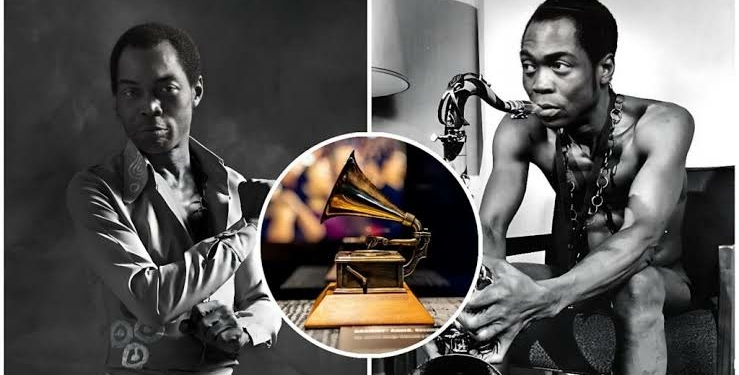

The silence was never loud, but it was heavy. For decades the world danced to rhythms born in a cramped Lagos rehearsal space while the institutions that crown musical greatness looked elsewhere. Fela Anikulapo Kuti did not need trophies to be immortal, yet the absence of formal recognition from the most powerful music academy lingered like an unanswered question. How could a man whose sound reshaped continents remain officially unacknowledged for so long.

Fela died in 1997, but his music refused burial. Each generation rediscovered him through protest movements, sampling culture, political art, and the growing global hunger for African narratives told on African terms. His songs did not age, they matured. They adapted to new struggles, new cities, new accents, and new audiences who felt spoken to rather than entertained.

The Recording Academy did not ignore Fela, but it struggled to place him. He existed outside categories, outside comfort, outside the polite boundaries of industry recognition. His work demanded context, confrontation, and courage, qualities institutions often approach slowly. Recognition was not denied outright, it was deferred again and again.

Now nearly three decades after his death, the Grammys have chosen to look backward in order to correct the present. The question is not why Fela deserves this honour. The deeper question is why it took the world’s most powerful music institution this long to say it out loud.

The Era When Fela Was Too Political for Global Comfort

Fela emerged at a time when global music institutions preferred neutrality dressed as universality. His music refused that disguise. Every performance was an indictment, every album a record of dissent, every lyric a confrontation with power. Western award systems historically separated art from politics, even when that separation was artificial.

During Fela’s lifetime, his work challenged military regimes, foreign interference, economic exploitation, and cultural self denial. These themes did not translate neatly into award show narratives that favored romance, celebration, and personal triumph. The Grammys, like many global institutions, were structured to reward polish more than provocation.

African music in that era was often treated as ethnographic rather than contemporary. It was studied, archived, admired from a distance, but rarely placed on the same pedestal as Western pop innovation. Fela was not interested in being a cultural exhibit. He positioned himself as a modern revolutionary using sound as his weapon.

This tension made him difficult to honor within a system that required consensus. Honouring Fela meant endorsing discomfort. It meant recognizing that some of the most influential music of the twentieth century came wrapped in anger, resistance, and unapologetic African identity.

Afrobeat Without Institutional Permission

Afrobeat did not wait for approval. It expanded without invitations, passports, or validation. From Lagos to London to New York, musicians absorbed its rhythms, its structure, and its political courage. Hip hop artists borrowed its defiance. Jazz musicians studied its complexity. Funk musicians recognized its groove.

Despite this influence, Afrobeat remained largely absent from major award narratives. It existed as an influence rather than a category. This invisibility was not accidental. Award institutions often follow commercial infrastructure, and Afrobeat was never built for Western charts. It was built for communal experience, live performance, and social awakening.

Fela’s refusal to compromise also limited institutional access. He did not campaign for awards, attend industry mixers, or tailor his work for global palatability. His music was long, repetitive, demanding, and deeply local. These qualities later became strengths, but at the time they were barriers.

By the time the global music industry began celebrating African sounds openly, Fela had already become a reference point rather than a participant. His influence was everywhere, yet his name often appeared as history rather than headline.

The Grammys and Their Slow Evolution

The Recording Academy has changed, but slowly. For much of its history, it reflected the cultural blind spots of the industry it represented. Global music was acknowledged in fragments rather than embraced fully. African artists were underrepresented, undercategorized, and often misunderstood.

It took decades for the Grammys to expand beyond Western dominant frameworks. New categories emerged, voting bodies diversified, and conversations about inclusion grew louder. These changes did not happen in isolation. They were responses to shifting global power in music consumption and production.

As African artists began dominating international charts, touring globally, and influencing mainstream sound, institutions were forced to adapt. Afrobeat and Afrobeats became impossible to ignore. Yet even then, the conversation often centered on contemporary stars rather than foundational figures.

Honouring Fela now reflects this evolution. It is not just about acknowledging one artist. It is about acknowledging a system that took too long to recognize where modern global music truly began.

The Weight of Posthumous Recognition

Posthumous awards carry a unique burden. They are acts of correction rather than celebration. They acknowledge influence while admitting absence. In Fela’s case, the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award serves as an institutional confession that greatness was recognized late but unmistakably.

Fela never sought validation from Western institutions, but his absence from their records mattered symbolically. Recognition shapes archives, curricula, and cultural memory. Without it, future generations risk encountering incomplete histories of music innovation.

This award does not change Fela’s legacy, but it reframes it within official global history. It places Afrobeat not on the margins, but at the center of modern musical development. It affirms that political music, African music, and uncompromising art deserve the same reverence as commercial success.

The timing matters. Nearly thirty years after his death, the award arrives in a world finally ready to understand what Fela was saying all along.

Zombie and the Turning Point of Institutional Memory

The induction of Zombie into the Grammy Hall of Fame in 2025 marked a quiet shift. It was not flashy, but it was foundational. The Hall of Fame recognizes recordings of lasting historical significance, not popularity. Zombie fit that definition perfectly.

The album remains one of the most fearless musical critiques of military power ever recorded. Its relevance has not diminished. Instead, it has expanded, finding resonance in new political contexts across the globe. Its inclusion signaled that the Recording Academy had begun reassessing its own archive.

Zombie forced a reconsideration of what qualifies as canonical music. It challenged the idea that global influence must be mediated through Western success. It argued that impact, endurance, and courage matter more than chart position.

Once Zombie entered the archive, Fela’s absence from lifetime recognition became increasingly indefensible.

Why Now Became Inevitable

The decision to honour Fela in 2026 did not emerge suddenly. It is the product of years of cultural pressure, academic reassessment, and generational change within the music industry. Younger voters grew up with Fela as a reference, not a relic.

African music now occupies global center stage. Streaming platforms flattened access. Audiences demanded authenticity. Protest music regained relevance. In this environment, Fela’s work felt prophetic rather than historical.

The Grammys could no longer tell the story of modern music without acknowledging him formally. Doing so earlier might have been radical. Doing so now is necessary.

This honour represents an alignment between influence and institution that was long overdue.

What This Honour Truly Represents

The Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award is not a trophy. It is a recalibration. It acknowledges that music history is incomplete without African pioneers at its core. It validates political music as legitimate art. It recognizes that global culture does not flow in one direction.

For African artists, the honour carries symbolic weight. It confirms that global institutions can evolve, even if slowly. It suggests that legacy is not erased by delay, only deferred.

For Fela, the award changes nothing and everything. His music remains as confrontational as ever. His message remains unresolved. But his place in official history is now sealed.

The Grammys did not give Fela immortality. They finally acknowledged it.

Discussion about this post