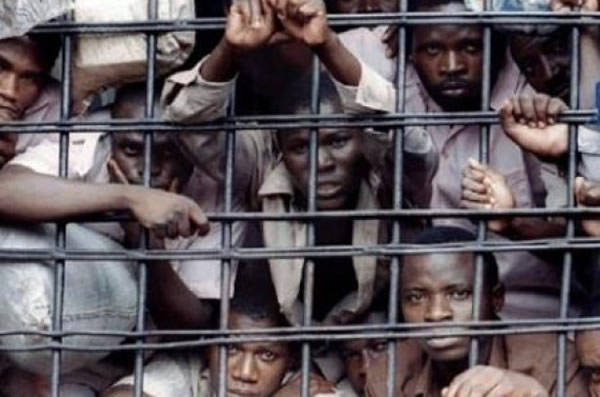

Within Nigeria’s prison walls, thousands of inmates live under constant uncertainty, awaiting trials or serving sentences.

The population includes men, women, and young adults, many of whom are detained for minor offences or prolonged legal delays.

Prisons in Lagos, Kaduna, Port Harcourt, and Abuja are among the most overcrowded, often exceeding their official capacities.

According to the Nigerian Correctional Service, some facilities operate at more than 150 per cent of their intended occupancy.

Awaiting-trial inmates form the majority, highlighting systemic delays in the judicial process that extend incarceration before convictions.

Inside the cells, space is limited, with multiple inmates sharing small rooms designed for far fewer individuals.

Daily routines are dictated by prison officials, but personal survival depends on adaptability and cooperation among inmates.

Food is provided by the facility, though its quantity and quality vary, compelling many inmates to seek supplementary meals.

Visitors, including family members, often bring food and essential items to help sustain those confined.

Some inmates engage in small trades or crafts within the prison to earn additional resources.

Education and skill acquisition programmes exist in select facilities, offering courses in tailoring, carpentry, and literacy.

These programmes aim to prepare inmates for reintegration into society upon release, reducing recidivism.

Healthcare remains a challenge, with overcrowded clinics struggling to manage diseases and injuries common in confined environments.

Infectious diseases, including respiratory infections and skin conditions, spread quickly due to close quarters and inadequate sanitation.

Mental health issues are prevalent, with anxiety, depression, and stress reported among those facing long trials or uncertain futures.

Religious activities, led by chaplains or inmate leaders, provide spiritual support and emotional relief.

Social hierarchies emerge, with older or more experienced inmates offering guidance to newcomers.

Disputes occasionally arise over resources, space, or personal disagreements, and prison officers mediate to prevent escalation.

In some instances, inmates form cooperative arrangements for chores, cooking, and maintaining hygiene.

Women in prisons face additional vulnerabilities, often balancing childcare with confinement or managing unique healthcare needs.

Children living with incarcerated mothers in some facilities are cared for within special arrangements, though space and resources are limited.

Rehabilitation initiatives, supported by non-governmental organisations, include literacy classes, vocational training, and conflict resolution workshops.

These programmes seek to empower inmates with skills and confidence for life after prison.

Despite harsh conditions, stories of solidarity and resilience abound, demonstrating the human capacity to adapt.

Former inmates describe forming friendships, learning trades, and participating in educational programmes as life-changing experiences.

Prison staff, from warders to administrative personnel, play critical roles in maintaining order and ensuring basic human rights are observed.

However, resource limitations, including funding, staffing, and infrastructure, constrain the effectiveness of rehabilitation efforts.

Overcrowding, poor ventilation, and limited sanitation continue to be major challenges affecting health and quality of life.

Legal aid services strive to reduce prolonged pre-trial detention, though the demand often exceeds available support.

Judges, lawyers, and advocacy groups report cases where procedural delays keep individuals incarcerated for months or years.

Despite these challenges, inmates demonstrate agency, creating routines, supporting each other, and seeking education or work opportunities within the confines of the facility.

Visiting family and external support networks remain vital for emotional well-being and mental health.

Reintegration programmes, when available, assist released inmates in finding housing, employment, and social support to prevent repeat offences.

Prisons, while designed to punish or rehabilitate, also reveal societal gaps in justice, infrastructure, and human development.

Through the eyes of inmates, officers, and advocates, the walls tell stories of struggle, resilience, and the quest for dignity.

In the daily battles of Nigerian prisons, survival, adaptation, and hope remain constants for those living behind bars.

As the country continues to reform its correctional system, balancing security, justice, and rehabilitation will be critical for meaningful change.