The night was quiet, but the air was thick with expectation. The lamps that glowed in the prayer hall threw long shadows across the worn floor, as if history itself leaned in to listen. Men and women had gathered not to discuss politics or trade, but to reach for something beyond themselves. Their words rose and fell in unison, the rhythm of their voices carrying both desperation and hope. Outside, the Nigerian night stretched endlessly, dotted with stars. Inside, the atmosphere was alive, trembling with the weight of unspoken dreams. No one present knew it yet, but before the dawn broke, a vision would be planted — one that would reshape not only their community but the landscape of higher education in Nigeria.

It would not be announced with fanfare. No press release captured the moment. What was conceived in that hall was fragile, almost improbable: the idea of a faith-anchored university that would bear the name of a prophet long gone, Joseph Ayo Babalola. The men and women who prayed that night carried more questions than answers.

Could Nigeria, bruised by decades of educational decline, embrace yet another private institution? Could prayer itself sustain the weight of modern academia? They did not know. What they had was a conviction, and sometimes conviction is louder than certainty.

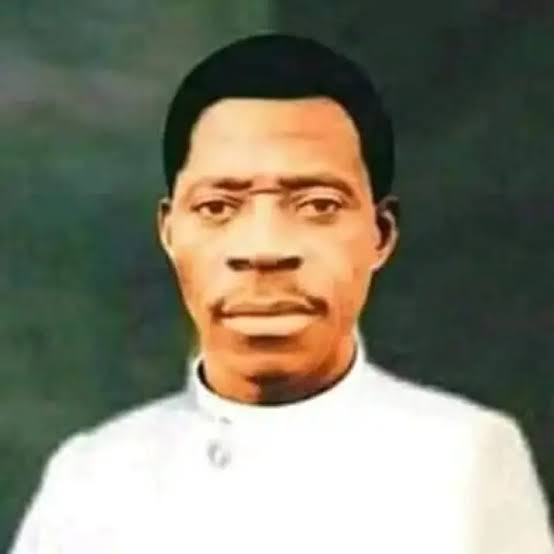

The Spiritual Legacy of Joseph Ayo Babalola

Joseph Ayo Babalola himself had passed away in 1959, decades before the university would come to life. Yet his legacy in Nigeria was monumental. Known as the first General Evangelist of the CAC, his ministry was marked by intense prayer, prophetic authority, and miraculous accounts that drew thousands. For many adherents, his name symbolized uncompromising faith and revival fire.

The town of Ikeji-Arakeji in Osun State, where Babalola’s ministry had taken root, became a kind of spiritual capital. Pilgrims flocked there year after year for conventions and revivals. His burial site became hallowed ground, not in a mystical sense, but as a place where memory and mission intertwined. To name a university after him would be to fuse education with that same spiritual urgency—a daring vision in a country where higher learning was often stripped of moral compass.

Nigeria at the Turn of the Millennium

The prayer meeting that birthed JABU happened against a backdrop of national tension. By the late 1990s and early 2000s, Nigeria’s public universities were collapsing under the weight of prolonged strikes, underfunding, and overcrowding. Students spent more time at home than in lecture halls, waiting for the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) to settle disputes with government. Parents who could afford it began sending their children abroad or to private institutions springing up after the federal government deregulated higher education in 1999.

This deregulation was crucial. For the first time in decades, faith-based organizations and private investors were legally allowed to establish universities. It was an opportunity CAC leaders could not ignore. They asked themselves: if Babalola had once transformed Nigeria’s spiritual landscape with prayer, could his legacy also transform education with prayer?

The Gathering of Burden Bearers

That night, the burden was heavy. Leaders of the CAC, elders, and visionaries converged with a singular ache—the need to birth an institution that would marry spirituality with scholarship. They were not unaware of the enormity of the task. Universities required land, resources, faculty, and above all, accreditation from the National Universities Commission (NUC). But what they carried into that room was not feasibility studies—it was conviction.

Eyewitness accounts describe hours of prayer that felt less like routine intercession and more like labor pains. Groans mingled with declarations, and silence often cut sharper than speech. At intervals, names were invoked—not just of Babalola, but of future generations who would pass through lecture halls yet to be built. Some wept openly, others prayed with clenched fists, as though wrestling down the invisible forces of delay and unbelief.

In those moments, what had been only an idea began to crystallize as an institution. A university—Christian in ethos, entrepreneurial in outlook, rooted in prayer—took shape in the spirit long before its foundation stone would be laid.

Why Prayer Was the Blueprint

In CAC’s worldview, prayer is not an accessory to planning; it is the architecture itself. Every structure must be birthed in intercession before it can be built in reality. For them, skipping that stage would mean raising walls without foundation.

And so, when dawn finally bled into that night of travail, something irreversible had shifted. Those present may not have left with detailed drawings, but they carried a clarity that transcended paperwork: the university must be established, and it must bear the name of Joseph Ayo Babalola.

That night was not simply about academic ambition. It was about reclaiming education as a spiritual mandate. It was about telling a generation lost to strikes, cultism, and moral drift that there could be a different kind of university—one where prayer and pedagogy coexisted, one where the sacred was not divorced from the scholarly.

The vigil ended with exhausted bodies but quickened spirits. Unknown to them, Nigeria’s educational landscape was about to gain a new chapter. And history would forever remember that its first page was written not with ink but with whispered prayers under the dim light of Ikeji-Arakeji.

The Founding Struggles

The path from prayer to reality was anything but smooth. Establishing a private university in Nigeria required meeting the demanding standards of the National Universities Commission (NUC). The CAC leadership had to submit detailed academic briefs, financial roadmaps, and physical plans. Inspectors scrutinized everything: land size, library holdings, staff qualifications, and curriculum outlines.

Funding was the most immediate challenge. Unlike governments with deep coffers, the church depended on donations, pledges, and sacrificial giving. Congregants were called upon to see their tithes and offerings not just as charity but as investments in the future of Nigerian youth. Land was secured in Ikeji-Arakeji, Osun State — the same soil where Babalola’s ministry had once flourished.

The building process was slow. Bricks rose under the heat of the sun, classrooms were carved out of red earth, and each milestone felt like a miracle. Skeptics predicted failure. Nigeria’s economy was unstable, corruption rampant, and higher education itself a battlefield. But the leadership pressed on, fueled by the memory of that prayerful night.

By 2004, their persistence bore fruit. The NUC granted approval, and Joseph Ayo Babalola University was formally licensed as Nigeria’s first entrepreneurial university. It was a milestone not only for the CAC but for Nigeria’s educational landscape.

The First Buildings

With the license secured, construction intensified. Ikeji-Arakeji transformed into a campus: lecture theatres rising from red earth, hostels standing in clusters, a chapel overlooking the grounds. The campus bore the feel of both modernity and spirituality—functional enough for academic pursuit, sacred enough for its identity.

The founding architects insisted that no building would be dedicated without prayer. Each block was not just commissioned with ribbon-cutting but also with intercession. The soil itself was saturated with the memory of vigil nights, as though every stone carried both physical and spiritual weight.

Recruiting the First Staff

No university exists without staff, and here lay another hurdle. Recruiting qualified lecturers to a rural town in Osun was no easy task. Many academics preferred urban centers with better infrastructure. To lure them to Ikeji-Arakeji required persuasion, incentives, and the appeal of vision.

Some joined out of faith, believing in the uniqueness of a prayer-based university. Others came out of necessity, seeking stable employment. Slowly, a faculty was assembled—scientists, lawyers, managers, agriculturalists, each one part of the pioneering corps that would set the tone for JABU’s academic culture.

The First Students

In January 2006, the university admitted its pioneer students. They walked into a campus that still smelled of fresh cement, where lawns were just beginning to take shape and lecture timetables were often adjusted on the fly. For the students, it was both thrilling and unsettling. They were guinea pigs, stepping into an institution without alumni, without established traditions, without certainty of recognition.

Yet, the pioneering spirit carried its own rewards. Faculty members were deeply invested, often taking on roles beyond teaching — mentoring, guiding, shaping. Students found themselves not only studying engineering, law, and management but also absorbing the ethos of discipline and prayer that infused the institution. Morning devotions, campus fellowships, and strict codes of conduct made JABU distinct from its secular counterparts.

For these students, being part of the first generation meant writing history with their presence. Every graduation ceremony, every accolade, every expansion project was theirs to claim. They were not simply beneficiaries of prayer but proof that what was conceived in prayer could stand in reality.

Gatherings That Keep the Vision Alive

Time has tested the strength of Joseph Ayo Babalola University’s foundation, and each gathering on its campus now feels like a continuation of the night when it was first conceived in prayer. The convocation ceremonies, for instance, are more than mere graduations. They are annual reminders that what began as whispered petitions in a hall has become living proof in the lives of students. In December 2024, when the 15th convocation filled the air with songs, robes, and prayers of thanksgiving, the spectacle felt less like a formal rite of passage and more like a harvest festival. Out of more than six hundred graduating students, fifty walked away as first-class scholars. The best graduating student, a young woman named Mary Omachi from the Department of Mass Communication, carried a perfect story on her shoulders — her 4.88 CGPA standing as a beacon of what can happen when conviction meets discipline.

Beyond convocation grounds, JABU’s legacy rippled outward into professional spaces. At the Nigerian Law School, three of its law graduates returned home with first-class honours, proof that the prayers which built lecture halls could also sustain brilliance in the nation’s most competitive legal corridors. One of them, Janet Adio, did not only excel but rose to the top of her specialization, claiming recognition as the best female student in Criminal Litigation. These moments became symbols that JABU was not just surviving; it was quietly re-drawing the map of expectations for private universities in Nigeria.

The rhythm of gatherings on campus has also shifted into intellectual festivals. In October 2023, the College of Management Sciences hosted an international conference on “Managing Risk for Sustainable Development in a Digital Economy.” At the General Adebayo Lecture Theatre, scholars debated fintech, entrepreneurship, and the future of digital risk management. For an institution born in prayer, such conversations represented a bold step into the technological questions of the twenty-first century. The conference was not an escape from its spiritual identity but rather its extension — a way of asking what faith and prayer might look like in an age of algorithms and digital currencies.

Even in regulatory halls, JABU’s name has continued to resonate. In 2025, new programmes won accreditation from the National Universities Commission, widening the school’s horizon. Each approval felt like another answered prayer, another confirmation that the soil where Babalola once prayed could still yield futures for generations yet unborn.

What began on a night when men and women bent their knees has grown into decades of classrooms, convocations, conferences, and careers. Each gathering at JABU — whether students in robes celebrating graduation, lawyers taking oaths after excelling at the Bar Finals, or academics trading ideas under the soft glow of lecture hall lights — becomes a verse in the same unending prayer. The university does not merely exist as buildings on Osun soil; it exists as an unfolding story, proof that education can be born in devotion and sustained by perseverance.

The Legacy of Prayer in Academia

The legacy of Joseph Ayo Babalola University rests on a paradox. It is both an institution of higher learning, bound by accreditation and rankings, and a monument of faith, rooted in prayer and spirituality. This dual identity sets it apart in Nigeria’s educational ecosystem.

To some, the emphasis on prayer in academia feels out of place, even antiquated. To others, it is precisely what the nation needs — a moral compass in a system where corruption and compromise have become normalized. JABU’s continued survival over two decades testifies to the enduring power of its founding vision.

Graduates of the university have gone on to careers in business, law, engineering, and ministry. Many carry with them not just academic credentials but the memory of a university where learning was inseparable from devotion. The name Babalola still echoes in chapel services, in convocations, in the stories told to each new cohort of students.

In this way, JABU is not only a university but also a sermon — a living argument that faith can shape education, that prayer can be as foundational as policy, and that memory can fuel innovation.

Final Reflection: A Living Prayer Unfolding

What really happened that night? On the surface, it was simply a prayer meeting. But in hindsight, it was the spark that lit the fire of an enduring institution. From that moment of spiritual clarity emerged a university that has weathered Nigeria’s storms and carved out a place for itself among the country’s private institutions.

The story of JABU is not a story of perfection. It is a story of persistence — of leaders who dared to imagine a university in prayer, of congregants who gave sacrificially, of students who believed enough to enroll, and of a legacy that continues to evolve.

As Nigeria’s higher education system faces new challenges in the age of technology and globalization, the night of prayer remains a reminder. That education, when rooted in conviction, can transcend the ordinary. That the memory of a prophet can inspire classrooms. That universities, too, can be conceived not just in policy papers but in the silence of prayer.

And so JABU stands — not merely as a campus in Osun State but as a living prayer still unfolding, line by line, life by life.