No one remembers hearing a gunshot first—only the roar of fire. In February 1897, Benin City’s heart began to collapse inward. The coral-beaded corridors that once glowed with incense and drumming went silent, except for the hiss of torches turning royal wood to ash. Somewhere deep in the labyrinth of courtyards, Oba Ovonramwen Nogbaisi sat still, surrounded by priests who could do nothing but whisper prayers that the ancestors might intervene. Outside, British marines moved through the compound like men who had forgotten the difference between war and plunder.

When dawn came, the empire’s soldiers gathered what they could not understand: bronze heads with eyes that did not blink, ivory tusks carved in quiet defiance, altarpieces heavy with centuries of spirit. They called them “artifacts.” The Benin people called them ancestral breath. Each piece was a vessel, carrying not just metal but the pulse of the kingdom’s memory.

By the time the smoke cleared, the Oba’s throne room was empty. A kingdom built on ritual precision had been broken open by force. To the British, the loot was spoils of victory. To the Benin royal court, it was the start of a lingering curse—an unending disquiet that would follow whoever dared to own what was never meant to be possessed.

And though the world would come to call them “the Benin Bronzes,” no one has yet agreed on what followed them home.

The Kingdom That Spoke Through Metal

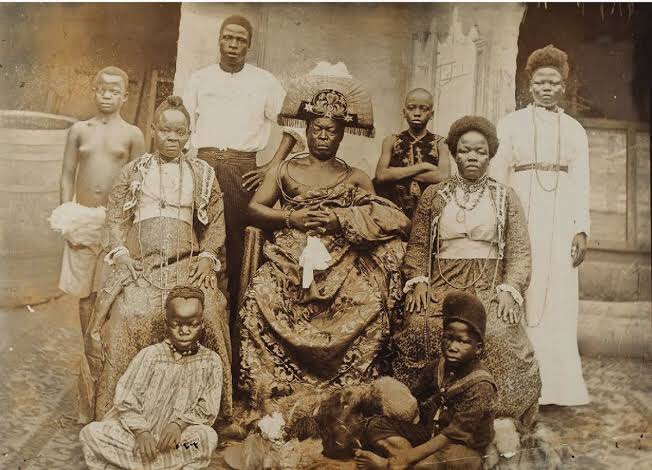

Before the looting, Benin was not merely a city but an order—a precise machinery of power, ritual, and artistry. For nearly five centuries, its Obas commissioned bronze casters from the Igun-Eronmwon guild to document royal events, victories, and ancestral successions. The artisans were both historians and priests; every molten casting was a prayer that memory would never decay.

The bronzes were never decorative. Each head, plaque, or vessel was installed at an ancestral altar, linking the reigning Oba to his forebears. In Benin cosmology, to remove a piece from its shrine was to cut the cord that tethered the living to the dead. Every object carried a charge—the weight of continuity and duty.

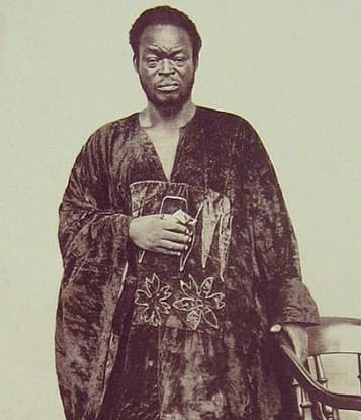

Ovonramwen Nogbaisi inherited this sacred order in 1888, at a time when Britain’s Royal Niger Company was tightening its grip on West Africa’s trade routes. He was the 36th Oba in an unbroken lineage that dated back to Oranmiyan, the semi-divine founder who bridged Yoruba and Edo dynasties. The Oba’s palace—an immense sprawl of courtyards, shrines, and wooden pillars—was both the kingdom’s archive and its conscience.

To understand why the bronzes mattered is to see them as living witnesses. Each face sculpted in brass was not merely likeness but authority, representing the unbroken chain of kingship. When the British destroyed the palace and scattered those faces, they did not just loot art—they disrupted a conversation between the living and the dead.

The Expedition That Became a Reckoning

The event that led to the looting began with a diplomatic ambush. In early 1897, a British vice-consul, James Phillips, marched toward Benin City against explicit warnings that a sacred festival was underway and no foreigners could enter. His expedition, armed under the guise of diplomacy, was attacked near Ughoton; almost every Briton in the party was killed.

London called it a “massacre.” The empire demanded retribution. Within weeks, a punitive force of about 1,200 soldiers—commanded by Admiral Harry Rawson—was dispatched from the Cape. Their mission was simple: capture the Oba, burn the city, and secure the trade routes.

When Rawson’s troops reached Benin City, they found resistance but not enough to match imperial firepower. The royal palace, centuries old, was torched. Thousands of objects were seized—bronzes, ivories, ceremonial swords, coral crowns. Some soldiers auctioned them privately on the voyage home; others handed them to museums in London and Berlin.

Oba Ovonramwen fled but later surrendered, offering himself to prevent further destruction. The British exiled him to Calabar, where he lived in quiet captivity until his death in 1914. For the Benin people, his exile marked not just the fall of a king but the silence of an entire spiritual system.

In oral histories, elders began to say that the spirits bound to those bronzes would wander restless until they returned home. Whether metaphor or warning, that belief seeded a narrative of retribution—a curse that history would one day have to reckon with.

The Curse That Crossed the Sea

The first signs of unease were whispered among British sailors. A few days after the looting, one vessel carrying bronzes reportedly encountered violent storms in unusually calm waters. Several men were said to have fallen ill. Colonial officers, steeped in rationalism, dismissed it as coincidence. But stories of bad luck—broken marriages, sudden deaths, strange fires—followed some of those who trafficked the bronzes in the early twentieth century.

In Benin oral tradition, these tales became proof that the spirits of the ancestors had refused relocation. The artefacts were sacred because they contained ase—vital spiritual force. In moving them, the looters carried fragments of that force across oceans. And like any power unanchored from its shrine, it sought balance.

By the 1920s, collectors in London and Berlin spoke of uncanny misfortunes—bankruptcies, museum fires, untraceable thefts. In 1939, during the Blitz, several storerooms holding Benin artefacts were destroyed by German bombs. Edo storytellers later described it as the ancestors reclaiming their breath through fire.

There was never scientific evidence of a literal curse. Yet even today, curators admit to a kind of unease. Handling the bronzes, they say, feels different. The metal seems almost warm, charged. Perhaps that’s imagination—or perhaps, as one Edo proverb says, “What is removed from its altar still remembers its home.”

The Long Silence of Ovonramwen

Exiled to Calabar, Ovonramwen’s life was stripped of ceremony. The man who once presided over rituals older than many empires spent his final years by a riverbank, far from the sound of Benin drums. Colonial officials described him as “gentle, melancholic, resigned.” Yet even in defeat, he carried himself like one who knew time was circular—that empires, too, could one day be humbled.

He left no recorded speeches, but local accounts remember his final words as a quiet invocation that Benin’s spirit would “rise when iron forgets arrogance.” When he died in 1914, British officers refused a royal burial, fearing it might spark rebellion. His body was interred in secret. But his story did not end in silence; it became the origin of a cultural haunting.

Across decades, the name Ovonramwen became synonymous with loss and endurance. To Edo people, his exile symbolized the theft of their spiritual center. Every missing bronze was a fragment of his voice scattered to foreign winds. To possess those bronzes, they said, was to inherit the sorrow of the man whose world they came from.

Europe’s Guilt, Africa’s Memory

By the mid-20th century, the Benin Bronzes had become prized exhibits in Western museums—the British Museum, Berlin’s Ethnological Museum, and countless private collections. Their catalogues spoke of “exceptional craftsmanship,” yet rarely mentioned the fire that forged their exile.

As Nigeria approached independence in 1960, calls for restitution began to rise. Benin’s new monarchs, successors of Ovonramwen, petitioned Britain for return of their ancestral treasures. Each time, they met bureaucratic deflection—claims that the bronzes were “safer” abroad, or that returning them would “set a precedent.”

But history’s weight has a long memory. From the 1970s onward, each global debate on cultural restitution seemed to echo the same moral undercurrent: the bronzes were not just property—they were testimony. And perhaps the curse was never supernatural at all. Perhaps it was the quiet erosion of legitimacy that clung to every institution built on stolen meaning.

When Germany announced in 2021 that it would return hundreds of Benin Bronzes, many Edo people described the gesture not as charity but as prophecy fulfilled. The ancestors, they said, were finally tired of wandering.

The Return and the Reckoning

In 2022, crates began to arrive in Nigeria from Berlin and London. Each contained a fragment of Benin’s lost breath—bronze heads, plaques, ceremonial reliefs. When Oba Ewuare II of Benin received the first batch, he stood in silence before the crates, dressed in coral red. “They have come home,” he said, almost in whisper.

That homecoming was not without controversy. Some pieces were handed to Nigeria’s federal government rather than the Benin Palace, reigniting old questions of ownership: does restitution belong to the nation or the kingdom that birthed it? Yet beyond politics, there was symbolism—the slow unbinding of a curse.

Inside Benin City, elders organized quiet libations, invoking Ovonramwen’s name. For them, the bronzes’ return was not just cultural justice but spiritual closure. After 125 years, the conversation between ancestors and descendants could resume.

The Curse as Conscience

If there was ever a curse, perhaps it was this: that those who saw art where others saw ancestry would never know peace until they restored what they took. Across museums, curators now face uncomfortable questions about provenance, ethics, and colonial violence. Each plaque gleams beautifully under museum light but carries the shadow of how it left home.

Benin’s story reminds the world that cultural theft is not erased by time. The curse is moral fatigue—the haunting of institutions that mistake possession for understanding. It is the burden of knowing that a piece of beauty might also be a piece of someone’s grief.

For the Edo people, the lesson endures: memory cannot be colonized. Metal may travel, but meaning waits. The bronzes, forged in fire and spirit, were always meant to outlast arrogance.

Closing Reflection– When Iron Remembers Its Maker

The story of Oba Ovonramwen’s bronzes is not just about art or empire. It is about what happens when power misreads the sacred as merchandise. The curse, if one must name it, lies in the echo that follows every act of forgetting—the slow, relentless return of truth.

Today, as more bronzes come home, Benin’s palace is alive again with the sound of hammer and chant. New casters melt old metal, breathing continuity into silence. Somewhere in that rhythm, one might imagine the old Oba listening, unbroken, finally vindicated.

The bronzes were always more than treasure. They were conversation. And conversations, once interrupted, have a way of resuming—sometimes as history, sometimes as justice, sometimes as the quiet, enduring memory of a curse fulfilled.

Discussion about this post