The gates, in late September 2017 of Iwo palace had never felt so heavy. A subtle tension hung over the sprawling compound, where centuries of lineage, legend, and ritual had converged into a singular identity. This was not merely a moment of administrative decree; it was a seismic shift in the spiritual heartbeat of the town. Long before modernity carved streets and corridors into Nigeria’s urban landscape, the palace had been a living organism, its walls breathing stories of ancestors, warriors, and kings who once held the weight of empires in their palms.

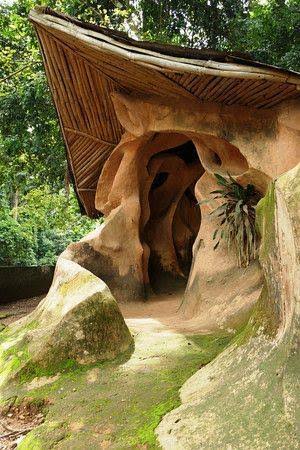

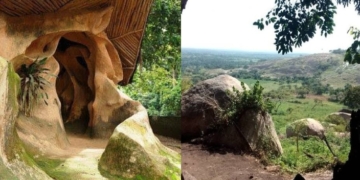

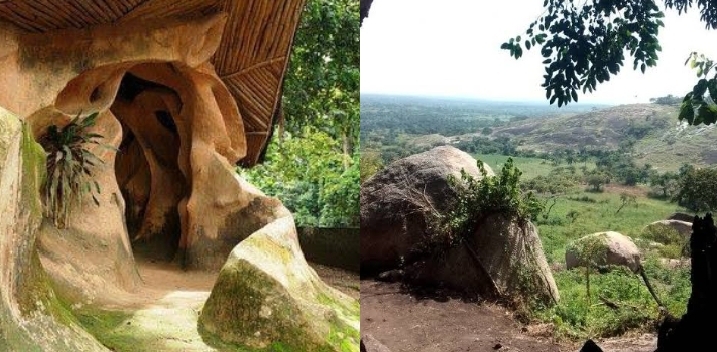

The shrine at the heart of this quiet storm had existed for eight centuries. It was more than stone, wood, and iron; it was the repository of collective memory, a tangible pulse of Iwo’s cultural DNA.

To relocate it was to challenge the invisible tether that had bound generations to an ancestral rhythm. Residents and palace aides alike debated in hushed tones whether such an act was daring, necessary, or sacrilegious.

For those who understood the layers of history entwined with the shrine, it was as though the palace itself was mourning, acknowledging that centuries of spiritual guardianship were being lifted and carried elsewhere.

The tension was not easily resolved. Every ritual performed in preparation for the relocation became a subtle negotiation between the past and the future, a quiet dialogue between the king and forces far older than any royal decree.

The Shrine as Historical Conduit: Eight Centuries of Memory (c. 1200–2017)

The shrine traced its origin to the early 13th century, around c. 1200, a period when the Yoruba kingdoms of Iwo were consolidating power and ritual practice became inseparable from governance. Each artifact—wooden carvings, iron implements, sacred inscriptions—served as a record of dynastic succession, wars, alliances, and moral codes.

The announcement of its relocation by Oba Abdulrasheed Adewale Akanbi, the Oluwo of Iwo, marked a decisive moment in the palace’s long narrative, one that intertwined tradition, modern governance, and the unpredictable consequences of change.

Moving the shrine was more than a physical act; it was a recalibration of the town’s spiritual compass, a moment that required careful negotiation between ancestral authority and modern oversight.

During the relocation, it became apparent how deeply embedded the shrine was in Iwo’s communal identity. Local residents recalled stories passed down through generations: the shrine’s counsel had guided decisions during droughts, conflicts, and epidemics, its presence a stabilizing force even amid colonial incursions. Scholars noted that displacing such a repository of memory risked disrupting the moral and spiritual rhythms that had guided the community for centuries.

Throughout September 2017 palace aides meticulously prepared the artifacts. Elders performed purification rituals, offerings were laid to honor past rulers, and symbolic gestures were made to reassure ancestral spirits. Even the timing of movements—the hour, the day, the sequence of objects—was carefully calculated. These measures reflected an understanding that while governance had modernized, spiritual authority demanded respect and attentiveness.

Few days into September’s month end , the shrine’s relocation was complete. Yet the palace felt different. Some aides reported an uncharacteristic stillness in halls where life and ritual had always thrived. Animals on palace grounds behaved unusually; shadows seemed longer, and certain corridors felt charged with quiet energy. Observers interpreted these subtle signs as a reminder: the shrine’s influence extended beyond its physical location, and centuries of spiritual oversight required acknowledgment, even in a modernized framework.

Public Perception: Between Reverence and Controversy

News of the shrine’s relocation reached broader Iwo society by late 2017 Townspeople reacted with a mix of admiration, concern, and cautious curiosity. Supporters praised the Oluwo of Iwo for taking a bold step: preserving heritage while aligning sacred spaces with contemporary governance. They argued that centralizing spiritual oversight reduced risks associated with ritual mismanagement and strengthened the moral authority of the palace in guiding civic affairs.

Conservatives voiced apprehension. Long-standing taboos dictated that sacred objects should remain undisturbed, and anecdotal accounts of foreboding dreams, subtle illness among those who handled relics, and unusual natural occurrences circulated widely. These reactions highlighted a persistent tension in Nigerian traditional societies: the intersection of spiritual belief, communal memory, and modern administrative logic.

Media coverage documented these debates, often framing the story as a conflict between tradition and modernity. Journalists highlighted the careful, unobtrusive manner in which the palace conducted the relocation, noting that minimal fanfare allowed communities to interpret the event on their own terms. This approach mitigated some public concern while preserving a sense of sacred gravitas around the shrine.

Days later, the shrine had settled into its new location. It began attracting visitors, scholars, and spiritual observers, each interpreting its presence in light of both historical continuity and contemporary adaptation. The shrine’s relocation became a symbol not only of cultural preservation but also of leadership: the delicate balance between honoring centuries of tradition and embracing the necessities of modern governance.

Ritual Negotiation: Modern Governance Meets Ancient Spirituality

The logistical execution of the shrine’s relocation was deeply intertwined with ritual negotiation. Palace aides, spiritual custodians, and elders collaborated, ensuring that sacred protocols were preserved even as administrative procedures guided the process. Daily activities combined formal ceremonial practice with precise logistical planning, demonstrating a rare convergence of ancient and contemporary knowledge systems.

Oba Abdulrasheed Adewale Akanbi personally oversaw the relocation. He engaged in every ritual act, from prayer to artifact handling, signaling that leadership was not merely administrative but spiritual. Elders and aides observed subtle cues—timing of movements, sequence of objects, orientation of sacred implements—interpreted as essential to maintaining ancestral favor. These practices underscored the palace’s awareness that disruption could have unforeseen consequences, both metaphysical and social.

Unusual occurrences were reported during this period. Electrical disturbances, strange sounds in empty corridors, and odd movements of ceremonial objects contributed to a narrative of heightened sensitivity around the shrine. While some dismissed these as coincidences, palace observers considered them signals from ancestral forces, emphasizing the living presence of tradition even amidst structural change.

By the conclusion of the relocation, a sense of equilibrium had emerged. Ritual obligations had been honored, historical continuity had been respected, and administrative objectives had been achieved. The process became a template for how Nigerian monarchs could navigate the complex interface between sacred tradition and modern leadership demands.

The Shrine’s Enduring Resonance: Spiritual Life After Relocation

The shrine settled into its new designated location within the palace precinct, and yet, its presence continued to ripple through Iwo. Visitors to the palace noted a change in atmosphere: quiet but persistent energy that seemed to hover around the relocated relics. For many, the shrine was no longer just a physical entity; it had become a living conduit between the past and the present, a touchstone reminding residents and leaders alike that history is not inert but constantly interacting with human choices.

Local spiritual leaders remarked that the shrine retained its potency despite relocation. Ritual consultations, previously held at the original site, were gradually moved to the new location, maintaining the ancestral protocol while adapting to spatial changes. This careful preservation of ceremonial structure highlighted the foresight of Oba Abdulrasheed Adewale Akanbi in ensuring that modernization did not sever the living thread of tradition. The shrine’s voice, whether metaphorical or literal in practice, continued to guide communal decision-making, moral judgment, and festival observances.

At the same time, some residents reported subtle, unusual phenomena linked to the relocation. Stories circulated about objects found slightly displaced after ritual activities, shadows appearing in unlit halls, or drums echoing faintly without human touch. Scholars and anthropologists visiting Iwo framed these occurrences as the community’s collective consciousness interacting with spiritual memory, suggesting that sacred spaces hold resonance beyond their immediate materiality. The shrine had, in effect, expanded its presence, teaching the town that tradition could adapt spatially without losing its authority.

The relocation also became a point of reflection for younger generations, who often engage with heritage differently than elders. School programs, community discussions, and cultural seminars referenced the event as a case study in reconciling spiritual history with modern civic responsibility. These conversations underscored the lesson that cultural continuity requires both reverence and adaptability. The shrine’s enduring resonance, therefore, was not merely a matter of ritual efficacy but a living demonstration of leadership, negotiation, and historical consciousness.

Long-Term Impact on Palace Governance and Community Leadership

The relocation did not merely affect spiritual practice; it reshaped governance within the palace itself. By overseeing the shrine’s careful movement, Oba Abdulrasheed Adewale Akanbi reinforced a model of leadership that blended ceremonial authority with administrative diligence. Palace aides were trained to manage both spiritual and logistical responsibilities, creating a framework in which sacred and civic governance could coexist without conflict.

Community leaders observed changes in how the palace engaged with residents. Regular consultations, previously confined to ritual matters, increasingly incorporated ethical oversight, civic advice, and conflict mediation. The shrine’s relocation became a symbol of the Oluwo’s vision: a palace that honors tradition while responding to contemporary societal needs. In essence, it demonstrated that cultural authority could adapt, becoming a stabilizing force rather than a source of rigidity.

Subtle indicators suggested that the shrine’s relocation had longer-term implications for communal cohesion. Neighborhoods and town committees reported increased participation in cultural events, greater awareness of heritage practices, and heightened respect for ancestral consultation. Scholars interpreted this as evidence that tangible acts—such as moving a centuries-old shrine—could catalyze social transformation when guided by intention, transparency, and moral integrity.

Palace records and oral histories began incorporating the relocation as a defining moment in Iwo’s modern governance. The event became a reference point for discussions about the ethical stewardship of cultural assets, the balance between spiritual authority and administrative oversight, and the lessons derived from confronting centuries-old structures of power.

Comparative Reflections: Lessons from Other Monarchic Practices (Oyo, Benin, Ekiti)

The Iwo shrine relocation resonates with broader patterns observed among Yoruba and Edo monarchies. Similar instances—whether in Oyo, where palace relics were periodically safeguarded during political upheavals, or Benin, where sacred bronzes faced historical displacement—demonstrate that the tension between preservation and adaptation is not unique. In each case, the successful negotiation of tradition with evolving civic realities has required careful stewardship, ritual observance, and moral reflection.

In Ekiti, for instance, documented relocations of monarchic relics during crises in the early 20th and 21st centuries mirrored some aspects of Iwo’s approach: community involvement, elder consultation, and ceremonial negotiation. Analysts suggest that these events collectively illustrate a principle intrinsic to Nigerian traditional governance: sacred authority survives when it is respected but also actively interpreted and integrated with contemporary social demands.

By drawing these comparisons, the Iwo case provides a contemporary lens on ancestral wisdom. Leadership is revealed as an ongoing dialogue with history, a dynamic process of listening to the past, reading the present, and shaping the future. The relocation becomes a metaphor for all societies negotiating heritage and progress, demonstrating that ethical cultural adaptation is not merely permissible but essential for sustainable governance.

Final Thoughts: The Echoes of What Was Moved

The shrine may no longer occupy its original place within Iwo palace, yet its presence lingers in every shadowed corridor, every whispered ritual, and the collective memory of those who witnessed its passage. What was moved carried more than wood, iron, and centuries of carvings—it carried the weight of history, the tension of tradition, and the quiet authority of ancestors.

The palace has adapted, the town has reflected, and life continues, but a subtle awareness remains: actions taken in the corridors of history are never without echo. The strange aftermath of the relocation is not measured in spectacle but in the enduring dialogue it provokes between past and present, visible and unseen, leadership and legacy.

Oba Abdulrasheed Adewale Akanbi’s decision reminds us that tradition is not a static monument; it is a living conversation, capable of being guided, challenged, and honored simultaneously. And as the shadows of the shrine settle into their new place, one truth remains unmistakable—some movements, however deliberate, leave traces that time cannot erase.

Discussion about this post