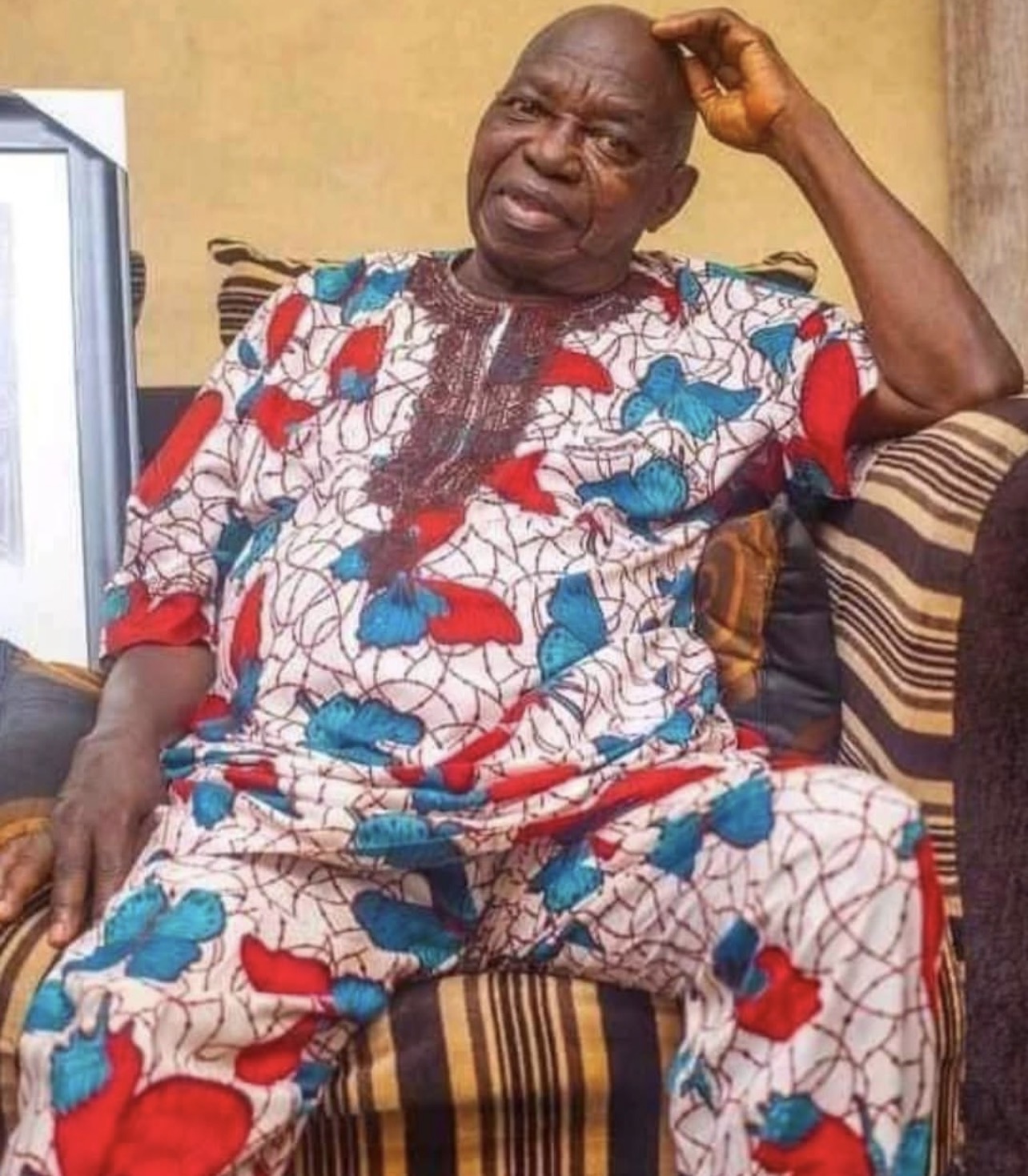

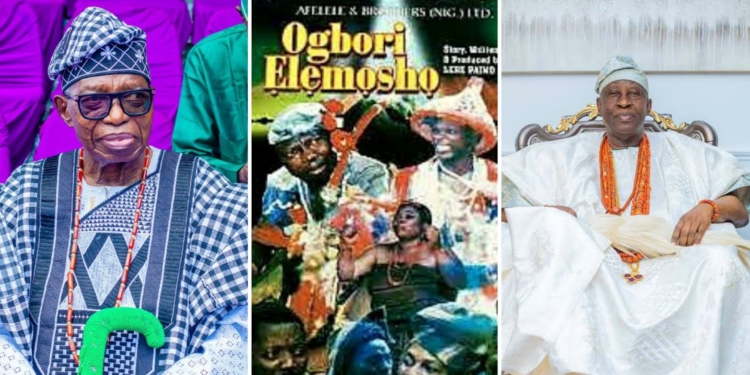

For more than six decades, Chief Olalere Osunpaimo (MFR), famously known as Lere Paimo and revered by fans as Eda Onile Ola, has stood as one of the most recognisable pillars of Yoruba theatre and film.

His work helped define historical storytelling in Nigerian cinema, with Ogbori Elemoso emerging as one of the most iconic productions of that era. He became popular following a lead role as Soun Ogunola played in an epic yoruba film titled Ogbori Elemoso which brought him into limelight.

But in late 2025, the veteran actor found himself at the centre of a bitter controversy. It was about an alleged attempt to remake Ogbori Elemoso without his consent, triggering a public outcry, legal threats, palace rebuttals, and a wider debate about intellectual property versus communal history.

Why Ogbori Elemoso Matters

Ogbori Elemoso is not merely a film title; it represents a cornerstone of Yoruba historical cinema, dramatising the life of Soun Ogunlola, the legendary founder and first king of Ogbomoso.

According to Paimo, producing the original film decades ago came at enormous personal cost. He said:

“I went into debt. I lost my car while making this film. This work was meant to be my legacy and a benefit for my children and me.”

To him, the film is both creative property and personal inheritance, a point that would later fuel his resistance to any remake he did not authorise.

Lere Paimo’s version of the epic film is slightly different from the history and origins of Ogbori Elemoso.

A Brief History of Ogunlola and the Origins of Ogbori Elemoso

Historical accounts trace the origins of Ògbómọ̀ṣọ́ to around 1650, when Ogunlola, a hunter, migrated to the area in pursuit of his hunting career. He arrived at the site, which was then a dense forest, with his wife Esuu, and they initially camped beneath an Ajagbon tree, which still stands today near the Soun’s palace. The couple later built a hut close to the tree and settled there permanently.

After settling in the forest, Ogunlola noticed smoke rising daily from nearby locations. Curious, he investigated and discovered that four other hunters were also living in the jungle. These included Aale, a Nupe elephant hunter who settled at what is now known as Oke-Elerin; Onisile, an Otta prince who left his hometown following a title dispute and settled at Ijeru; Orisatolu, who camped at Isapa; and another hunter who lived at Akande, a settlement that no longer exists.

Ogunlola gradually established dominance among the hunters, aided by his exceptional hunting skills and the influence of his wife, Esuu, who was renowned for producing tobacco snuff and guinea corn wine that the hunters favoured. Together, they formed a hunters’ association known as Alango, created to protect the settlement from slave raiders, hunt collectively and support one another.

As more people migrated into the area, the settlement expanded into a village. Ogunlola emerged as its leader, with his hut serving as both an administrative centre and a court where disputes were resolved.

According to Ogbomoso history, Ogunlola was later imprisoned at Oyo-Ile, the capital of the old Oyo Empire, over an alleged offence linked to his wife, Lorungbenkun. While in prison, he learned of a fearsome warrior named Elemosho, who had been terrorising Oyo-Ile.

Ogunlola appealed to the Alaafin of Oyo to grant him temporary freedom to confront Elemoso. After repeated pleas, permission was granted. Elemoso was reputed to be a powerful and nearly invincible warrior who fought with swords and arrows. Ogunlola studied his movements for several days before launching a surprise attack at night, killing Elemoso with an arrow. He beheaded him and presented the head to the Alaafin.

Pleased with the feat, the Alaafin granted Ogunlola his freedom and urged him to remain in Oyo-Ile. Ogunlola declined, reportedly saying, “Ejé kí á ma se óhún” (I.e: “Let me stay far away in my land”). From this expression emerged the title Sọ̀ún, which Ogunlola later assumed upon returning home as the first Sọ̀ún of Ògbómọ̀ṣọ́.

The settlement became known as “Eni ti Ogbori Elemoso” (I.e: “the one who carried Elemosho’s head”). This was later shortened to Ogbori Elemoso, and eventually Ògbómọ̀ṣọ́, the name the town bears today. From its beginnings as a small hunters’ settlement, Ògbómọ̀ṣọ́ grew into a prominent town, shaped by Ogunlola’s leadership and its role in Yoruba history.

How the Controversy Began

October 2025: An Unexpected Visit and a Surprise Payment

In October 2025, Lere Paimo said he was visited at his home by individuals linked to Fewchore Studios, including a film practitioner identified as Ben Ayoola (popularly known as Ben O Ben).

According to Paimo, they told him bluntly that:

“They did not need my consent to remake Ogbori Elemosho and that they only came to give me a ‘gift’ for the work.”

Shortly after the visit, ₦7.5 million was paid into his bank account.

Paimo said the payment immediately raised alarm, and not excitement, especially after consulting his children. He continued:

“My children described it as coercive and manipulation. Acting on their advice, I immediately returned the money.”

Following this, his lawyer issued a cease-and-desist letter, warning against proceeding with any remake or related production without his consent.

December 17, 2025: Lere Paimo Goes Public

At a press conference in Ibadan, Lere Paimo formally took his grievances to the public.

He alleged that the planned production had the backing of the Soun of Ogbomosoland, Oba Ghandi Afolabi Olaoye, and that he was told resistance would be futile. He claimed:

“They told me they already had permission from the Soun of Ogbomoso and that my consent was no longer required.”

He further alleged intimidation:

“They even said that if I went to court, I would not get justice.”

The veteran actor described the experience as an attempt to strip him of control over his own work, particularly at a vulnerable stage of life.

Lere Paimo added that his decision to speak publicly was driven by fear for himself and the precedent such actions could set. His concerns included:

• Loss of economic benefit from a work he originated

• Disrespect for authorship and consent

• Exploitation of age and influence imbalance

• Erasure of a creator’s ownership under the guise of culture

He appealed directly to Oyo State Governor , Seyi Makinde, Pastor Enoch Adeboye, security agencies, and prominent sons and daughters of Ogbomoso to intervene, saying:

“Powerful people are trying to take away what I laboured for.”

Fewchore Studios Responds: ‘This Is Not a Remake’

On Wednesday, Aniekan Equere representing Fewchore Studios issued a detailed statement denying any wrongdoing. The studio insisted that:

“Ogbori Elemoso refers to Soun Ogunlola, the founder and first king of Ogbomoso.”

Under Nigerian and international copyright law, historical facts, titles and folklore are in the public domain and may be creatively interpreted, provided no one copies another person’s specific literary or cinematographic expression.”

“No individual can lawfully claim exclusive ownership over the history of a town or its founding monarch.

“We have not remade or reproduced any film, script, or creative work by Chief Olalere Osunpaimo, nor used any of his proprietary materials.

“The project is an original historical film developed from independent research.”

On the financial aspect, the studio clarified:

“A meeting resulted in his request for ₦30 million. We offered ₦15 million as a goodwill gesture, and ₦7.5 million was paid as an initial instalment, clearly stated to be a gift, not payment for rights.”

They added that there is:

“No registered copyright or trademark in the name Ogbori Elemoso in favour of Chief Osunpaimo at the Nigerian Copyright Commission.”

The Palace Weighs In: ‘History Belongs to Ogbomoso’

The palace of the Soun of Ogbomosoland also issued a clarification, signed by the monarch’s media aide, Peter Olaleye. It distanced the palace from what it described as “misleading allegations” credited to Mr Paimo. It rejected the claim that it authorised an illegal remake.

The palace stated that the story belongs to Ogbomoso, and the one they are making now is a new story entirely.

It maintained that the production aims to tell the broader historical account of Ogbomoso, not reproduce Paimo’s film.

According to the palace, the Soun had earlier engaged Lere Paimo and informed him of plans to support a creative retelling of Ogbomoso’s history in line with modern global storytelling standards, including platforms such as Netflix.

The invitation was to participate in the project as an actor and contributor, not as a rights holder to the town’s history. The palace said:

“The financial offer made to him was strictly for his participation as an actor and contributor, not for the purchase of any copyright.”

The palace further clarified that the film currently in production bears a different title, a distinct and expanded storyline, and a separate plot structure, despite drawing inspiration from Ogbomoso’s history.

While acknowledging that Mr Paimo had shared his version of the Ogbori Elemoso story during earlier engagements, the palace said the forthcoming film, scheduled for release next year, is not an exclusive retelling of any individual’s account but an original creative production.

The Legal Grey Area: Copyright vs Cultural History

At the heart of the dispute lies a complex question. The question is if a filmmaker can own exclusive rights to a historical narrative rooted in communal tradition?

Fewchore Studios argues that history and folklore are public domain, while Paimo insists that his specific cinematic expression, structure, and legacy deserve protection.

While professional bodies like the Association of Nigeria Theatre Arts Practitioners (ANTP) have clarified that recent rumours of Paimo’s death were false, they have yet to issue a formal position on the remake dispute itself.

Still, the controversy has reignited long-standing concerns within Nollywood:

• How are veteran creatives protected?

• Where does tradition end and authorship begin?

• Who benefits when old stories find new commercial life?

Conclusion: A Fight Bigger Than One Film

For Lere Paimo, this is not simply about a movie remake, but one about dignity, ownership, and legacy.

For producers and traditional institutions, it is about cultural storytelling and historical continuity.

As the debate continues, Ogbori Elemoso has once again become a powerful symbol of history and of unresolved tension between creative labour and communal heritage in Nigerian cinema.

Discussion about this post