The drums started before sunrise. From the lower hills of Bere to the winding roads of Beere, Ibadan was awake — restless, half proud, half perplexed. That morning, Mapo Hall gleamed under the August sun like an ancestral witness dressed for judgment. Red carpets rolled over ancient stones; banners flapped in the wind, announcing the “Installation of 21 New Obas in Ibadanland.” The city that once wore one crown now prepared to host twenty-two.

But the most important seat in the hall — the Olubadan’s seat — was empty.

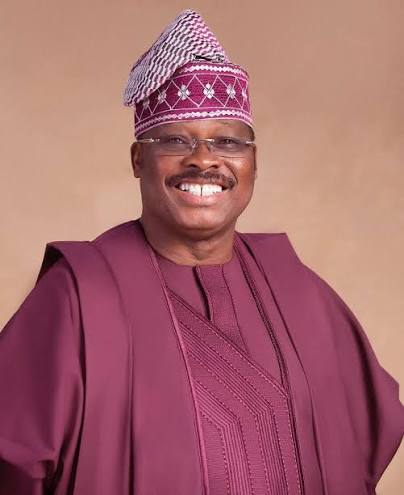

As the Oyo State Governor, Abiola Ajimobi, arrived with his entourage, the crowd stood. Cameras clicked, horses neighed, and the sound of bata drums clashed with modern microphones. Ajimobi smiled — a politician’s smile, half charisma, half defiance. His agbada shimmered gold, the color of power, and his red cap tilted slightly forward like a signal of intent.

He wasn’t just attending history. He was rewriting it.

At that moment, Ibadan stood suspended between two worlds — the world of ancient hierarchy and the world of state ambition. The governor had come to crown kings. The Olubadan had chosen to stay in his palace.

In Yoruba cosmology, absence can be louder than presence. The Olubadan’s silence that day became the city’s echo for years to come.

The City of Crowns: Ibadan’s Fragile Order

Long before the British drew borders or governors wore agbadas, Ibadan was a warrior city — a refuge for broken empires and exiled princes. Founded in the early 19th century after the fall of the old Oyo Empire, the city was less a kingdom than a coalition of warlords. Its rulers were not born into power; they ascended through courage, strategy, and seniority.

Ibadan’s monarchy was built on meritocracy, not royal blood. The Olubadan’s stool was the city’s social ladder — a long, deliberate climb through the ranks of Mogaji, Jagun, Balogun, Otun, until the crown rested on the head of the most senior high chief. It could take decades. But every chief knew his place in the queue. There were no shortcuts. No rival thrones.

That structure was Ibadan’s pride — a rare blend of democracy within monarchy. One king. Two lines of succession. No confusion.

To be Olubadan was not to be the richest or loudest. It was to be the city’s moral compass, the keeper of ancestral discipline. For generations, Ibadan’s stability came from that sacred simplicity — one city, one king, one voice.

Then came the governor who believed tradition could be “upgraded.”

The Governor Who Wanted to Reform a Kingdom

Abiola Ajimobi had always seen himself as more than a politician. Before politics, he was a technocrat — managing director at National Oil and Chemical Marketing Company, a man who admired structure, systems, and reform. When he became Oyo State’s first two-term governor in 2011, he carried that corporate instinct into governance. Efficiency mattered to him. So did legacy.

By 2016, Ajimobi had begun to see Ibadan’s chieftaincy system as outdated — an old structure too rigid for modern realities. High chiefs who had served the city for decades often died before ascending the throne. The system, in his view, needed renewal.

In March 2017, a judicial panel headed by retired Justice Akintunde Boade was inaugurated to review the 1957 Ibadan Chieftaincy Declaration. The recommendations were bold: recognize 21 high chiefs and baales as Obas — each with his own beaded crown, each retaining allegiance to the Olubadan. The governor approved it.

To Ajimobi, this was modernization. To Ibadan’s traditionalists, it was sacrilege.

He wanted to create a network of crowned sub-monarchs who could represent development interests across Ibadanland. It was, politically, an efficient way to decentralize loyalty and consolidate influence. But culturally, it struck at the heart of Ibadan’s delicate hierarchy.

No one dared to multiply crowns in a city where the number had always been one.

The Olubadan’s Refusal

At Popoyemoja Palace, the Olubadan, Oba Saliu Adetunji, sat quietly in his armchair that August morning, refusing to attend the coronation. He had reigned barely a year, yet his sense of guardianship over tradition was unwavering.

For the aged monarch, the governor’s decision was not reform — it was rebellion. To multiply crowns was to scatter heritage. To share authority was to diminish it. The Olubadan believed that history was being altered without the consent of its custodians.

As the crowd gathered at Mapo, Oba Saliu remained in his palace, surrounded by chiefs loyal to him, their expressions somber. Outside, his subjects debated. Some called him stubborn; others called him noble. But he never raised his voice. He didn’t need to. His silence was both protest and prophecy.

When the ceremony ended, the governor declared that “Ibadan will never remain the same again.” The Olubadan, in private, replied that “Ibadan will always remain what it has been — one king, one throne.”

The Coronation at Mapo Hall

Mapo Hall that day resembled an open theatre of Yoruba destiny. One by one, 21 high chiefs and baales stepped forward, dressed in new royal robes, as the governor handed them their staff of office. The air smelled of power and perfume; the drums beat with uneasy excitement.

Photographs captured the moment — Ajimobi standing tall among kings, smiling, his expression suggesting victory. Behind him, the new Obas adjusted their beaded crowns awkwardly, as if aware that they were wearing a controversy, not a coronation.

The symbolism was heavy.

A governor — an elected official — had become the maker of kings.

To his supporters, Ajimobi’s move was visionary: a bridge between ancient authority and modern administration. To critics, it was an assault on Ibadan’s identity — the governor had worn the language of tradition to serve the machinery of politics.

The absence of the Olubadan at the event became its most striking headline. The seat reserved for him stood untouched throughout the ceremony, like a ghost of the old order watching the new one emerge.

The Aftermath: Lawsuits and Loyalties

In the months that followed, Ibadan became a city of parallel crowns.

The Olubadan filed a case at the Oyo State High Court, challenging the validity of the 21 coronations. The legal argument was clear: only the Olubadan, not the governor, could preside over the elevation of traditional chiefs. The court battle turned the city into an ideological arena — tradition versus governance, palace versus government house.

Within the Olubadan-in-Council, old alliances fractured. Some chiefs who accepted Ajimobi’s crowns became alienated from the palace. Meetings grew tense; greetings turned formal. The Olubadan, though calm, was deeply wounded.

Public opinion split along generational lines. The older citizens saw Ajimobi’s act as arrogance — a governor playing god over heritage. Younger Ibadan residents, more urban-minded, admired his audacity. “He modernized tradition,” they said.

But beneath those arguments lay an older wound — the Yoruba struggle between lineage and leadership.

The Courts Speak, But the City Remembers

In 2019, shortly before Ajimobi’s exit from office, the court declared the coronation of the 21 Obas illegal, nullifying the 2017 chieftaincy review. Governor Seyi Makinde, who succeeded Ajimobi, restored the old order. The Olubadan’s sole authority was reaffirmed.

Yet, history does not forget rebellion.

Even after Ajimobi’s passing in 2020, the debate persisted — was he a reformer misunderstood by tradition, or a politician who misunderstood tradition? In Ibadan’s oral memory, both truths coexist.

The Olubadan himself would later join the ancestors in 2022, leaving behind not just a throne, but a lesson in restraint. He never retaliated; he simply waited — and time itself vindicated him.

Between Legacy and Loss

In Yoruba cosmology, power is never singular. It is shared between the seen and the unseen. Ajimobi’s crown for 21 Obas became both his achievement and his burden.

For years, his political admirers remembered him as the first governor bold enough to confront tradition. His critics remembered him as the first to politicize it so deeply. Both perspectives hold fragments of truth.

The rift reshaped Ibadan’s identity. It forced a city proud of its unity to question its own hierarchy. It exposed the fragile line between modernization and desecration — between administrative governance and ancestral authority.

When Ajimobi died during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, tributes poured in across the country. But in Ibadan, people remembered the Mapo Hall day — not out of bitterness, but as a moment when history blinked.

Reflections: Crowns, Power, and the Price of Change

The Ajimobi–Olubadan conflict remains one of the most symbolic clashes between democracy and monarchy in modern Yoruba history. It was never just about crowns; it was about control — who defines identity in a city where tradition predates the state.

Ibadan’s story shows that modernization without consent becomes alienation. Tradition without flexibility becomes fossilized. The balance is delicate — and both Ajimobi and the Olubadan, in their contrasting ways, exposed how fragile that balance can be.

Today, as Ibadan continues to grow — its skyline dotted with new estates and malls — Mapo Hall still stands, carrying echoes of 2017. The red carpet has faded, the drums are silent, but the question remains:

Who owns Ibadan’s crown — the government that rules, or the tradition that endures? In the end, power was transient. The crowns remain.