At dawn, when Lagos is still undecided between light and noise, the factories in Ilupeju hum like a secret only the city understands. Smoke curls from rooftops that once belonged to swamp land, and in the distance, the Eleganza logo catches the sun — a quiet reminder that someone, long ago, bet against doubt and won.

No one remembers the first boy who dreamed of building plastic chairs strong enough to outlive the rains. But those who worked for him remember something else — the silence that followed his decisions. He didn’t talk about wealth; he measured it in work. He didn’t inherit an empire; he assembled it, piece by piece, from the lessons Lagos gave him for free.

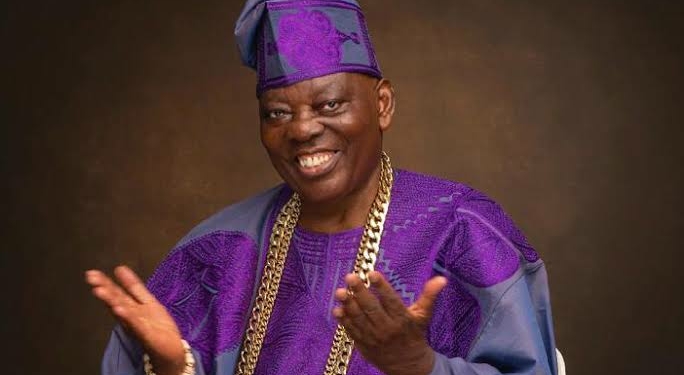

Before the city knew his name, Razaq Akanni Okoya was a boy watching his father stitch old fabrics into new lives. He was born into modest noise — the kind that fills a tailor’s shop on a hot Lagos afternoon — scissors clicking, needles moving, radio murmuring in the background. Somewhere between the sound of thread tightening and the sight of customers returning, he learned the first rule that would later define his empire: nothing is ever truly finished until it sells itself.

He would grow into a man who sold not just products, but belief — belief that Nigeria could manufacture its own tomorrow. But that story, the one that turned a tailor’s son into a tycoon, didn’t start in a boardroom or on a balance sheet. It began in 1940s, in the hands of a boy who thought deeply, spoke rarely, and saw patterns where others only saw poverty.

Born into a Tailor’s Hands (1940s Lagos, The Family Thread)

Razaq Akanni Okoya was born on January 12, 1940, into the household of Tajudeen Okoya, a tailor of discipline and silence, and Alhaja Idiatu Okoya, a woman whose faith was stitched into every corner of their home in Lagos Island. His family was not poor in spirit, but financially, they walked the thin line between sufficiency and lack. The little boy who would later own factories worth millions once fetched water for dyers and carried thread spools for his father’s apprentices.

Lagos in those years was a restless island of migrants, traders, and colonial echoes. Every street corner was a market; every boy was a potential trader. For Razaq, the market wasn’t just an economic space — it was a classroom. He watched how men negotiated, how women multiplied their earnings with patience, and how whispers about new imports dictated daily prices. This early exposure did something irreversible to his imagination: it taught him that commerce was not just about money, but about timing, psychology, and perception.

Okoya’s father valued craft more than profit. He often said that a tailor’s honor was in his stitch, not his sales. But Razaq thought differently. He wanted more than precision; he wanted scale. While his father’s fingers moved gently across fabric, his son’s mind wandered to how many shirts could be made if machines joined those fingers. That conflict — between tradition and ambition — defined the first quiet rebellion in the young Okoya’s life.

By the time he finished Yaba Technical School, Okoya had grown restless with repetition. His father hoped he would inherit the tailoring business, but Razaq wanted to manufacture, not mend. He wanted to create items that could multiply, not singular pieces that faded after one sale. That hunger — raw, daring, and almost rebellious — became the seed that would later birth the Eleganza Empire. But first, he needed to find a way out of his father’s shadow without breaking his father’s heart.

From Apprentice to Merchant (1950s–1960s: The Making of a Hustler)

The late 1950s were the years of trial for every Lagos dreamer. The economy was still tied to foreign dependency, and Nigerian manufacturers were scarce. Razaq Okoya, now in his late teens, took his first steps into independent trade — not as a manufacturer, but as a dealer in imported goods. His first love was fashion accessories — wristwatches, shoes, belts — small things that reflected aspiration. He would buy them in small quantities, sell at a margin, and reinvest quickly. This cycle of movement, from profit to reinvestment, became his oxygen.

His first turning point came when he noticed something others ignored: Lagosians desired beauty but could not always afford imported versions. That gap between want and affordability became his opening. He began to experiment — producing local versions of imported goods with materials sourced within Nigeria. It was a bold step, one that would later define his empire’s identity: local luxury at attainable cost. His first experiments in imitation were not perfect, but they revealed his eye for precision and market timing.

By the early 1960s, he had saved enough to start his first small factory. It was a humble space in Mushin, not the grandeur later associated with Eleganza. There, surrounded by noise, heat, and possibility, Okoya started making jewelry, slippers, and plastic accessories — items that Lagos women loved but couldn’t always import. His workers were young, untrained, but hungry like him. Together, they learned to replicate the fine polish of European goods with local materials and limited machinery.

That little workshop in Mushin became a symbol of resistance — a challenge to the colonial mindset that only imported goods had value. When he registered Eleganza Industries Limited in the mid-1960s, the name sounded aspirational, foreign even. That was deliberate. Okoya wanted Nigerians to associate local products with global elegance. It was his quiet rebellion against dependency — and his calculated way of outsmarting the market’s bias.

The Birth of Eleganza (1970s Lagos, The Empire Emerges)

By the 1970s, the air in Nigeria was filled with oil money and possibility. The civil war had ended, and Lagos was becoming the heartbeat of a newly confident nation. In that moment of national expansion, Okoya’s Eleganza Industries bloomed. His products — plastics, chairs, coolers, and household goods — began to fill Nigerian homes. For the first time, “Made in Nigeria” was not a mark of compromise; it was a symbol of self-sufficiency.

Okoya understood more than economics; he understood psychology. He knew that Nigerians didn’t just want functionality — they wanted aspiration. He studied colors, trends, and packaging, transforming simple household items into desirable products. Eleganza was not merely a company; it was a lifestyle, and Okoya marketed it with silent mastery. Where others advertised, he demonstrated. His factories became showcases; his success became his billboard.

Behind this industrial rise was a meticulous strategist. Okoya reinvested aggressively, refused debt where possible, and expanded horizontally — from plastics to furniture, from jewelry to cosmetics. He built not just a brand but an ecosystem that anticipated consumer needs. His approach to the market was not reactionary; it was predictive. He watched trends before they became visible and positioned Eleganza to dominate those trends once they surfaced.

By the end of the decade, Eleganza had become a household name, and Razaq Okoya, still in his thirties, was already being referred to as “the silent billionaire.” Yet, behind the measured calm of his public image was a restless competitor — one determined to ensure no foreign rival could erase what he had built. The man who began by copying imported goods was now the one being copied.

The Glitter and the Grit (1980s–1990s: Expansion, Rivalry, and Reinvention)

The 1980s came like a storm — wild, oil-rich, and deceptive. Nigeria’s economy was swelling with petroleum profits, but underneath that wealth was a fragile dependency that only the shrewd could read. Razaq Okoya was one of them. While others were blinded by the new naira’s strength, he saw danger in abundance. He doubled production, but never extravagance. He was still that tailor’s son at heart, cautious about waste, obsessed with reinvestment. Eleganza, by then, had outgrown its Mushin beginnings and was fast becoming a national brand.

Factories hummed across Lagos, churning out plastics, chairs, coolers, and household essentials that entered every Nigerian home. At its height, Eleganza employed thousands. Its influence was so large that even imported brands began lowering prices to compete. But Okoya was not distracted by their tactics. He played a deeper game — scale before show, accessibility before applause. In the press, he appeared modest, almost reluctant to speak about wealth. Yet in private, his empire was multiplying, powered by discipline and timing.

By the late 1980s, Eleganza was no longer a business; it was an institution. The young shoemaker’s son had become an industrial monarch, supplying the daily life of a nation. But Okoya knew every empire must evolve or dissolve. And so, as Nigeria stumbled through recessions and structural adjustments in the early 1990s, he began quietly repositioning — trimming excess, modernizing equipment, and preparing for a generational shift that would soon find its face in a woman named Folashade Adeleye.

It was in the late 1990s, long after Eleganza had become a household name, that fate introduced him to Folashade Noimat Adeleye, a vibrant young woman whose intelligence would soon match his discipline. When they married, she became Chief (Dr.) Mrs. Folashade Okoya — not merely his wife, but his collaborator in legacy. Their union marked a new phase: she brought youth, modern vision, and public grace to an empire built on old-school grit. Under her influence, the Eleganza name reemerged with color and contemporary relevance, bridging the past he built and the future she helped design.

The Empire Beyond Eleganza (1990s: Diversification and Domestic Politics)

The 1990s tested every Nigerian industrialist. The oil boom had faded, military regimes controlled foreign exchange, and inflation gnawed at stability. Many manufacturers folded under pressure, but Okoya did what he had always done — he adapted quietly. While others complained about policy, he restructured production. He moved towards greater self-sufficiency, sourcing materials locally where possible, and reducing dependency on imported machinery. This was not just strategy; it was foresight.

He began investing in real estate, building what would later become the Olive Estate and his renowned Eleganza Estate in Ajah, Lagos. These ventures were not vanity projects — they were statements of endurance. Each building reflected a truth Okoya understood early: real wealth must sit on solid ground. The estate became a microcosm of his life — beautiful, self-contained, meticulously planned, and guarded by silence.

By this time, his reputation had shifted from that of a manufacturer to a patriarch. His name carried weight in both industrial and political circles, though he avoided politics. To Okoya, power without productivity was noise. His interviews from this period reveal a man skeptical of government reliance, often reminding younger entrepreneurs that “you don’t wait for policy; you outthink it.” While many of his peers sought government contracts, he built consumer loyalty. That distinction insulated him during years when political transitions crippled others.

The mystery of Razaq Okoya deepened in those years. He became wealthier but less visible. Unlike his contemporaries, who paraded influence through foreign investments, Okoya stayed local. Lagos was his universe — its chaos his currency, its people his partners. Even as globalization swept through Africa, he insisted that Nigeria could still manufacture for itself. It was this stubborn optimism that preserved his empire when imported goods flooded the market again. Where others saw competition, he saw validation — proof that his dream had become the standard others now tried to imitate.

The Mansion and the Mind (2000s: Rebirth in Eleganza Industrial City)

If the early years were about survival, the 2000s were about immortality. By this time, Chief Okoya had begun designing something that would outlast him: Eleganza Industrial City, a vast modern complex in Ibeju-Lekki, Lagos. The project symbolized rebirth — an industrial resurrection for a brand once challenged by global imports. To younger Nigerians, the name “Eleganza” evoked nostalgia; to Okoya, it was unfinished business.

The industrial city became his masterpiece — a sprawling ecosystem of factories producing plastics, chairs, coolers, and everyday goods for a new generation. Folashade Okoya emerged as the public face of this renaissance, while he remained the architect behind the curtain. In interviews, she often described her husband as “a man who never sleeps,” and indeed, even in his seventies, Okoya’s curiosity had not dimmed. He toured factories daily, questioned managers, and remained obsessed with product quality.

What made the Eleganza rebirth profound was not just its economic success, but its symbolism. It showed that Nigerian manufacturing, thought to be dying, could still rise from within — not with foreign capital but with persistence and reinvention. Okoya’s new complex became a pilgrimage site for young industrialists. He opened its gates to students, investors, and government officials, reminding them that vision was not a policy document — it was sweat, steel, and stubborn belief.

The billionaire’s mansion, Oluwanishola Estate, also became legend. Lavish yet disciplined, it reflected his philosophy — wealth should be visible but not vulgar. Its gardens stretched into serenity, its marble floors whispered old money, but behind every chandelier lay the humility of a man who once watched his father measure fabric in inches. The mansion wasn’t built to boast; it was built to remind him where he began.

The Philosophy of Survival (2010s–2020s: Legacy and Reflection)

As Nigeria’s economy swung between promise and crisis in the 2010s and beyond, Okoya became both a teacher and a symbol. Younger entrepreneurs idolized him, not for his luxury, but for his longevity. In a country where many fortunes faded overnight, his endurance became its own mystery. How had one man outsmarted volatility for over six decades? His answer, often repeated, was deceptively simple: “Don’t live for show, live for structure.”

He remained active in industry, guiding the modern phases of Eleganza and mentoring his children into leadership. The family-run structure preserved trust and ensured that Eleganza remained wholly Nigerian. He avoided stock market listings, preferring control to capital — a decision critics questioned but time vindicated. When global markets crashed, Eleganza stayed intact. His foresight, shaped by decades of self-reliance, proved that discipline was the most underrated form of genius.

In interviews, Okoya often reflected on the moral decay of modern business — the obsession with quick profit, the disregard for craftsmanship. He reminded the younger generation that “real wealth is when your workers can feed their families.” That philosophy kept Eleganza human, even as it expanded technologically. He remained unpretentious, still waking early, still inspecting, still grounded.

The man who began as a tailor’s son had become a legend of Lagos — but he wore it lightly. His smile, calm and deliberate, still carried traces of that boy who once watched the market hum at dawn. For him, success was not a spectacle but a discipline. And perhaps that was the true secret: while the market raced to be seen, Okoya mastered the art of staying unseen — yet always ahead.

The Mystery of Mastery (Conclusion)

Today, when the story of Nigerian enterprise is told, Razaq Okoya stands not just as a billionaire, but as a blueprint. His empire was not luck, not inheritance, not government favor — it was built from sweat, silence, and calculation. In a country where noise often replaces impact, he made wealth feel like craftsmanship. He didn’t outtalk competitors; he outlasted them.

The mystery of his success lies not in what he owned, but in how he thought. He saw the market as a living organism — unpredictable yet readable. Where others saw chaos, he saw choreography. Each fluctuation, each scarcity, each boom — all were signals to be interpreted, not feared. And through decades of coups, recessions, and reforms, he navigated them with the precision of a man who never mistook fortune for permanence.

He outmaneuvered the market not by chasing profit, but by predicting need. When others ran after the market, he stood still long enough to understand it. And in that stillness lay the secret Lagos has never forgotten — that mastery is not about speed, but about sight.

Discussion about this post