Calabar begins where the river remembers. Each dawn, the Cross River drags light across its surface like a slow forgiveness, folding yesterday into another humid day. Along its banks, the old quarters breathe with secrets — timbers warped by rain, balconies heavy with vines, doors that still open inward to whispers. The air smells of palm oil, sea salt, and stories that refuse to end.

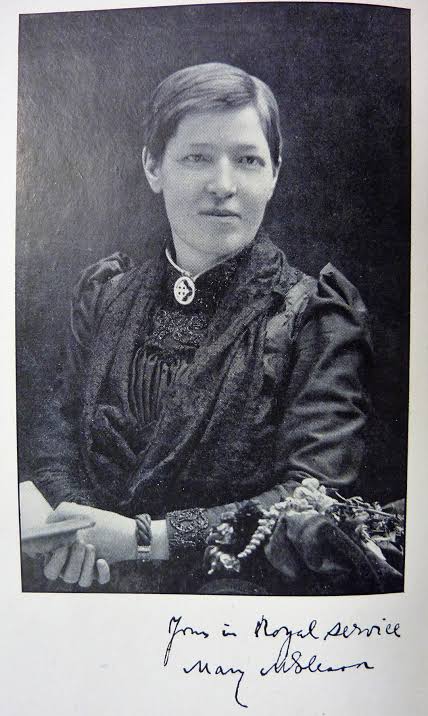

Among these streets, there lingers the trace of a woman — not in statues or stone, but in the way silence falls when her name is spoken. Her face lives in faded portraits, her voice in letters that never meant to outlive her.

She came from across the sea, small in stature but enormous in defiance, carrying a lamp that seemed far too fragile for the storm that awaited her. Yet the river remembers the way she crossed it — not as a conqueror, but as someone who dared to listen.

Her name was Mary Slessor, a weaver’s daughter from the grey spine of Scotland who found herself at the edge of Africa’s green flame. She came to Calabar when the city was a breathing paradox — torn between empire and tradition, gospel and gunpowder, redemption and resistance. What she met there would test the meaning of faith, and what she left behind would change how the land remembered mercy.

Even now, when night thickens and the tide turns slow beneath the bridge, the walls of the old quarters still lean toward one another, whispering her name like a prayer that never found its amen.

This is not just history.

This is a story — of a woman, a city, betrayal and the silence that binds them still.

The Arrival

The ship from Liverpool reached the Bight of Bonny under a pale sun. The air was heavy, thick with the scent of salt, palm oil, and smoke. The young missionary leaned over the rail and saw, not the paradise of her imagination, but a land trembling with life — too vast, too wild, too loud. Around her, men in loose shirts shouted orders; Efik traders in white robes moved cargo between canoes and shore.

Mary Mitchell Slessor arrived in Calabar in 1876, small, fiery-haired, with a stubborn heart and a Bible that seemed too heavy for her hands.

Calabar in 1876 was a crossroads of the old and the new — where the slave trade had ended in law but not in memory, and the British flag flapped like a warning.

Mary Slessor was twenty-eight, fragile in body but unyielding in spirit. Born in Aberdeen’s factory slums, she had known hunger, hardship, and a drunk father who beat faith into silence. The mission board had doubted her — too poor, too plain, too untrained. But she had a will like tempered steel. She came to teach, to heal, to preach. Yet what she found first was fever. Within weeks of arrival, her fellow missionaries fell sick. The humid air clung to her skin; her eyes grew hollow from sleepless nights at Duke Town. Still, she wrote home that she was “not afraid to die, but afraid to waste.”

The locals called her Eka Kpukpru Owo — “Mother of All the People.” But before she earned that name, she learned to live as one of them. She sat with market women in the evenings, watched children play with carved wooden toys, and listened to the elders tell stories of gods, twins, and spirits that walked the forest. Slowly, the missionary became something more dangerous: not an outsider preaching from a pulpit, but a listener who began to understand.

The Twins’ Silence

There are truths the land buries until it meets the right heart. Among the Efik and the Okoyong, it was believed that twins were a curse — one child human, the other from the spirit world. When twins were born, they were taken into the forest and left to die. The mothers were shunned, marked as impure. No British decree could change this, because it was not a law of man, but a covenant of fear.

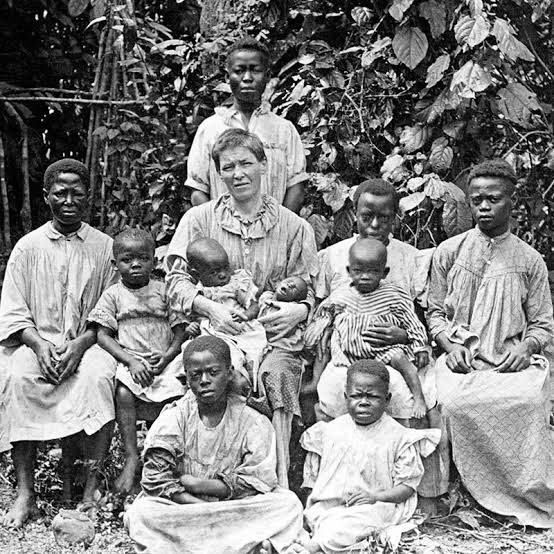

It was Mary who broke the silence. The first time she found twin infants abandoned near a hut in Old Town, she wrapped them in her shawl and carried them to her room. She washed them, fed them, and sat through the night singing to them in Efik. Her neighbours thought her mad — a woman who dared invite spirits into her home. But she persisted. When the mothers refused to take the children back, she raised them herself. Soon her small mud house was filled with crying babies, and her mat was never dry.

Word spread — of the white woman who kept cursed children and lived. Chiefs sent messengers to watch her, to see if her house would collapse. When it did not, curiosity turned to awe. It was not sermons that ended the killings; it was witness. Mary did not preach — she proved. Within years, she had saved dozens of children, and her example began to ripple through the villages. Still, her courage came at a cost. She was marked by both worlds: distrusted by some locals, dismissed by colonial men who thought her sentimental.

She called the babies “my bairns.” They, in turn, called her Eka Kpukpru Owo — Mother of All.

Okoyong: Where Faith Met Fury

In 1888, she moved deeper inland, into the heart of Okoyong — a territory feared even by other tribes. It was a place of power and trade, ruled by chiefs and blood oaths. There were no white men there, only the whispers of those who had tried and never returned. Mary went alone, carrying a lantern and a load of supplies on her back. The villagers thought she would not last a month. She stayed for nearly thirty years.

In Okoyong, she faced the customs that haunted her letters: human sacrifice after deaths, poison ordeals to prove innocence, wars sparked by insult or debt. But Mary did not fight these practices with guns or orders — she used something subtler. She learned the chiefs’ language, attended their councils, and waited for the moments when compassion outweighed pride. In one of her letters, she wrote: “I have learned that we must stand beside them before we can lead them.”

Still, every act of peace carved new enemies. The colonial authorities grew wary of her independence. She refused to carry a revolver. She built no chapel, but schools. She traded authority for influence, a currency the empire did not understand. In their reports, some officials described her as “too native in sympathy.” Others, more cynical, thought her usefulness had expired.

Yet in Okoyong, she was everything. She nursed the sick, settled disputes, and carried injured men on her shoulders. She was missionary, nurse, judge, and midwife. Her barefooted steps became legend. But behind her calm, her journals reveal exhaustion — fever, loneliness, and a sense of betrayal not from the locals, but from the world that sent her and forgot her.

Betrayal Beneath the Empire’s Flag

By the turn of the century, Mary’s work had drawn attention beyond Calabar. She was honoured in missionary magazines, praised as “the white queen of Okoyong.” Yet she hated that title. It reduced her struggle to a myth — stripped of the sweat, the loss, and the politics that surrounded her. Behind the flattery, the mission board debated her methods. They wanted numbers — baptisms, conversions, reports. Mary sent them none. She sent stories, letters about babies and chiefs and bridges of trust. They called her undisciplined.

It was in those years that the betrayal came — not from the people she served, but from the institutions she represented. The British colonial administration, wary of her influence, began to override her authority. Mission funds were delayed; supplies failed to arrive. Younger missionaries were sent to “supervise” her work. Her health declined, and she found herself defending not her faith, but her dignity.

To the locals, this was incomprehensible — how could her own people doubt her? The chiefs of Okoyong called a council and declared her their own. When British officers visited, they found her sitting beside the elders, equal in voice. That act alone — a white woman sharing power — was rebellion enough. The empire admired her courage but despised her defiance. Letters of criticism trickled back to Scotland. By 1905, her work was being quietly diminished in reports, her name footnoted rather than celebrated.

Still, she continued. Fevered, half-blind, and aging, she refused to return home. “My heart is here,” she wrote, “and my work is not yet done.”

The Final Mission

By 1910, Mary Slessor’s hair had turned completely white, though her eyes still burned with that impossible defiance that once made both chiefs and colonial officers pause. She had long stopped sending reports. Her letters, when they came, were brief—half confessions, half farewells. The fever had eaten away her strength; her hands shook when she wrote. But she continued to travel, walking through flooded forests to settle quarrels, to stop another killing, to deliver a child.

She was no longer the mission’s pride but its puzzle. In Calabar, new missionaries arrived with starched collars and strict timetables. They came to teach discipline, not to share dinner with villagers. They found Mary’s hut unkempt, filled with children and laughter and a disordered kind of peace. She told them the work could not be measured in sermons. They left bewildered, filing quiet reports that questioned her methods. She did not reply. The empire was already receding from her heart.

When she sat beneath the palm trees of Itu, the river glimmering before her like a sheet of molten bronze, she sometimes whispered the names of those she had buried. Babies, mothers, converts, even her fellow missionaries—all swallowed by the land she refused to abandon. The locals said she had become part of the soil, that the earth had claimed her as one of its own.

Her body may have weakened, but her will remained unbroken. The last journey she made was to a distant settlement where a quarrel had erupted between two clans. Against advice, she insisted on going, carried in a hammock through the bush. It rained without pause for two days. When they reached the village, the fight had already ended; she collapsed before the council could greet her. It was as if her purpose had held her upright, and once peace was restored, her body finally allowed itself to fail.

Death in Itu

On January 13, 1915, the woman Calabar called Eka Kpukpru Owo—Mother of All—died quietly in her hut at Use Ikot Oku. The news spread faster than the morning tide. Chiefs from Okoyong, Itu, and Duke Town came down the river in canoes to pay their respects. Some wept openly. They wrapped her in white cloth and placed her Bible on her chest. British officers stood awkwardly among the mourners, unsure how to reconcile this woman who had defied their rule yet represented their mission.

Her funeral was unlike any Calabar had seen. The coffin was carried by local chiefs through the red-earth roads, while hundreds followed in silence. Palm fronds bent low; even the river seemed to hold its breath. She was buried near the mission compound, beneath the shade of a tree whose roots now curl around her grave like an embrace. The inscription on her headstone was simple: “Mary Slessor, Born 1848 – Died 1915. Served God and Humanity.”

But Calabar’s memory was more complex. To the locals, she was no saint carved in marble, but a woman who had lived among them—fierce, flawed, and fearless. To the mission board, she became legend too late. Obituaries in Britain spoke of heroism; none mentioned how the same institutions had doubted her, constrained her, and nearly erased her. History, as always, tidied the story. Calabar, however, kept the messier truth.

The Okoyong elders built a small school in her memory, teaching both English and Efik. They told the children of the woman who had stopped the killing of twins not by conquering their fathers but by listening to their mothers. That, they said, was the real miracle. Her influence outlived empire.

The Walls That Remember

Today, if you walk through the old quarters of Calabar—the ones untouched by glass towers or hotels—you can still feel her echo. The walls are cracked, the air dense with the scent of oil and salt, but the whispers remain. Some houses bear plaques with her name; others are marked only by memory. The children who pass them no longer know the full story, yet when thunder rolls across the estuary, the elders still say, “That is Eka Kpukpru Owo watching.”

But not every memory is kind. Among certain descendants, her legacy stirs debate. Was she a saviour or an intruder? Did she bring enlightenment or erasure? The truth lies somewhere between the extremes. She ended cruelty, yes, but she also stood under a banner of empire, however reluctantly. She sought to humanize Africans to a world that saw them as subjects, yet she did so within the language of her faith—a faith that sometimes dismissed what it did not understand. The betrayal that Calabar whispers about is not only what was done to her but what she unknowingly helped to do: the slow replacement of one system of belief with another.

Still, the land forgives her. The trees around her grave have grown tall. The wind carries the murmur of twin children playing by the river—children who would not have lived without her defiance. Time has made her both accused and absolved, saint and stranger.

The Betrayal

In the end, the greatest betrayal was not by any individual. It was the quiet betrayal of history itself—the way it simplifies courage into legend and scrubs away the loneliness that made that courage possible. The mission board turned her life into a Sunday-school tale, stripped of the nights she spent sweating through fever or the doubts that filled her last journals. The empire that distrusted her later used her story as proof of moral superiority. Even the church that once denied her funds now invokes her name as inspiration.

But Calabar remembers differently. The locals say that in her final months, Mary spoke often of home—not Scotland, but Okoyong. She said she no longer knew where she belonged. The betrayal, perhaps, was realizing that in loving this land so fiercely, she had become too native for her country, yet too foreign for the people who had birthed her faith. She stood between two worlds that never fully claimed her.

And still, she never left. Her death anchored her to the soil of Itu. Her legacy anchored her to the conscience of Calabar. Betrayal, in her case, was not the end of trust but the proof of it—proof that she had loved deeply enough to be wounded by both sides.

Leaving With This: The City That Still Speaks

More than a century later, the story of Mary Slessor lingers in Calabar like the taste of iron in rain. Her grave is now a site of pilgrimage. Schools and streets bear her name. Her portrait hangs in museums beside colonial officers who never understood her. Yet in the quiet corners of the old city, the walls still seem to hum with something else—a low remembrance of the woman who walked barefoot through fever and myth.

When the evening tide rises, the locals say, the water climbs the banks as if to greet her spirit. And when a child cries in the distance, somewhere deep within the mangroves, the sound seems to carry a strange echo—a reminder that once, a woman from far away taught Calabar that some lives are worth saving twice: once from death, and again from forgetting.

Because in Calabar’s old quarters, history is never silent. It listens and it remembers.

Discussion about this post