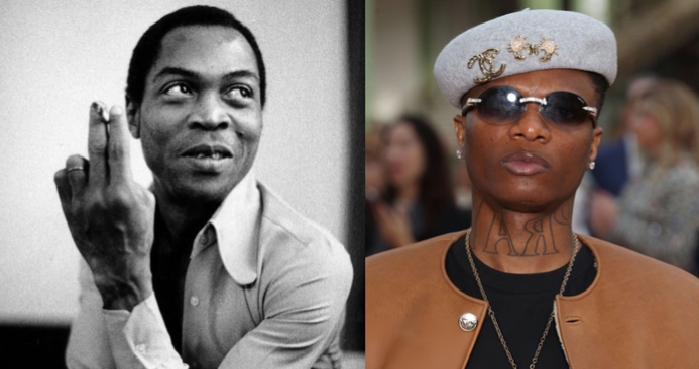

For weeks, the argument lay dormant, not because it lacked substance, but because no one had bothered to count carefully. Names were invoked loosely, legacies were stretched thin, and influence was spoken of in broad emotional strokes rather than measurable facts. Then a clash erupted, not between two musicians trading melodies, but between two ideas of what Fela Kuti represents in modern Nigerian culture.

The Wizkid and Seun Kuti dispute did not begin with a song or a stage performance, it began with comparisons. Comparisons repeated so often by fans that they hardened into assumptions. Wizkid as a successor, Wizkid as an inheritor, Wizkid as a modern Fela? What followed was not outrage, but resistance, firm, deliberate, and rooted in history.

To understand why the reaction was so sharp, one must step away from sentiment and return to record keeping. How many times did Wizkid actually touch Fela Kuti’s music? When did it happen, what was taken, what was transformed, and what was left behind? This is not a story about disrespect or homage alone, it is a story about chronology, intent, and the quiet power of repetition.

The answer, when laid out plainly, reveals more than numbers, it reveals a pattern.

The First Reference and the Sound of Inheritance in 2012

Wizkid’s earliest known engagement with Fela Kuti’s work surfaced in 2012, long before global awards and stadium tours reframed his public image. The Zombie freestyle was not a commercial release, nor was it framed as a manifesto, it was casual, light, and situated within a moment when Nigerian pop artists freely borrowed cultural symbols without scrutiny.

The original Zombie by Fela Kuti was confrontational by design, it mocked military obedience and authoritarian control at a time when such defiance carried real physical danger. Wizkid’s freestyle, by contrast, stripped the title of its political weight, repurposing it as a recognizable hook within a youthful, carefree expression. The reference was obvious, yet the intention was different.

This first moment matters because it establishes tone. Wizkid did not approach Fela as an ideological figure, he approached him as a sonic ancestor. The borrowing was aesthetic rather than philosophical, rhythm rather than rebellion, and that distinction would resurface repeatedly.

At the time, the moment passed quietly. No debates followed, no gatekeepers emerged, it was simply another example of how Fela’s catalog continued to echo through Nigerian music without friction.

Jaiye Jaiye and the Year Influence Became Visible in 2013

By 2013, the relationship between Wizkid and Fela’s musical lineage had shifted from casual reference to deliberate collaboration. Jaiye Jaiye was not just a song, it was a signal. Featuring Femi Kuti, Fela’s eldest son, the track positioned itself within Afrobeat history while remaining firmly rooted in contemporary pop structure.

The sample from Lady was unmistakable, and unlike earlier references, it was intentional, cleared, and celebrated. This was Wizkid acknowledging lineage openly rather than borrowing quietly. The presence of Femi Kuti complicated the narrative, as it suggested approval rather than appropriation.

Yet even here, the separation remained clear. Fela’s Lady was a social critique layered with irony and confrontation, Jaiye Jaiye was aspirational, reflective, and inward looking, it spoke of personal survival rather than collective resistance.

This moment marked a turning point. Wizkid was no longer merely referencing Fela’s sound, he was standing beside the legacy, close enough to touch it, but not close enough to inherit its political burden, and that choice would define much of what followed.

Wonder and the Shift Toward Sonic Memory in 2014

In 2014, Wizkid released Wonder, a track that leaned further into atmosphere than message. Sampling Just Like That, the song demonstrated how Fela’s later work could be repurposed purely as texture. The reference was subtle, almost hidden beneath layers of modern production.

This was not homage in the traditional sense, it was memory, the kind of memory that lingers in rhythm rather than lyrics. For listeners unfamiliar with Fela’s catalog, the connection passed unnoticed, for those who knew, it registered as a quiet nod rather than a declaration.

Here, Wizkid refined his approach. He was no longer pointing at Fela, he was weaving him into the fabric. This approach allowed influence to exist without demanding interpretation, and it reinforced the idea that Wizkid’s engagement with Fela was selective, not comprehensive.

By this point, a pattern had formed. Fela was being sampled as sound, not as stance.

Expensive Shit and the Reframing of Meaning in 2015

When Wizkid released Expensive Shit in 2015, the conversation shifted. Unlike previous tracks, the borrowing here was conceptual as well as nominal. The original Fela song was rooted in absurdity and resistance, using humor to critique power structures and state control.

Wizkid’s version transformed the phrase entirely. What once symbolized defiance became shorthand for luxury and excess. The irony was not accidental, it reflected a generational change in values, from survival to success, from protest to pleasure.

This was the moment where critics later began to draw lines. The same words, two radically different worlds, one born in confrontation, the other in consumption, neither invalid, but undeniably distant.

At the time of release, the shift was celebrated, not questioned, it would only become controversial years later, when legacy itself became contested terrain.

Sweet Love and the Romanticization of Afrobeat in 2017

Sweet Love marked another evolution. Sampling Shakara, the track softened Afrobeat into romance. Gone were the sharp edges, in their place were warmth, intimacy, and emotional accessibility. The transformation was complete.

This was Afrobeat as mood rather than movement, as something to feel rather than something to fight with. Wizkid had mastered the art of extracting melody while leaving message untouched.

By now, the pattern was undeniable. Each interaction with Fela’s work moved further away from confrontation and closer to personal expression. This was not erasure, it was reinterpretation through distance.

For many listeners, this approach felt respectful, for others, it felt incomplete, and the divide widened quietly.

Joro and the Return to Zombie in 2019

Joro’s release in 2019 closed the loop. Once again, Wizkid returned to Zombie, not as protest, but as chant. The motifs were there, the echoes unmistakable, yet the meaning had fully shifted into dance culture.

This was Afrobeat reimagined as global currency, portable, rhythmic, and detached from its original political weight. It was also Wizkid’s most internationally visible engagement with Fela’s legacy.

By this point, the cumulative count stood at six. Six moments across seven years, not one, not two, a recurring relationship.

The Politics of Sound: When Influence Meets Ideology

Wizkid’s engagement with Fela Kuti’s music cannot be separated from the ideological weight Fela carried. Fela did not create Afrobeat to entertain only, he created it to challenge, to question authority, to disrupt complacency. When modern artists sample or reference his work, the conversation is not just musical, it is ethical, political, and cultural. Does borrowing a rhythm carry responsibility, or is it purely creative?

Each of Wizkid’s six references highlights a tension between sound and meaning. Some are playful, some are aesthetic, and some engage directly with Fela’s sonic signatures. None fully embrace Fela’s political mission. That gap, however, is precisely what sparked Seun Kuti’s critique.

This is not a simple issue of rights or homage. It is about lineage, about how a culture negotiates continuity and transformation. How does one honor a legacy without replicating the exact message? How does influence differ from inheritance?

In modern Afrobeats, influence is inevitable. Every artist is standing on the shoulders of giants. Yet the giants’ shadows remain, sometimes long, sometimes faint, reminding listeners that context matters as much as melody.

Sampling Versus Interpretation: Understanding the Distinctions

Many fans assume that sampling is straightforward: take a song, use it, and the intent is clear. In reality, there is a spectrum from direct sampling to loose reference to thematic inspiration. Wizkid’s work falls across this spectrum. “Jaiye Jaiye” is a direct homage with Femi Kuti’s blessing, while “Wonder” or “Sweet Love” is an interpretive borrowing, more about feeling than message.

Interpretation allows for creativity, yet it invites scrutiny. Seun Kuti’s position highlights this tension. When does interpretation become misrepresentation? When does sampling risk detaching a work from its original meaning?

The line between influence and appropriation is always contested, especially with figures like Fela Kuti. Fela’s music was deeply tied to context, social critique, and activism. Extracting rhythm or motif without engaging the message transforms the music’s cultural role.

Wizkid’s track record shows repeated engagement over years, yet the approach is consistent: aesthetic adoption rather than political immersion. The consistency makes the pattern visible, and for observers, it frames the debate not as accidental, but as deliberate creative choice.

Generational Perspectives: Fela Then, Wizkid Now

Fela Kuti lived in a world where music was a weapon, where notes carried the risk of imprisonment, and where every song was a conversation with the state. For contemporary artists like Wizkid, global success, branding, and digital influence are paramount. The generational gap frames the misunderstanding between Seun and Wizkid.

One generation measures impact in protest and ideology, the other in streams, tours, and collaborations. Does modernity excuse detachment from the original message, or does it require reinterpretation that remains faithful to the source?

Fans often compound the tension, praising artists for recognition of Fela without analyzing the depth of engagement. The result is public discourse shaped by perception rather than precision, creating friction between those who value ideology and those who value aesthetics.

This gap is critical for understanding the Wizkid-Seun debate. It is not a personal feud but a collision of historical consciousness and contemporary creativity, where interpretation becomes the site of negotiation over meaning and legacy.

Why Seun Kuti Pushed Back

Seun Kuti’s response did not emerge from nowhere. It emerged from accumulation, from watching his father’s work be celebrated sonically while stripped ideologically. His argument was not about permission, but about precision.

To Seun, Fela was not a genre, he was a confrontation. Comparing global success to revolutionary impact felt like dilution rather than tribute.

Wizkid’s response, sharp and personal, revealed the gap between intention and interpretation. What one side saw as homage, the other saw as reduction.

What the Count Actually Tells Us

Six references, seven years, a clear pattern of aesthetic borrowing without ideological adoption.This is not theft, it is not disrespect, it is transformation.

The real conflict is not about sampling, it is about meaning.