Nigeria’s history of conflict is often told through the lens of generals, militants, and politicians, yet many of the most consequential negotiations were shaped by women.

Mothers, market leaders, teachers, and community organizers stepped into spaces where authority was rarely extended to them, used moral authority, cultural legitimacy, and lived experience to influence outcomes and protect communities.

This article delves into the stories of these women—the negotiators who engaged insurgents, confronted military commanders, challenged multinational corporations, and advocated for communities whose voices were otherwise silenced. Their courage, persistence, and strategic influence reveal how women have quietly, but decisively, shaped Nigeria’s most dangerous negotiating tables and the fragile peace that followed.

Mothers of the Biafran War

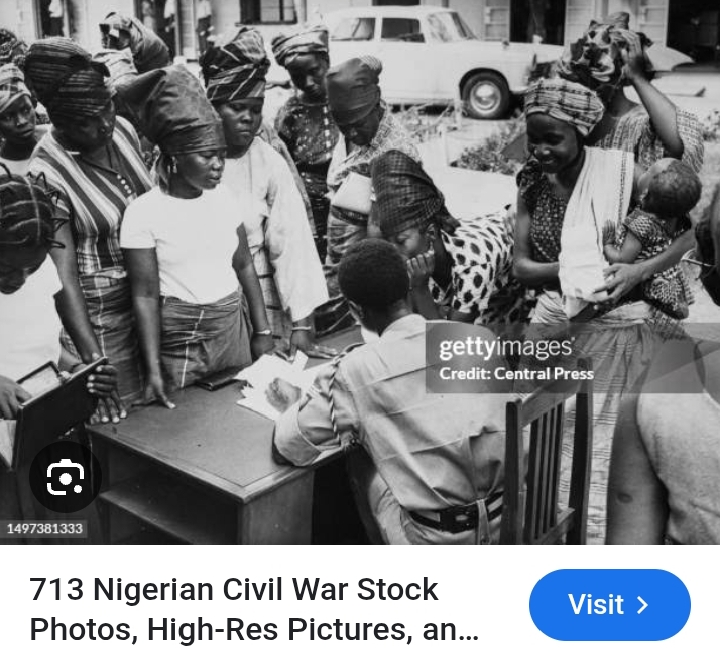

The Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970) remains one of the country’s darkest tragedies, a conflict that starved more than a million people to death. Yet in the shadows of starvation and bombs, women organized. While politicians debated on the global stage, women in Eastern Nigeria risked their lives to negotiate survival for their children.

Igbo market women—long known as the economic engines of their towns—stepped into roles that history has under-documented. In some villages, it was women who approached federal soldiers with bowls of food and calabashes of palm wine, pleading for passage of relief supplies. They spoke not as politicians, but as mothers. And in many cases, soldiers, confronted with the face of their own mothers in these women, relented.

Beyond the frontlines, international negotiations were quietly supported by Nigerian women in exile.

Flora Nwapa, Nigeria’s first female novelist, turned her international stature into an advocacy platform for starving Biafran children, pressing Western aid organizations to act. Her literature became a negotiating tool in itself—humanizing a war that the world saw only in numbers.

The lesson of this era was simple: when the men spoke of territory, women spoke of stomachs. And stomachs were the difference between life and death.

The Market Women Who Faced Generals

Military regimes in Nigeria were notorious for their intolerance of dissent. Decree after decree silenced unions, journalists, and opposition politicians. Yet one group of citizens refused to be muted: the market women.

These women controlled the food distribution networks in Lagos, Ibadan, Onitsha, and Kano. They could crash economies by withdrawing goods from the market—and the military rulers knew it. This gave them an unusual bargaining chip.

During the austerity years of the 1980s, when General Ibrahim Babangida’s Structural Adjustment Program sent inflation soaring, it was Lagos market women who staged protests that forced the regime to the table.

Alhaja Abibatu Mogaji, the formidable Iyaloja of Lagos (and mother of future politician Bola Tinubu), famously stared down uniformed officers, insisted that the survival of her traders required policy concessions.

These weren’t negotiations in wood-paneled conference rooms—they were tense confrontations in marketplaces surrounded by soldiers. Women demanded access to affordable rice, kerosene, and safe market stalls. They were bargaining not with documents, but with the threat of nationwide paralysis.

Theirs was a dangerous game. Soldiers once stormed Oyingbo market, brutalizing women to break their resistance. Yet even bruised and bloodied, the women regrouped. They had discovered a truth that dictators loathed: controlling food meant controlling the streets, and controlling the streets meant controlling legitimacy.

Niger Delta’s Unarmed Warriors

Fast-forward to the 1990s and 2000s: Nigeria’s oil-rich Niger Delta became a battlefield. Militants kidnapped oil workers, pipelines exploded under sabotage, and multinational companies withdrew in fear. The Nigerian state responded with military deployments that often left villages in ashes.

Yet, in the middle of this violence, Niger Delta women marched. Sometimes clad only in wrappers, sometimes stripping naked in symbolic defiance, they walked into oil company compounds and military checkpoints. To humiliate men in traditional Niger Delta culture, a woman baring her naked body was a curse, a shame too deep to ignore.

Women like Ledum Mitee’s sister-groups in Ogoni and the Ijaw Women of Peace Movement became unarmed negotiators. They demanded environmental justice, compensation for oil spills, and protection from military raids.

In 2002, hundreds of Itsekiri and Ijaw women occupied ChevronTexaco’s Escravos oil terminal for over ten days, refusing to leave until their demands for schools, clinics, and jobs were met. Facing the world’s largest oil company and backed only by their bodies, they won concessions no armed militia had achieved.

These women turned cultural symbolism into negotiating power. While the men fought with bullets, the women fought with shame, solidarity, and the unspoken fear that killing unarmed mothers would forever taint the state.

Mothers of Chibok

In 2014, the kidnapping of 276 schoolgirls from Chibok by Boko Haram shook the world. The Nigerian government dithered, first denying the scale of the abduction, then fumbling rescue attempts. But the mothers of Chibok refused to stay silent.

Clad in simple wrappers and scarves, they sat in Abuja’s Unity Fountain, day after day, their placards demanding one thing: “Bring Back Our Girls.” What began as a local outcry became a global campaign, amplified by activists like Oby Ezekwesili. But at its heart, it remained a mothers’ negotiation—one in which grief-stricken women forced the Nigerian state to acknowledge its failure.

Some of these mothers later engaged in direct negotiations with Boko Haram intermediaries, traveling across dangerous terrain to beg for their daughters’ lives. Their courage opened channels that led to the eventual release of more than 100 girls.

At a time when Boko Haram seemed untouchable, it was unarmed women—grieving, ordinary women—who breached the terror group’s fortress of fear.

The Unseen Cost of Negotiation

Sitting at Nigeria’s most dangerous negotiating tables often came at a brutal cost for women. They were threatened, harassed, even assaulted. Many were erased from the official record, their contributions buried under the names of male politicians and generals.

Some, like Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti, who had long been a negotiator between women’s groups and colonial authorities, paid the ultimate price. In 1978, soldiers stormed her Abeokuta home during a protest, flinging the aging activist from a window. She never recovered.

Negotiating in Nigeria has never been gender-neutral. For women, the risks doubled: they fought not only authoritarian governments or armed militias, but also the cultural prejudice that dismissed them as outsiders at the table. Yet, precisely because they were outsiders, they often brought unexpected leverage—the moral authority of motherhood, the control of food, the symbolism of the female body, the persistence of grief.

The Forgotten Architects of Peace

History remembers generals, politicians, and militants. But history often forgets the women who walked into the lion’s den with nothing but their voices, wrappers, and courage.

From the starving children of Biafra to the oil-stained creeks of the Niger Delta, from the burning markets of Lagos to the broken classrooms of Chibok, Nigerian women have been negotiators of last resort. They were the ones who turned tears into bargaining chips, hunger into a weapon, and motherhood into diplomacy.

In telling their stories, we rewrite the narrative of power in Nigeria. Negotiation has never been only about guns, oil, or decrees. It has also been about the quiet strength of women who refused to be silenced.

The women who sat at Nigeria’s most dangerous negotiating tables may not have left behind statues or monuments. But their legacy endures in every child fed, every village spared, every girl returned, and every fragile peace wrestled out of chaos.

And perhaps, when Nigeria next stands at the edge of war, it will remember: sometimes, the fiercest negotiators do not carry titles, guns, or briefcases. Sometimes, they simply carry the unyielding weight of motherhood.

Discussion about this post