Long before Nigeria became a mosaic of bustling cities, political intrigue, and modern infrastructure, there existed places where the earth itself seemed to carry memory. Across the northern savannahs and the edges of ancient trade routes, structures of mud and timber rose, weathered by centuries, yet unyielding to time. Their walls have witnessed empires rising and falling, colonial ambitions, and the quiet persistence of faith. These are Nigeria’s oldest mosques—silent repositories of history, culture, and mystery.

Some are barely visible against the ochre landscape, their forms blending with the surrounding terrain, while others rise in stark contrast, commanding attention with intricate wooden beams and carved facades. For centuries, they have been more than places of worship—they are chronicles etched in mud, plaster, and sweat; living testimonies to the ingenuity and resilience of the communities that built them.

Each mosque holds a story: tales of scholars who shaped Islam in West Africa, rulers who sought legitimacy through faith, and ordinary people whose devotion turned fragile mud into enduring sanctuaries.

This article journeys into the heart of Nigeria’s oldest mosques—examining their history, architecture, cultural significance, and the mysteries that make them living relics.

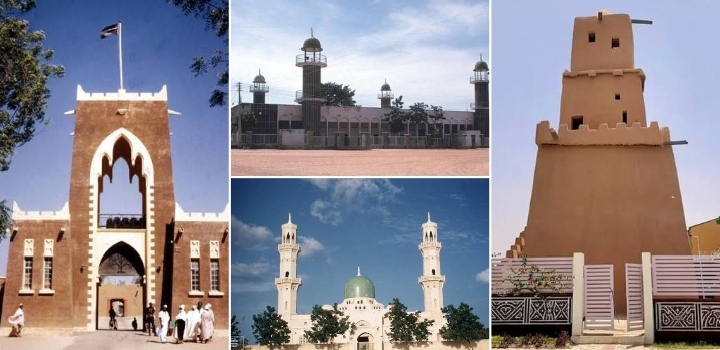

Nigeria’s Oldest Surviving Mosques

1. The Great Mosque of Kano (Jama’at Kano)

Birth of a Monument: Rumfa’s Vision for a Spiritual Capital

The story of the Great Mosque begins in the 15th century, when Muhammad Rumfa, one of Kano’s most influential rulers, envisioned a mosque that would anchor his capital as both a political and spiritual stronghold. Rumfa was not just a king; he was a reformer who deepened Islam’s roots in Kano, building institutions that blended governance with faith.

The mosque he commissioned was unlike anything the Hausa people had seen — massive earthen walls, bold symmetry, and a prayer space capable of gathering thousands. It wasn’t merely a house of prayer; it was a statement: that Kano had entered a new era where Islam was inseparable from the city’s identity.

Mud Walls and Sacred Towers: Sudano-Sahelian Architecture in Kano

The Great Mosque followed the Sudano-Sahelian style, a tradition stretching across West Africa from Mali’s Djenné to Niger’s Agadez. Its most striking feature was the use of mud and timber, which kept the interiors cool despite Kano’s blistering heat.

From afar, its minaret rose like a sentinel of clay, guiding traders and travelers along the trans-Saharan routes. Each layer of mud was not just functional but symbolic — earth shaping eternity, fragile yet enduring.

Survival Through Time: Fire, Reconstruction, and the Endurance of Faith

The Great Mosque has not survived without scars. Over the centuries, it endured fires, collapses, and reconstructions. Each rebuild brought changes, but the soul of Rumfa’s vision remained. Colonial administrators in the early 20th century even attempted to modernize it, but the community resisted, preferring restoration to replacement.

What stands today may not be the exact bricks Rumfa laid, but the lineage of its worship is unbroken. It is a mosque of continuity — where the Friday prayers of 2025 echo the same call first heard in the 1400s.

From Sultan to Emir: Political Power and Sacred Authority Intertwined

The Great Mosque also carried political weight. For centuries, it was the stage where sultans, later emirs, asserted authority. A khutbah (Friday sermon) delivered in the mosque carried political endorsement, binding ruler and ruled under the same sacred roof.

Even today, the Emir of Kano’s presence in the mosque is more than ceremonial — it is a thread tying the present city to its Rumfa-era beginnings.

The Great Mosque in the Memory of Kano People

Ask an elder in Kano about the mosque, and you won’t just hear about prayer. You’ll hear about market days that started with its call, coronations sanctified in its walls, and generations who measured their lives by its rhythm. To them, it is not just the oldest mosque; it is the heart of Kano itself.

2. Gidan Rumfa (Emir’s Palace Mosque)

The Palace Where Faith Meets Power

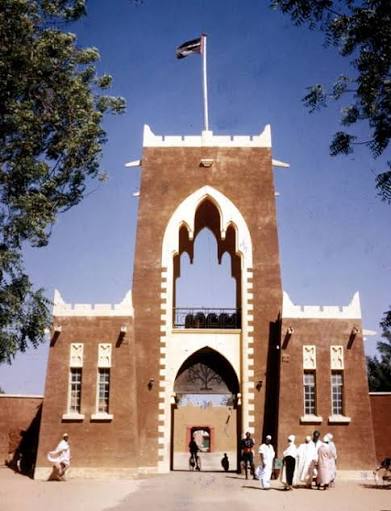

Built in the late 15th century, Gidan Rumfa — the Emir’s Palace — remains one of the oldest continuously inhabited palaces in West Africa. Within its sprawling walls lies a mosque that served as both a royal chapel and political pulpit.

Unlike the Great Mosque, which gathered the city, the palace mosque gathered the court — nobles, scholars, guards, and servants. It was a reminder that governance in Kano was always kneeling before God.

Behind the Walls: Islam as the Language of Governance

For centuries, decrees in Kano were often made after prayers within Gidan Rumfa’s mosque. Scholars known as ulama advised rulers, blending Islamic jurisprudence with Hausa customs. Here, Islam was not just private devotion but public administration.

The Emir’s Court and the Friday Prayers: A Tradition That Never Broke

Every Friday, the Emir of Kano leads his court to prayer in the palace mosque before moving to the larger Great Mosque. This ritual — small mosque to great mosque — symbolizes the Emir’s dual identity: a private servant of God and a public guardian of faith.

Mud, Courtyards, and Intrigue: Architecture of Authority

The mosque’s architecture reflects palace life: enclosed courtyards, low mud walls, and shaded corridors. Unlike monumental mosques, it is intimate, hidden, and political. The secrecy of its space allowed rulers to blend worship with strategy.

The Emir’s Palace Mosque in Today’s Kano

Today, Gidan Rumfa is a tourist attraction, but its mosque still functions. For locals, it is a reminder that the palace is not merely political real estate but sacred ground. It is where power bows before prayer, just as it did 500 years ago.

3. Gobarau Minaret (Gobarau Mosque, Katsina)

The Tower That Watched Centuries Pass

Few structures in Nigeria stir as much awe as the Gobarau Minaret in Katsina. Rising almost 50 feet, it looks more like a fortress tower than a mosque minaret. Built in the 15th century, it is one of the oldest standing Islamic structures in West Africa.

Muhammadu Korau’s Legacy: The First Muslim King of Katsina

The mosque was constructed under Sarkin Katsina Muhammadu Korau, the first Muslim ruler of the kingdom. His reign marked a turning point when Islam moved from outsider faith to royal endorsement. Gobarau became both a mosque and a statement: Katsina was now firmly an Islamic city-state.

Learning Beneath the Minaret: Gobarau as University Before Universities

For centuries, Gobarau was not just a mosque — it was a center of scholarship. Students studied Qur’an, mathematics, astronomy, and medicine under its mud walls. In many ways, it was a university before Ahmadu Bello University or Bayero University ever existed.

The Mystery of the Tilt: Legends Around the Old Minaret

Today, the minaret leans slightly, its mud frame weathered by centuries. Locals whisper legends — that it leans in reverence toward Mecca, or that it will collapse on Judgment Day. Whether myth or physics, the tilt has only deepened Gobarau’s aura of mystery.

Gobarau in Modern Katsina: From Symbol to Relic

Though no longer the central mosque, Gobarau remains a sacred relic. Tourists marvel, locals protect it, and scholars lament that without preservation, Nigeria could lose one of its rarest medieval treasures.

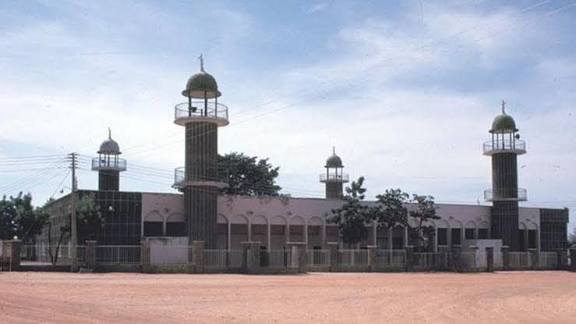

4. The Friday Mosque of Zaria (Masallaci Juma’a)

Durugu the Master Builder: Hausa Architecture in Motion

Unlike the older Kano and Katsina mosques, Zaria’s Friday Mosque emerged in the 19th century, during the Fulani jihad era. It was the work of Muhammadu Durugu, a master Hausa builder renowned for his skill with mud architecture.

The Jihad That Built Mosques: Faith, Conquest, and Expansion

The mosque’s construction was tied to the jihad movement led by Usman dan Fodio. As Fulani rulers consolidated Zaria, building a Friday mosque was both a spiritual necessity and a political declaration.

A Mosque at the Heart of Zazzau’s Identity

The mosque became central to Zaria’s identity. Here, sermons were not only about religion but about shaping a new political order under Fulani leadership.

How the Friday Mosque Shapes Zaria’s Urban Landscape

Built in the heart of Zaria, the mosque shaped the city’s growth. Markets, schools, and homes radiated from its presence, making it both a spiritual and economic anchor.

The Mosque That Binds Generations

Generations of Zaria families recall milestones — births, marriages, funerals — tied to the Friday Mosque. Its mud walls are not just structures but family diaries written in prayer.

Oral Histories and Spiritual Narratives

Beyond their physicality, Nigeria’s oldest mosques carry intangible stories—narratives that blend faith, mystery, and human experience. In Katsina, elders recount that the Friday Mosque’s foundations are aligned with the stars, a practice that integrates spiritual belief with astronomical knowledge. Some believe that the mosque’s walls emit a faint resonance during early morning prayers, an echo of past generations reciting Quranic verses.

Similarly, in Borno, local storytellers describe hidden chambers beneath the Jibril Mosque, purportedly used to store manuscripts containing forgotten histories, legal rulings, and scientific treatises. While archaeologists have yet to uncover these chambers, the persistence of such oral narratives speaks to the mosque’s role as a vessel of memory, where fact and legend intertwine.

These stories also reveal the human dimension of Islamic architecture in Nigeria. They reflect how communities interpreted divine will, societal order, and cultural identity through bricks, mud, and timber. Every mosque becomes a palimpsest of human aspiration, a silent testament to generations who labored, prayed, and dreamed within its walls.

Colonial Encounters and Preservation Challenges

The arrival of European colonial powers in the 19th and early 20th centuries introduced new pressures on Nigeria’s mud mosques. British administrators often dismissed them as “primitive structures,” favoring stone or brick for new administrative centers. Yet, these judgments failed to account for the profound resilience and symbolism embedded in mud architecture.

During colonial campaigns, some mosques were damaged or repurposed. In Kano, British records note attempts to convert parts of the Gidan Rumfa complex for military use, threatening centuries of heritage. Local communities resisted, repairing and restoring the mosques with remarkable dedication.

Modern preservation presents new challenges. Climate change, urban expansion, and neglect have accelerated the deterioration of mud structures. Conservationists argue for careful documentation, controlled restorations, and community-led initiatives. Yet every restoration is a delicate balance: over-modernization can strip the mosque of its historical authenticity, while neglect risks erasing centuries of memory.

Modern Significance – Faith, Tourism, and Cultural Identity

Today, Nigeria’s oldest mosques serve multiple roles. They are active houses of worship, attracting devout Muslims for daily prayers and annual festivals. They are heritage sites, drawing historians, architects, and tourists eager to witness living examples of Sudano-Sahelian architecture. They are symbols of cultural resilience, reminders of Nigeria’s capacity to preserve history amid the pressures of modernization.

The annual Sallah celebrations in Kano and Zaria see thousands congregate in these ancient spaces, where mud walls reverberate with collective devotion. Tour guides recount stories of ancestors, dynasties, and scholars, blending historical fact with community pride. Photographers capture the interplay of light and shadow across the textured surfaces, documenting the artistry that has survived centuries.

For local communities, these mosques are anchors of identity, binding them to a shared past while inspiring younger generations to value their heritage. They remind Nigerians that history is not only written in books but in earth, sweat, and devotion.

Enduring Legacy and Mysteries

Nigeria’s oldest mosques stand as silent witnesses to history. They are chronicles written in mud, carved by generations who dared to blend faith, artistry, and ingenuity. Their walls have weathered empires, colonial rule, and climate, yet they continue to inspire wonder and devotion.

The mysteries embedded in these structures—hidden chambers, forgotten manuscripts, stories whispered across centuries—invite further exploration. They challenge historians, archaeologists, and visitors alike to look beyond appearances, to question what is preserved and what remains hidden.

As we reflect on these sacred spaces, we are reminded that history is not static. It lives in the mud, in the prayers, in the hands that replaster walls each generation, and in the mysteries that endure, waiting for those willing to listen. Nigeria’s mud mosques are more than buildings—they are living monuments, eternal in their testimony to human faith, creativity, and resilience.

Discussion about this post