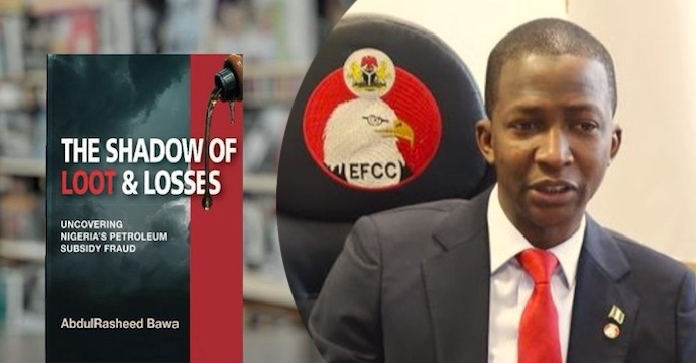

Trillions of naira reportedly vanished silently under the radar of institutions that were supposed to protect them. Nigeria’s petroleum subsidy, a lifeline meant to keep fuel accessible, became a labyrinth of deception where the powerful manipulated the system with precision. In his new book, The Shadow of Loot & Losses, Ex-EFCC Boss Abdulrasheed Bawa exposes the intricate networks that turned a national program into a personal treasure trove for a few.

The revelations shared in 2026 do not merely point fingers at faceless entities; they pierce the veil of secrecy and implicate a system that tolerated fraud as routine. Reading the book is like walking through a house of mirrors where every reflection reveals another layer of complicity, and the national cost is almost unimaginable.

Bawa’s tenure at the EFCC, brief yet impactful, gives him a vantage point few could claim. He did not merely oversee investigations from afar; he led operations that attempted to unearth the rot buried in official documents, bank accounts, and shipping manifests.

The book arrives at a delicate moment in national discourse, where economic policy, corruption, and political alignment intersect. The narrative of subsidy fraud, as presented by Bawa, reads like an intricate investigation but unfolds with the literary tension of a thriller. Every page draws attention to the interplay between human greed, regulatory gaps, and the structures that allowed billions to disappear unnoticed.

For readers, the suspense is not in who committed the fraud but in how deeply the tentacles of corruption reached and the systems that failed to stop it. Bawa’s book transforms abstract numbers into a story of consequences, a narrative where national wealth became collateral damage in a sophisticated scheme.

Systemic Deception: Ghost Imports and Phantom Fuel

Nigeria’s fuel subsidy was never intended to be a story of loss but the systems Bawa exposes suggest it became a theater of orchestrated deception. Ghost importing was the foundation of much of the fraud, where subsidies were claimed for fuel that never crossed Nigerian waters. In his book, Bawa details the meticulous planning behind these schemes, where shipping manifests were forged, and logistics companies were complicit in creating documentation that could deceive even experienced auditors. These operations were not spontaneous; they were highly coordinated, exploiting every regulatory gap and every weak link in government oversight.

Bawa’s account shows that ghost imports were often coupled with over-invoicing strategies, creating a double layer of financial manipulation. By inflating shipment volumes or prices, perpetrators could extract subsidies far beyond what was legitimately due. Every transaction was cloaked in layers of falsified paperwork, each designed to withstand cursory scrutiny. What is most unsettling is the scale; trillions of naira were lost, quietly siphoned through systems that should have detected irregularities long before they escalated.

Forged shipping documents and bills of lading formed another pillar of the fraud, enabling fraudsters to present seemingly legitimate claims to the federal government. Bawa emphasizes that these documents were not amateurish; they mimicked official formats, carried logos and stamps that appeared authentic, and were backed by networks that understood the mechanics of government auditing. The sophistication of these operations reveals both the ingenuity of the perpetrators and the vulnerabilities of Nigeria’s administrative systems.

The consequences of these phantom shipments were not abstract numbers. Fuel meant for domestic distribution was often diverted into black markets, sometimes across borders, amplifying scarcity and inflating prices for everyday Nigerians. Bawa’s narrative brings a human dimension to the scandal, showing that behind the accounting ledgers, national welfare and public trust were quietly eroded. The ghost imports were ghosts not only of fuel but of lost confidence in institutions that promised protection but delivered oversight only in name.

Over-Invoicing and the Architecture of Collusion

Over-invoicing emerges in Bawa’s book as more than a financial tactic; it was an architecture of collusion. Private sector actors and government officials, according to his investigation, often operated in tacit partnerships that converted subsidy programs into personal profit machines. By inflating shipment prices, multiple actors could claim the same funds repeatedly, a technique that transformed legitimate infrastructure into a conduit for illicit enrichment.

Bawa describes the psychological dimension of this fraud as well. Participants were not merely opportunistic; they operated in an ecosystem where deceit was normalized, and compliance officers were either complicit or powerless to intervene. The book explores how cultural tolerance for corruption, institutional weaknesses, and individual ambition intertwined, creating fertile ground for sustained over-invoicing. Fraud became a predictable outcome rather than an exception, a systemic flaw rather than a moral lapse by a few.

The ripple effects of over-invoicing extended beyond the federal treasury. Investors, traders, and logistics companies all adapted to the distorted economic signals created by inflated prices. The market for fuel became opaque, where legitimate demand signals were replaced by manipulated invoices, making planning and forecasting almost impossible. Bawa’s insights illustrate the broader economic cost of these schemes, showing that billions lost were not just administrative failures but catalysts for inefficiency and instability in the energy sector.

Bawa also stresses the difficulty of enforcement in this environment. Investigators often confronted legal ambiguities, jurisdictional challenges, and strategic concealment. His recounting of the investigative process, the hours spent tracing documentation, interviewing witnesses, and navigating bureaucratic resistance, makes clear that over-invoicing was not just a crime of numbers but a contest of institutional stamina. The book portrays this as a battle between the meticulous craft of fraudsters and the increasingly fragile capacity of oversight bodies.

Forged Documents and the Currency of Deception

Central to Bawa’s exposé is the role of forged documents in perpetuating subsidy fraud. Bills of lading, shipping manifests, and internal approvals were routinely falsified to present a veneer of legitimacy. What appears on paper rarely reflected reality, and Bawa demonstrates the ingenuity required to construct forgeries that could pass through multiple layers of review. The book captures the tension between deception and detection, showing the sophistication required to mislead even seasoned officials.

Forged documents were not merely a means to an end but a symbol of systemic vulnerability. Bawa reveals how easy it was to exploit the gaps between departments, regulatory bodies, and ministries. By presenting convincingly fraudulent records, perpetrators could maintain a façade of legality while extracting enormous sums from the treasury. The book frames this as a shadow economy operating in plain sight, where the paper trail was both evidence and illusion.

The narrative further explores the complicity of intermediaries, from clerks to logistics companies, whose cooperation or indifference allowed forged records to thrive. Bawa’s account is meticulous, tracing the life of a single falsified document through layers of verification that ultimately failed. This system of checks and balances, Bawa argues, was never designed to confront intentional deception on such a scale, making the fraud almost inevitable once initiated.

Bawa’s reflections extend to the ethical dimensions of document forgery. Beyond financial loss, these manipulations eroded public trust in the government and in the institutions meant to safeguard national resources. The book positions each forged bill not only as evidence of fraud but as a testament to how institutional culture, weak enforcement, and human ambition combined to create a long-running national scandal.

Diversion, Smuggling, and the Black Market Economy

Diversion and smuggling are presented in Bawa’s book as the final stage in the extraction of illicit profit. Fuel subsidized for domestic consumption often disappeared into black markets, crossing borders or entering informal trade channels. Bawa’s account reveals how structured these operations were, with networks that coordinated logistics, financing, and distribution to maximize returns. What might appear as random theft is, in reality, a carefully orchestrated system with predictable outcomes and vast economic consequences.

Bawa details the consequences for the domestic market, where artificial scarcity drives prices up and ordinary citizens bear the cost. Smuggling did not merely deprive the treasury; it destabilized supply chains, created artificial shortages, and injected volatility into a critical sector. The book emphasizes that these outcomes were foreseeable yet tolerated, a symptom of regulatory complacency and the limits of enforcement capacity.

The scale of these operations, according to Bawa, implicates multiple layers of governance. Officials who were supposed to oversee distribution often turned a blind eye or actively facilitated diversion. Bawa’s narrative paints a picture of complicity that spans government agencies, private companies, and even transport operators, showing how multi-trillion naira fraud became almost routine in a context of normalized corruption.

Bawa also reflects on the investigative challenges these operations presented. Tracking fuel through informal channels, identifying actors, and proving complicity required unprecedented coordination. The book presents these cases not just as anecdotal, but as a comprehensive exposé of systems exploited, lessons learned, and limitations encountered, making the narrative both a revelation and a call to action.

Economic Implications and Policy Lessons

Bawa’s analysis extends beyond fraud to its economic consequences. Trillions of naira lost to ghost imports, over-invoicing, and smuggling represent not just administrative failure but a drain on Nigeria’s fiscal capacity. The book explores how these losses ripple through public spending, infrastructure projects, and social welfare programs, demonstrating that corruption is both a moral and an economic hazard.

The Ex-EFCC boss detailed how manipulated subsidy programs distorted market signals, creating inefficiencies that affected fuel pricing, distribution logistics, and private sector planning. Investors and businesses operating under artificially inflated costs faced uncertainty, while citizens bore the burden of scarcity and price volatility. Bawa’s book portrays these outcomes as the predictable consequences of systemic neglect, rather than random misfortune, illustrating the tangible impact of abstract fiscal manipulation.

Policy lessons are embedded in every chapter. Bawa advocates for stronger regulatory oversight, technological monitoring, and transparent auditing processes, emphasizing that reform must address both individual behavior and institutional design. The book frames these recommendations as pragmatic rather than idealistic, grounded in the realities of enforcement and governance. The narrative balances revelation with prescription, providing readers with insights that extend beyond scandal into actionable governance strategies.

Bawa also emphasizes the importance of accountability and deterrence. Without mechanisms to enforce consequences for both private actors and public officials, the cycle of fraud will likely repeat. The book underscores that reform requires a holistic approach, combining legal rigor, political will, and ethical commitment to reshape the institutions managing Nigeria’s most critical resources.

Conclusion: Shadows, Choices, and Consequences

Bawa’s book paints a portrait of a system stretched thin by ambition, greed, and neglect. It shows how human choices, when unchecked, can ripple through institutions and society, turning programs meant to serve millions into tools for private gain. The shadows he uncovers are not only financial but moral, reflecting the cost of tolerance for wrongdoing.

The revelations compel reflection on collective responsibility. Citizens, leaders, and institutions all play a part in shaping the environment where corruption either thrives or is constrained. The book suggests that reform is not simply about rules or audits but about cultivating a culture that values accountability and transparency at every level.

The Shadow of Loot & Losses leaves a lingering question for Nigeria: how long will the nation allow hidden networks to dictate the fate of public resources, and what will it take to reclaim trust, fairness, and integrity in systems that affect every citizen? Bawa’s account serves as both a warning and a prompt to confront these enduring challenges.

Discussion about this post