery” was first used half in jest by a journalist after the police listed “Dr. Ishola Oyenusi” on a seized identity card. It stuck because it fit. He was a man who diagnosed his society’s weaknesses with surgical precision—its trust, its disorder, its hunger for spectacle—and exploited them. Lagos in the early 1970s was booming but brittle; returning soldiers and jobless youths filled its streets, and inequality widened faster than the bridges connecting the island to the mainland. Oyenusi’s robberies were not just crimes; they were symptoms of a larger national fever.

He moved his crew like a businessman running a firm. Targets were scouted, escape routes rehearsed, bribes quietly paid to low-ranking officers. They struck at banks, warehouses, and payroll vans, often wearing stolen military uniforms to delay pursuit. Oyenusi’s command of English and his easy charm allowed him to bluff through checkpoints, and on at least one occasion he walked away from an arrest after convincing a policeman he was on “special government duty.” Every escape inflated the legend; newspapers began treating him like a folk character rather than a fugitive.

But charisma has a half-life. The robberies grew bloodier, the headlines louder. Lagosians began locking themselves indoors at dusk; traders stopped traveling with cash. When the federal government created special anti-robbery squads in early 1971, Oyenusi responded by vanishing into the highways that led toward Ibadan. The story that once made people grin now made them shiver. His smile, once a symbol of daring, had become the face of dread.

When Lagos couldn’t breathe: The City Under Siege (1969–1970)

For almost two years, Lagos lived in what the Daily Times called “the night of perpetual alarm.” Robbers moved like rumor—appearing in Yaba one week, Surulere the next, then vanishing into the traffic and chaos of the mainland. The police were under-equipped, their radios unreliable, their patrol cars few. Streetlights flickered out by midnight, and whole neighborhoods took turns keeping vigil. Oyenusi’s gang understood fear better than any weapon; they used it to paralyze their victims before the first shot.

One night in late 1970, they raided a warehouse at Apapa Wharf, stealing cash meant for dockworkers’ wages. Another week, a payroll van disappeared between Ikeja and Mushin, later found burned, its guards dead. Each incident deepened the myth: that Oyenusi could appear anywhere, that he was protected by spirits, that bullets could not kill him. In truth, he relied on information networks—clerks, drivers, even police informants—who sold him tips for a share of the loot. The city was a maze, and he knew every corner.

Yet Lagos also began to change. The government, embarrassed and under public pressure, imported new weapons and vehicles for the police. A special task force began shadowing suspected hideouts. Radio Lagos aired nightly announcements urging citizens to report strangers. The fear that had once protected Oyenusi was turning against him. He was no longer an invisible legend but a man whose photograph hung in every station house, his grin daring the law to catch him.

Ibadan Screamed: The Expanding Fear Corridor

When Lagos tightened, Oyenusi shifted his operations inland. Ibadan, with its sprawling neighborhoods and slower rhythm, offered both refuge and opportunity. The Lagos–Ibadan Expressway became his artery: at night, trucks and passenger cars vanished along its dark stretches, found later with shattered windscreens and empty cargo. Ibadan residents who had read of Oyenusi in the papers now whispered his name as though he were a ghost crossing city lines.

The police in the Western Region coordinated with their Lagos counterparts, but jurisdictional confusion slowed them down. Oyenusi exploited this divide, moving weapons and cash between the two cities with alarming ease. Some accounts suggest he kept a mistress in Ibadan who handled logistics, though her identity was never confirmed. What mattered was that the fear once contained in Lagos now echoed across Oyo State. People described the sound of gunfire in the night as “Ibadan screaming.”

By mid-1971, the robberies had reached a breaking point. Banks shortened working hours, transport unions hired armed escorts, and newspapers carried daily crime bulletins. The federal military government, led by General Yakubu Gowon, ordered an all-out campaign against armed robbery. That campaign would close the corridor that had sustained Oyenusi’s reign—and set the stage for his capture.

The Betrayal Within: Police Infiltration and the Fall

No criminal empire collapses without betrayal. In Oyenusi’s case, the turning point came from within his own circle. Police records later revealed that one of his lieutenants, arrested during a failed robbery in Mushin, agreed to cooperate in exchange for a reduced sentence. His confession mapped out safe houses across Lagos and Ibadan, revealing where stolen vehicles were repainted and resold. For weeks, detectives trailed leads through motor parks, garages, and cheap hotels until they closed in on a flat in Lagos Island.

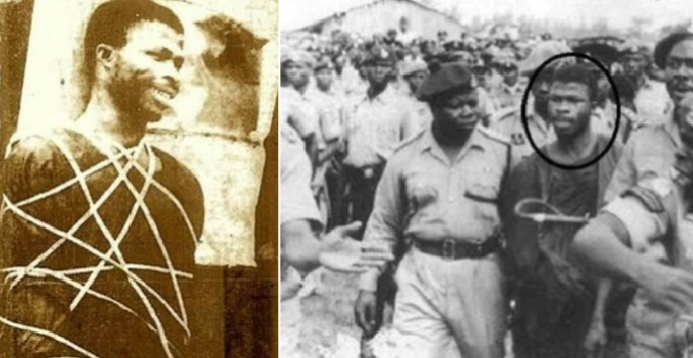

The arrest itself was anticlimactic. Oyenusi, reportedly asleep when officers burst in, reached for a pistol but was overpowered before he could fire. Inside the apartment were stacks of cash, weapons, and several police uniforms. The press soon published photographs of the captured robber, his face still defiant. The myth unraveled fast. Under interrogation, he admitted to “many operations,” including the murder of the doctor whose car he had stolen years earlier. Each confession tightened the noose.

Public anger, stoked by months of fear, demanded an example. The military government announced that Oyenusi and his gang would be tried swiftly by a special tribunal. His trial at the Lagos High Court drew crowds; spectators fought for seats just to see the man whose name had haunted headlines. The verdict was predictable. On September 6, 1971, he and six accomplices were sentenced to death by firing squad. Lagos exhaled—briefly.

Bar Beach Dawn: The Execution That Stopped the Nation

Two days later, the beach became a stage. Soldiers erected wooden stakes, and television crews from the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation set up their cameras. It was one of the first public executions ever televised in Nigeria, meant to shock the nation into obedience. As dawn broke, trucks arrived carrying the condemned men. Oyenusi stepped out last, tall, dressed in a white shirt, still smiling. Witnesses recalled that he greeted the crowd as if arriving for a performance, not an ending.

When the commandant read the sentence, silence fell. A line of soldiers raised their rifles. Oyenusi’s last words, according to Daily Times reporters present, were: “I am dying for the offense I committed.” Then the shots cracked across the beach, echoing over the Atlantic. The crowd gasped, then applauded. For months afterward, Lagosians spoke of that morning as the moment the city awoke from its nightmare. The government promised that armed robbery would never again find room to grow.

Yet the cameras captured more than justice—they captured fascination. In the freeze-frame of his smile, Nigerians saw both villain and warning, glamour and ruin. The man who once terrified two cities had become a mirror for a nation wrestling with its own moral decay.

Echoes of 1971: How Oyenusi’s Death Redefined Fear in Nigeria

The execution did not end robbery; it redefined it. Within a decade, new names—Shina Rambo, Lawrence Anini—would emerge, proving that crime in Nigeria adapts as quickly as the country itself. But Oyenusi’s death changed the psychology of policing and punishment. The public execution, meant to deter, also sensationalized crime. Young men who watched the broadcast later told interviewers they admired his courage even as they feared his fate. In trying to destroy a myth, the state had reinforced it.

For the police, 1971 became a watershed. Specialized anti-robbery units were formalized, intelligence sharing improved, and public tip lines introduced. Lagos slowly regained its nightlife; Ibadan reopened its highways. Yet beneath the surface lingered the same conditions—poverty, unemployment, inequality—that had birthed Oyenusi’s kind. The season of terror ended, but the soil that fed it remained fertile.

Culturally, Oyenusi lived on in rumor, song, and street tales. Parents warned children with his name; filmmakers decades later resurrected his story as moral parable. To historians, he represents the collision of post-colonial chaos and modern criminal enterprise—a figure who understood publicity before Nigeria understood media. His crimes were real, his legend larger.

The Legend and the Lesson: Crime, Charisma, and Consequence

Half a century later, the memory still flickers like an old film reel—the smiling robber, the anxious crowd, the echo of gunfire rolling over Bar Beach. To Lagos, that image marked the end of innocence. The city learned that evil could wear a tailored suit, that courage and cruelty could share the same grin. To Ibadan, it was the echo of a warning: when the metropolis sleeps, its shadow travels.

Oyenusi’s story endures because it touches a deeper chord in Nigeria’s social memory—the tension between ambition and morality, poverty and pride, the hunger to be seen in a country that often looks away. He was a product of his times, but also their distortion: a young man who mistook notoriety for power. The “season of terror” was, in truth, a season of revelation. It showed how quickly order can unravel, how fear can become folklore, and how one man’s defiance can hold two cities hostage.

Today, Bar Beach has long been reclaimed by luxury towers, its sands erased by real estate and tide. But every so often, when Lagos nights grow restless and sirens wail in the distance, the city seems to remember. Somewhere between the waves and the wind, you can almost hear the echo—Lagos breathing again, Ibadan whispering its old scream, and the ghost of Ishola Oyenusi smiling, reminding a nation how close brilliance and ruin can stand.

Closing Reflection

Some presences refuse to fade. Oyenusi is gone, yet the tension he unleashed lingers—felt in the pause before action, in the shadowed corners of streets, in the quiet reckoning of audacity and consequence.

The season of 1971 did not end with gunfire or headlines; it settled into the very rhythm of life, an invisible current beneath the city, shaping how people moved, trusted, and remembered.

Time cannot bury him. Instead, he persists as a dark pulse threading through memory, a reminder that certain moments of terror never truly pass—they linger, shaping the ways we live, decide, and confront the unseen weight of history.