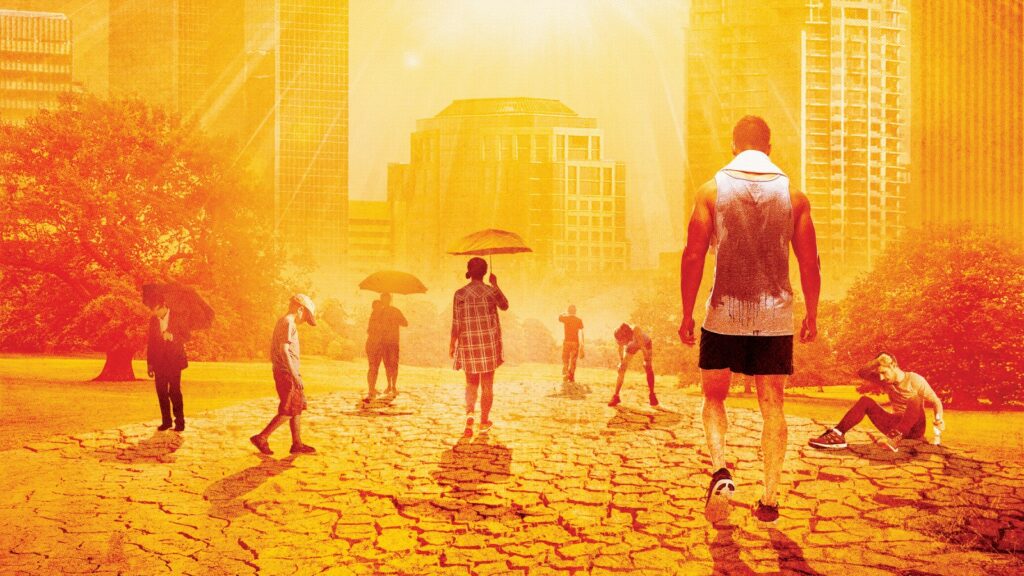

Across Nigerian cities, rising temperatures have become one of the most noticeable signs of a changing climate.

Each year, the air grows thicker, nights feel warmer, and daytime heat lasts longer than before.

What used to be short dry spells are now prolonged periods of intense heat that stretch across seasons.

From Lagos to Kano, residents are adjusting to the reality of a hotter environment that disrupts daily life and work.

Experts attribute the rise in temperature to rapid urbanisation, deforestation, and increased human activity.

Concrete roads, industrial zones, and high-rise buildings have replaced trees, wetlands, and open spaces that once absorbed heat.

The result is what scientists call the “urban heat island effect”, where cities trap heat and stay warmer than surrounding areas.

In places like Abuja and Port Harcourt, air conditioners and generators now run longer, driving up energy consumption and emissions.

The pattern creates a loop where the very actions taken to stay cool worsen the overall heat.

Roadside traders, commuters, and construction workers are among the most affected by this constant exposure.

Many spend hours in direct sunlight, risking dehydration, heat exhaustion, and other health problems.

Hospitals report seasonal spikes in heat-related illnesses, especially among children, the elderly, and outdoor workers.

In crowded areas with poor housing and limited ventilation, the situation is even more severe.

Metal roofs, narrow streets, and congested homes trap warm air, turning entire neighbourhoods into heat pockets.

The growing population of urban dwellers makes it difficult to maintain green zones and open parks.

As buildings rise, trees fall, and the natural balance that cools the environment continues to disappear.

Flooding and pollution add to the problem, reducing the capacity of soil and water bodies to regulate temperature.

Rivers that once served as cooling buffers are now clogged with waste, reducing air flow and evaporation.

Environmentalists argue that the heat wave crisis is not just about weather, but about poor urban planning.

Without coordinated action, Nigerian cities risk becoming unlivable during certain months of the year.

Planting more trees, redesigning roads, and promoting energy-efficient buildings are seen as key solutions.

Some state governments have begun urban greening programmes, but progress remains slow.

Urban farmers and community groups are also experimenting with rooftop gardens and shaded walkways.

While these efforts show promise, the scale of the problem demands stronger policies and consistent enforcement.

Experts stress the need for environmental education and public awareness about how daily habits influence heat.

Simple actions such as reducing waste burning, using reflective roofing, and preserving local vegetation can make a difference.

In schools and workplaces, heat safety measures are being introduced to prevent exposure and improve comfort.

As global temperatures continue to rise, Nigeria’s cities stand at the frontline of the challenge.

The question is whether communities, policymakers, and citizens can adapt fast enough to slow the warming trend.

Until that happens, the heat will remain more than a seasonal discomfort—it will be a warning of what lies ahead.