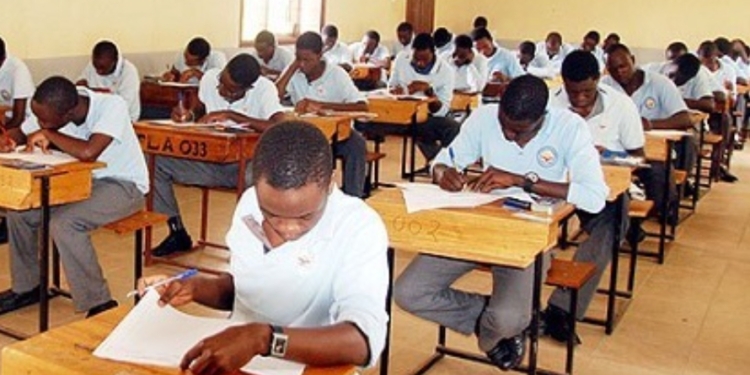

A Nigerian undergraduate recalled writing the Senior School Certificate Examination ten different times because he could not secure a credit pass in mathematics.

The federal government, through the ministry of education, later announced that mathematics would no longer be compulsory for admission into arts and humanities programmes.

The policy immediately divided opinions nationwide as many Nigerians questioned whether the move would truly widen access or damage standards.

The decision was explained as a strategy to expand tertiary access and reduce the number of students shut out by mathematics.

The minister of education, Tunji Alausa, said the aim was to democratise entry into higher institutions and give more young Nigerians opportunity.

He explained that millions sit for admission tests annually but only a fraction gain entry and insisted that “outdated barriers” needed review.

However, critics argued that removing mathematics as a compulsory credit for admission could discourage seriousness and weaken national numeracy capacity.

The federal government later clarified that mathematics remains compulsory at SSCE level but arts candidates would no longer require a credit pass to gain admission.

Several education analysts warned that the policy could make students comfortable with avoiding mathematics completely.

The head of department of mathematics, University of Lagos, Israel Abiala, said the policy appeared poorly thought out.

He said, “While the world is gearing towards STEM, Nigeria is removing the ‘M’, which is mathematics, for its students.”

He argued that the real solution was to improve teaching methods, motivate interest and strengthen support systems for struggling pupils.

He suggested using visual learning, practical tools and better teaching resources to make mathematics less abstract and more understandable.

Another mathematics expert, Sokenu Samuel of International School, UNILAG, said many arts students would simply abandon mathematics under the new policy.

He insisted that mathematics was not inherently difficult but often poorly taught, while some students lacked discipline or interest.

He said the policy should either be reversed or reviewed to still insist on a minimum pass requirement.

A professor of developmental psychology, Gbenu Akinwale, warned that the policy could produce graduates lacking essential numeracy skills.

She said employers increasingly test candidates using quantitative and analytical assessments and many students may struggle in the future.

She added that mathematics remains vital to reasoning, problem-solving and real-life decision-making beyond classroom theory.

Several students also shared emotional experiences of repeatedly failing mathematics examinations and being denied admission for years.

Some eventually secured credits after multiple attempts while others felt the subject had unfairly limited their future.

Beyond emotions, data show that Nigeria’s admission crisis also relates to limited institutional capacity rather than mathematics alone.

Reports revealed that hundreds of thousands of applicants seek limited university spaces yearly, leaving many qualified candidates excluded.

Analysts believe the policy debate should focus on expanding university capacity, improving infrastructure and strengthening teaching quality.

Comparisons from other countries show that many nations still maintain mathematics as a strong educational foundation.

In the United States, the United Kingdom and China, mathematics remains central, though with flexible pathways in some cases.

A human resource expert, Yomi Fawehinmi, warned that Nigeria already has weak numeracy levels and cannot afford further decline.

He said, “We are shooting ourselves in the foot because our numeracy skills are already very low as the data shows.”

He also questioned whether the minister had the legal authority to unilaterally change admission requirements.

As conversations continue, stakeholders insist that access, standards and national development must be balanced carefully.

Discussion about this post