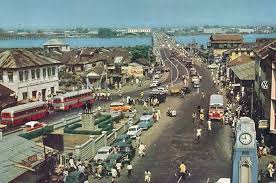

Lagos in the mid-1960s hummed with a restless energy. The streets were crowded, the motor horns relentless, and the air thick with rumors that traveled faster than the truth. Politicians spoke in careful whispers, while the city’s cafés and beer parlors buzzed with speculation—who would rise, who would fall, and who might betray whom next.

On the surface, Nigeria’s First Republic stood as a symbol of independence and democracy. But beneath the veneer of progress, tension simmered. Alliances were fragile, loyalties uncertain, and every decision made in Parliament seemed to echo with danger.

Something was coming, and Lagos could feel it. The city had become a stage for forces far beyond its control—forces of ambition, suspicion, and unrest—that soon shaped the nation’s destiny in ways no one could have predicted.

This is the story of Lagos at the edge: a city witnessing the slow, inevitable collapse of the First Republic.

Lagos, Capital of a Dream

When Nigeria gained independence on October 1, 1960, Lagos glittered with promise. Union Jack lowered, Green-White-Green rose, and the city by the lagoon became the symbol of a new nation determined to prove it could govern itself.

The First Republic was constructed as a delicate balancing act. Three major regions—North, East, and West—held power like rival kingdoms forced into a fragile marriage. Lagos, though a small federal territory, was the neutral capital, the meeting point where politicians converged to bargain, scheme, and argue.

For a moment, it worked. The early 1960s were filled with optimism: schools expanded, universities sprouted, industries grew. But the dream was fragile. Beneath the veneer of progress lay deep ethnic suspicion and fierce regional competition. Each premier ruled his region like a fortress, while Lagos became the battlefield where these rivalries clashed under the pretense of federal politics.

Fault Lines in the Republic

The seeds of collapse were planted early.

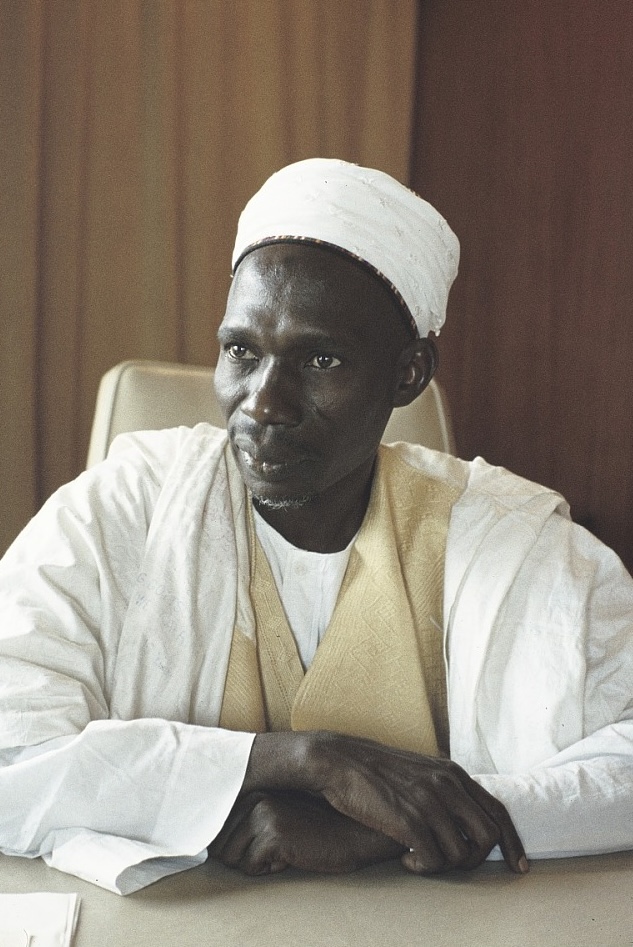

The Northern People’s Congress (NPC), led by Sir Ahmadu Bello in the North, held the largest numbers.

The National Council of Nigerian Citizens (NCNC), under Nnamdi Azikiwe, dominated the East. In the West, the Action Group (AG), led by Chief Obafemi Awolowo, was the most disciplined opposition.

But the Republic was never about ideology; it was about arithmetic and alliances. Lagos became the chessboard where coalitions were made and broken. Awolowo’s imprisonment in 1963 for alleged treason weakened the AG and deepened Yoruba resentment.

Meanwhile, the NPC-NCNC alliance created a federal government that seemed more about power-sharing than nation-building.

Corruption scandals spilled into newspapers. Census figures were inflated and disputed, each region accusing the other of manipulation. Lagos, the capital, became a cauldron of petitions, protests, and propaganda. The dream of independence had turned into a contest of betrayal.

The 1964 Federal Elections – Ballots and Betrayals

The 1964 federal elections were meant to renew the Republic’s mandate. Instead, they poisoned it.

In Lagos, campaign posters plastered the walls of Tinubu Square and Yaba bus stops, promising hope but dripping with fear. Parties accused each other of intimidation. Ballot boxes were seized. Voter registers were manipulated. Across the country, boycotts and violence erupted.

When the results were declared, the ruling NPC and its allies claimed victory. The opposition United Progressive Grand Alliance (UPGA), a coalition of Azikiwe’s NCNC and Awolowo’s AG, cried foul. Lagos buzzed with rumors that the elections would not be accepted. Street protests flared.

The crisis paralyzed the Republic. For weeks, Nigeria had two governments in theory but none in practice. President Azikiwe, symbolic head of state, hesitated to endorse results he considered tainted. Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa, under pressure from the NPC, moved ahead as if legitimacy were unquestionable.

Lagos became the stage of a dangerous standoff. Every decision made in Parliament echoed like a gunshot in the streets.

The Wild, Wild West and Lagos in Flames

While the federal elections strained the Republic, the regional elections of 1965 tore it apart.

In the Western Region, rival factions of the Action Group fought bitterly, with Chief Samuel Akintola aligned to the NPC and Awolowo loyalists resisting. The election was a charade of ballot stuffing, intimidation, and open thuggery.

The people of the West revolted. Protesters filled Ibadan, Ijebu, and Abeokuta, torching houses of politicians and hunting down known thugs. The violence earned the region its grim nickname: the “Wild, Wild West.”

But Lagos was not immune. Refugees poured into the capital. Rumors of killings upcountry electrified the city’s motor parks. Western students in Lagos universities marched, chanting against corruption. Newspapers carried headlines that read like obituaries for democracy.

For the first time since independence, Lagos felt less like a capital of hope and more like a city waiting for the hammer to fall.

The Coup Whispers in Lagos

By late 1965, the Nigerian Army was restless.

Young officers, many trained abroad, looked at the chaos in politics with contempt. In the barracks of Lagos, whispers grew louder: politicians were destroying the nation; soldiers would have to save it.

The public fed those whispers. In beer parlors of Mushin and Surulere, men argued that only the army could stop the madness. Newspapers carried thinly veiled warnings. Even some civil servants quietly hoped for intervention.

In Lagos, the ground was shifting. Trucks of soldiers patrolled the streets with heavier presence. The Parliament House felt like a fortress. Ministers moved with anxiety. It was as if everyone knew the Republic was dying, but no one wanted to be the first to pronounce it dead.

January 15, 1966 – The Night of Long Knives

The coup arrived like lightning.

In the early hours of January 15, 1966, Lagos woke to the crack of gunfire. Rebel soldiers, led by young majors like Chukwuma Kaduna Nzeogwu and Emmanuel Ifeajuna, struck at the heart of government. Politicians and senior officers were targeted for elimination.

Prime Minister Tafawa Balewa was abducted and later found dead. Finance Minister Festus Okotie-Eboh was executed. Top military officers were killed.

For ordinary Lagosians, the city was plunged into fear. Rumors flew faster than bullets. Some thought civil war had begun. Others whispered of ethnic vengeance. By morning, Lagos was under military control. The Republic had fallen in a single night of betrayal.

Lagos Under Ironsi – A Fragile Peace

In the coup’s aftermath, Major General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi emerged as Head of State. From Lagos, he promised stability. Soldiers now filled the streets, Parliament was silenced, and politicians faded into obscurity.

But peace was fragile. Many in the North saw the coup as an Igbo plot, since most of the slain leaders were Northerners while Ironsi, an Igbo, now led the country. In Lagos, political whispers turned into ethnic suspicion. Markets hummed with fearful gossip. Mosques and churches prayed for calm.

Ironsi’s attempt to centralize power through Decree No. 34 further deepened mistrust. What had begun as relief in Lagos slowly turned into tension.

Betrayals and Counter-Coup

By July 1966, the fragile peace shattered again.

Northern officers, enraged by the killings of their leaders and suspicious of Ironsi, staged a counter-coup. Ironsi himself was murdered in Ibadan, and young officers seized control. Lagos once more became the capital of uncertainty, where governments rose and fell at gunpoint.

The First Republic was long dead. What remained was a cycle of coups, betrayals, and eventually the Civil War. Lagos, the city that had once symbolized independence, had become the stage where Nigeria’s first democratic experiment bled to death.

The Lessons of Collapse

The fall of the First Republic was not a sudden accident; it was a slow unravelling. Lagos merely concentrated the nation’s contradictions—ethnic rivalry, corruption, electoral violence, and betrayal of public trust.

The riots of the West, the rigged elections, the arrogance of politicians, and the impatience of soldiers all converged in Lagos, turning the city into the graveyard of Nigeria’s first democratic hope.

Even today, the story feels painfully familiar. Nigeria’s politics still wrestles with the ghosts of that era—regional suspicion, flawed elections, and the lurking shadow of military intervention.

Conclusion: When Lagos Became the Graveyard of Democracy

History records January 1966 as the official end of the First Republic. But in truth, the Republic had been dying long before that night. Lagos had watched it rot from within: in the betrayals of elections, in the riots of the West, in the whispers of soldiers.

The coup was only the final act.

And so Lagos, once the city of independence celebrations, became the city where Nigeria’s first democratic experiment collapsed in blood, fire, and betrayal.

The lesson remains: when politics turns into war, democracy dies long before the first soldier fires a gun.

Discussion about this post