In Nigeria, elections do not always end at the ballot box. Very often, they end under the wooden gavel of judges in crowded courtrooms, far from the noise of polling stations and the chants of campaign rallies.

When citizens queue under the sun to vote, they hope the ballot will settle it all, but for many politicians, the real battle begins after collation.

In the words of some senior lawyers “Elections in Nigeria are never fully decided until the courts have spoken.”

THE ENDLESS PETITIONS

Since 1999, almost every major election in Nigeria has been followed by a flood of petitions.

Some are grounded in real concerns — ballot snatching, voter suppression, or alleged falsification of results. Others are dismissed as “political stunts.”

Candidates file cases alleging non-compliance with the Electoral Act, disputes over party primaries, or the outright disqualification of opponents.

By the time petitions get to the tribunals, weeks of heated campaigns are replaced with piles of legal documents, sworn affidavits, and exhausted witnesses.

THE TRIBUNAL MAZE

To manage these disputes, Nigeria sets up election petition tribunals after every poll.

These panels, often sitting in tense and heavily guarded courtrooms, hear cases from governorship, legislative, and presidential contests.

For National Assembly elections, the Court of Appeal is the final stop. For governorship and presidential polls, the last word rests with the Supreme Court. And in Nigeria’s political dictionary, the court’s verdict is final.

THE HEAVY PRICE TAG

Behind the court battles lies a staggering cost. Candidates reportedly spend billions of naira on legal fees, logistics, and witness mobilisation.

The judiciary itself is stretched thin, with regular cases pushed aside to make way for time-bound election matters.

But the deeper cost is political. States sometimes spend months under uncertainty as their governors fight to retain their seats.

Legislators legislate with one eye on their constituencies and another on court verdicts. In the words of a political analyst, “Litigation paralyses governance, because no one governs effectively when their seat is on trial.”

LESSONS FROM THE PAST

History is littered with rulings that have redrawn Nigeria’s political map.

In 2007, tribunals overturned governorship results in several states.

In 2019, the Imo State governorship judgment that lifted Hope Uzodinma from fourth place to the winner’s seat shocked the nation.

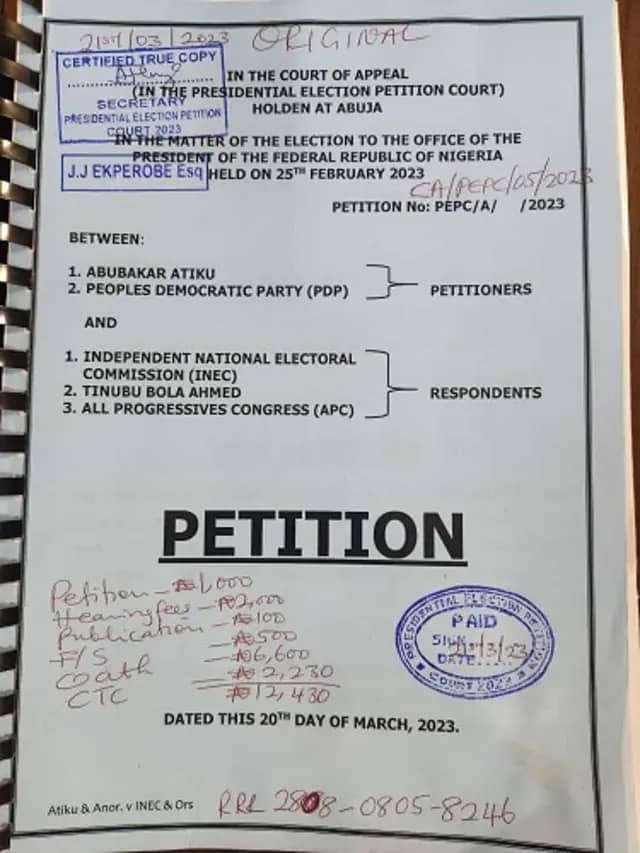

The 2023 presidential election was no different. After months of tension, the Supreme Court upheld Bola Tinubu’s victory against challenges from Atiku Abubakar and Peter Obi.

Once again, the electorate had voted, but the judges had the final say.

DEMOCRACY ON TRIAL

For many Nigerians, this reliance on the courts has become a troubling norm. Critics argue that it erodes faith in elections, since voters increasingly feel their choices will be settled elsewhere.

Supporters, however, insist that tribunals are essential to check fraud and ensure justice.

As constitutional lawyers explained, “the court is a safety valve. Without it, violence would replace litigation. People would rather fight in court than on the streets.”

Still, experts believe reforms are inevitable. They point to solutions such as stronger independence for INEC, stricter internal democracy within political parties, better technology for transparent results, tighter thresholds to discourage frivolous petitions, and swifter timelines to reduce prolonged uncertainty.

These changes, they argue, would ensure that tribunals remain a last resort, not the predictable next step after every election.

BUT WHO REALLY WINS?

For now, Nigeria’s democracy continues to play out both in polling booths and in courtrooms.

Each election cycle reminds citizens that the cost of litigation is not just financial — it is also political and social.

As the country prepares for future polls, one question lingers: can Nigeria build an electoral system where victory is truly decided by the people’s votes, not by judicial pronouncements?

Until then, the gavel and the ballot will continue to share custody of Nigeria’s democracy.