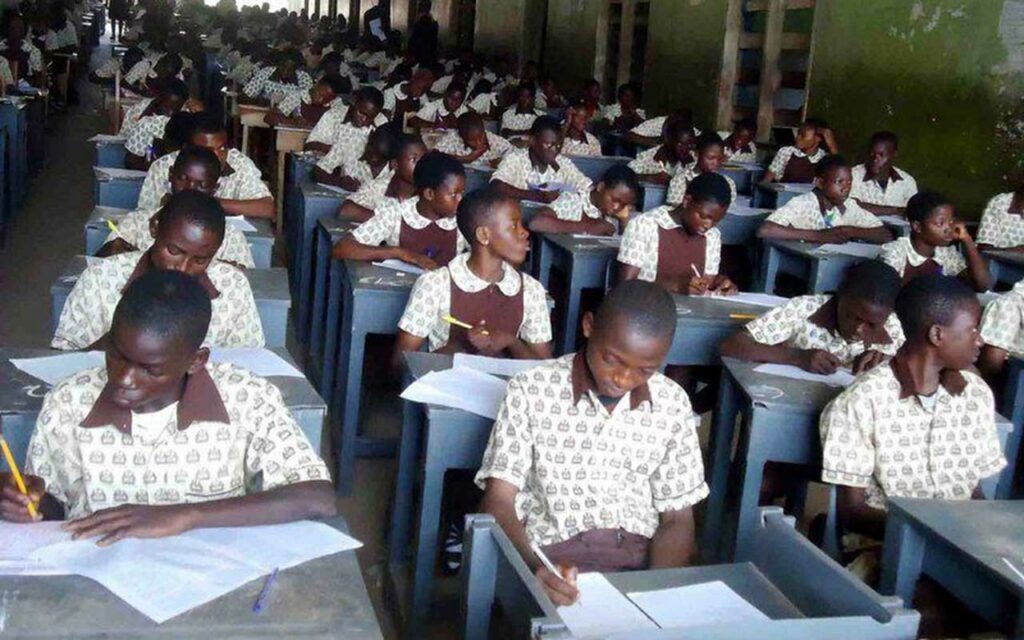

In many parts of Nigeria, a troubling system has quietly grown around secondary school examinations.

Known locally as “miracle centres”, these places are advertised as guaranteed routes to passing the West African Senior School Certificate Examination (WASSCE) and the National Examination Council (NECO) tests.

But they are not usual schools. Instead, they are centres where candidates pay large sums of money in exchange for answers during exams, or where invigilators deliberately look away while malpractice takes place.

The rise of these centres has sparked concerns about the credibility of Nigeria’s education system.

Education experts warn that if nothing is done, the country risks raising a generation of young people whose certificates do not reflect their true knowledge.

“Miracle centres” are often set up in both rural towns and major cities.

They are registered as private schools or coaching centres, but they are not primarily concerned with teaching.

Rather, they focus on arranging exams in a way that guarantees mass success for their candidates.

Investigations by education monitors have shown that candidates are sometimes asked to pay separate fees known as “special packages”.

Once paid, answers are provided to students either before the exam or during the test itself.

In some cases, entire question papers are leaked days before the official exam date.

Teachers who are supposed to supervise often turn into collaborators.

Some sit inside the hall dictating answers to questions while others allow students to use their phones and textbooks.

Why students and parents seek miracle centres

For many students, passing WAEC or NECO is a critical step to securing admission into universities or polytechnics.

However, due to weak preparation, poor teaching standards, and lack of resources, many struggle with these exams.

Parents who fear their children may fail see miracle centres as an easy way out.

For some families, the pressure of societal expectations is a major driver.

When children fail exams repeatedly, parents often face embarrassment within their communities.

This desperation pushes them to embrace any means of securing a pass, even when they know it is wrong.

Miracle centres are not free services. In fact, they have become a thriving business that generates millions of naira every examination season.

In some states, parents pay as little as ₦50,000 while in bigger cities, fees can rise to over ₦200,000.

The money is shared among school owners, teachers, and corrupt exam officials who provide cover for the malpractice.

In some extreme cases, entire local networks are built around the fraud, including cyber operators who run websites that post answers during exams.

The financial gain is one reason the system has continued to grow despite repeated crackdowns.

Technology has made exam malpractice easier in some cases. With smartphones and online groups, students can receive answers in real-time.

Telegram channels and WhatsApp groups are now commonly used to distribute solutions to candidates while they sit inside exam halls.

On the other hand, technology has also helped exam bodies detect and reduce malpractice.

The West African Examinations Council (WAEC) has introduced electronic marking systems and biometric verification to reduce impersonation and multiple entries.

Despite these measures, the fraud continues to adapt and survive.

What WAEC and NECO say

Officials of WAEC and NECO have repeatedly warned against miracle centres.

In a recent statement, WAEC described such centres as “illegal outlets set up only to assist students in cheating”.

The council said it has delisted several schools found guilty of mass cheating and cancelled the results of many candidates.

NECO has also introduced strict supervision and has partnered with security agencies to monitor exam centres.

The registrar of NECO once stated that malpractice is one of the biggest threats to education in Nigeria.

The federal government has made several attempts to tackle exam malpractice.

Laws already exist which prescribe fines and prison terms for offenders.

The Examination Malpractice Act of 1999 provides penalties for candidates, teachers, and officials who engage in fraud.

However, enforcement remains weak.

Very few cases ever make it to court, and even when arrests are made, convictions are rare.

Some education stakeholders argue that without strong enforcement, miracle centres will continue to flourish.

The impact on education and society

The consequences of miracle centres go far beyond the exam hall. When students pass exams without real knowledge, they often struggle in higher institutions.

Lecturers in universities and polytechnics have repeatedly complained that many undergraduates lack basic skills in reading, writing, and problem solving.

Employers also face challenges when graduates with good grades are unable to perform in the workplace.

This trend undermines the value of Nigerian certificates, both locally and internationally.

It also erodes trust in the education system and lowers the motivation of students who study hard.

Voices from teachers and students

Some teachers say they feel pressured by parents to support malpractice. Surprisingly, students themselves often view miracle centres as shortcuts.

For many, the belief is that everyone else is cheating, so it is pointless to remain honest.

This culture has normalised malpractice in many communities.

Educationists argue that parents have the biggest role to play in ending miracle centres.

When families refuse to patronise such places, the market will naturally collapse.

Communities and religious institutions are also encouraged to promote values of honesty and hard work.

Some NGOs have launched campaigns across schools to raise awareness about the dangers of malpractice.

These campaigns stress that while cheating may bring temporary success, it often leads to long-term failure.

Possible solutions

Analysts recommend a combination of strategies to curb miracle centres.

They include improving the quality of teaching in secondary schools, investing in infrastructure, and providing adequate learning materials.

There is also a call for stronger monitoring of exam centres through technology, including the use of CCTV cameras.

Above all, there is demand for strict enforcement of laws, with real consequences for offenders.

Until then, the cycle of malpractice is likely to continue.

As Nigeria continues to battle the challenge of exam malpractice, the future of its education system hangs in the balance.

If the culture of miracle centres persists, the credibility of national certificates will further decline.

But if government, communities, and families work together, it may still be possible to restore integrity to the system.

For now, miracle centres remain a booming industry, fuelled by desperation, profit, and weak enforcement.

And for every exam season that passes, the cost to Nigeria’s education system continues to rise.