It began, as Lagos nights often do, with the hum of possibility. From afar, the Eko Hotel and Suites shimmered like a citadel of glass, its façade reflecting the restless breath of Victoria Island. Inside, the chandeliers waited — each crystal droplet poised like a suspended heartbeat. The red carpets had been rolled, the air-conditioned hallways smelled faintly of jasmine and champagne, and a quiet anticipation rippled across the grand ballroom. Lagos’s most powerful men and women were gathering, but there was one arrival that redefined the night.

A sudden hush — then a murmur that traveled like wind over tall grass. Cameras tilted. Broad-shouldered security men adjusted their posture. At the far end of the hall, a small procession emerged: bead-laden chiefs, drummers in matching aso-oke, and at the center, in full regal poise, the Oba of Lagos, Rilwan Akiolu. His entry was neither theatrical nor understated; it was simply inevitable. The lights seemed to bend around him, as if the city itself bowed — that subtle choreography of respect Lagos reserves only for its crowned custodians.

For those who saw it, it was not just a royal arrival; it was a metaphor in motion — the past walking into the present without apology. Around him, men in tuxedos and women in satin evening gowns lowered their phones, momentarily aware that something older than the hotel’s concrete had just entered the room. Tradition, in that instant, was not nostalgia. It was presence.

No one said it aloud, but everyone knew: Eko Hotel was no longer just a venue. It had become a palace for one night — a meeting ground where the soul of Lagos negotiated with its own reflection. Beneath the chandeliers, modernity would pour the wine, and tradition would offer the first toast.

A City Built on Water, Glass, and Memory

Lagos is a state that grows by contradiction. It is both ancient and experimental, traditional and impatient, royal and restless. Its skyline of mirrored towers and its underbelly of history coexist like parallel dreams stitched by traffic and ambition. Lagos does not erase its past; it reassigns it to new coordinates. That is how Eko Hotel came to be not just a hotel, but a symbolic arena for the city’s self-performance.

Built in the 1970s, when Nigeria’s oil boom turned aspiration into architecture, Eko Hotel was imagined as a modern hospitality fortress. Yet, from its earliest days, it attracted a different kind of clientele — monarchs, artists, diplomats, the wealthy, and the weary. Its halls became the neutral ground where kings and CEOs could trade smiles without surrendering authority. To attend an event at Eko Hotel was to be both a witness and a participant in Lagos’s ongoing transformation.

By the time the Lagos @50 Gala was announced in 2017, the hotel had hosted everything — state dinners, oil summits, fashion weeks, music awards, and cultural rebirths. But this night was different. The theme, “Fusion of Heritage and Innovation,” was not a decorative phrase. It was Lagos speaking about its birth, itself in the only language it knows — spectacle.

And so, when the Oba of Lagos accepted the invitation, it was less about attendance and more about symbolism. The city’s first citizen was walking into the house of its newest gods — business, art, and media — to remind them that before skyscrapers, there were crowns.

The Royal Entrance: When the Oba Stepped Into Neon

At around 7:48 p.m., the grand doors opened again. A royal attendant in deep red regalia struck the talking drum — its rhythm commanding silence and attention. The master of ceremonies paused mid-sentence. The ballroom’s LED lights shifted to warm gold. It was as if the entire architecture of Eko Hotel momentarily adjusted to welcome its most consistent guest: tradition.

The Oba’s robe glowed under the amber light, his coral beads cascading down his chest like tributaries of time. His gaze swept across the hall — calculated yet calm, as if measuring how far the city had come since the days when his predecessors ruled by lagoon lanterns rather than fluorescent light. Behind him walked chiefs whose lineage traced back to the Benin dynasty — living reminders that Lagos was never born of modernity alone.

Every photographer in the room raised their camera. And in that instant, the contrast became the composition: royal garments against designer suits, ancient beads against cufflinks. It was not confrontation — it was choreography. This was Lagos showing the world that it could wear its past and future at once, without embarrassment or contradiction.

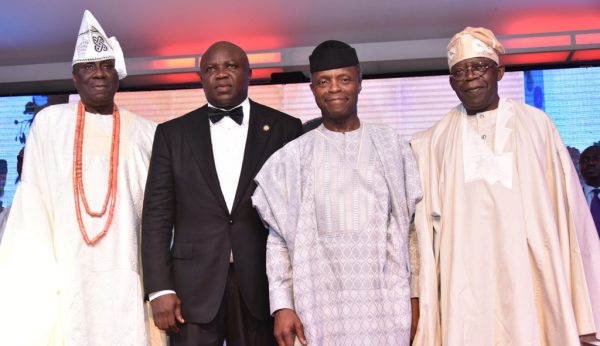

As the procession reached the front table, the Oba exchanged a warm greeting with then-Governor Akinwunmi Ambode, who rose in respect. A few seats away sat Yemi Osibanjo, the vice president then. The Oba nodded. For a moment, Nigeria’s cultural continuum was perfectly aligned: monarchy, governance, and intellect — sharing a table beneath glass chandeliers and ancestral gaze.

Tradition Takes a Seat Beside Innovation

As the dinner began, the emcee introduced a series of performances curated to reflect the city’s journey. A troupe of Yoruba dancers opened with Bata rhythms — powerful, percussive, and ancestral. Then, without pause, a digital projection splashed across the wall — drone footage of Lagos skyscrapers at night, the Third Mainland Bridge lit like a crown of electricity.

The guests applauded, but what few noticed was the symmetry: the Oba’s Ade, the royal crown, shimmered like those lights on the screen. One was ancient gold, the other industrial luminescence — both symbols of power.

When Osibanjo took the microphone later, he spoke about the necessity of remembering origins in the face of global ambition..The Oba nodded, almost imperceptibly, his coral beads shifting with the motion. It was an exchange of philosophies without words.

Governor Ambode, seated between them, leaned toward the Oba and whispered something — a private remark that drew a brief smile. It was that kind of evening: formal yet familial, historic yet human. Around them sat diplomats, oil executives, artists, and royal emissaries — all bound by one shared understanding: Lagos does not erase its past. It repurposes it.

The Sound of Talking Drums and Jazz Notes

It started softly — a talking drum whispered beneath the hum of conversation, like an ancestral voice asking for attention. Then came the brass section, a Lagos jazz band interpreting Fela in symphonic rhythm. The night swelled into something that was neither wholly traditional nor entirely modern, but uniquely Lagosian — a music that moved like traffic and memory.

The drummers, dressed in cream agbada with red caps, didn’t play for entertainment alone. They were communicating. Every beat carried a coded greeting, a salute to the royal presence. “Kabiyesi o!” one rhythm called. The trumpets answered with syncopated defiance. It was dialogue through sound — the kind that only Lagos can stage without irony.

The Oba, still composed in his seat, tapped his fingers lightly on the table. It was a small gesture, but those who noticed it smiled knowingly. For a monarch whose reign bridges colonial residue and digital redefinition, this fusion wasn’t strange — it was prophecy. The night’s music proved that even tradition can improvise.

Later, when the band paused for applause, a younger musician — an Afrobeats producer in designer sneakers — leaned toward a drummer and murmured, “You people started what we’re now streaming.” The drummer laughed. That’s Lagos: a place where the past doesn’t die; it remixes itself.

Royalty and the Business of Prestige

Royalty in Lagos no longer reigns over territory alone — it reigns over perception. To see the Oba of Lagos at Eko Hotel is to witness an institution adapting to the rules of visibility. In the old days, kings communicated through emissaries; now they are photographed beside CEOs and artists, becoming part of the city’s social currency. Prestige, like gold, has become both ancient and marketable.

At the Lagos @50 Gala, this was evident in every corner. The hotel’s foyer was lined with luxury brand logos: beverage sponsors, automobile displays, real estate developers promoting “heritage-inspired living.” Yet, the Oba’s presence turned all of them into background noise. The crown itself remained the most authentic brand in the room — older than any company, yet still relevant.

Across the hall, media executives whispered about live coverage angles. The organizers had placed the Oba’s table strategically — visible from every camera. It wasn’t vanity; it was respect codified in production design. The message was clear: Lagos honors its throne, even when celebrating its skyscrapers.

That night, business leaders like Obi Cubana, Herbert Wigwe, and Folorunsho Alakija mingled in quiet circles, each aware that heritage legitimizes ambition. The Oba’s nod — a small tilt of the head — was a blessing beyond finance. It was the cultural handshake every billionaire desires in a city where money buys everything except lineage.

Eko Hotel: The New Palace of Conversations

In another century, this gathering would have taken place in a courtyard lit by palm oil lamps. But Eko Hotel had long become Lagos’s “neutral palace” — the place where hierarchy became hospitality. Since the early 1980s, presidents and traditional rulers had used its banquet halls as informal political ground. Here, the Oba of Lagos could meet the President of Nigeria, the Sultan of Sokoto, or the Archbishop of Lagos without breaching any territorial etiquette.

The hotel’s architecture itself seemed to invite duality — European modernism on the outside, Yoruba sensibility on the inside. Its grand ballroom, with ceiling mirrors and ambient percussion, had hosted not only coronation dinners but also Afrobeats award nights. It was the one venue where Davido and an Emir might both appear on the same program — one closing the show with a microphone, the other with a prayer.

The night of the Lagos @50 Gala, the hotel stood as a metaphor for the city’s evolution. Waiters in black bow ties moved between tables carrying plates of peppered snails and grilled salmon. The drummers alternated with a jazz quartet. Every sound in that room — from the rustle of silk wrappers to the hum of conversation — told a single story: Lagos, the negotiator, never chooses between tradition and modernity. It hosts both, and lets them talk.

For Oba Akiolu, the symbolism was not lost. He had witnessed Lagos change from colonial port to financial capital, from trade hub to tech incubator. Yet here he was, sitting comfortably in a setting that once would have been considered foreign, now redefined by local rhythm.

The Meaning of Presence: What the Crown Represents in a Modern City

In a democracy that prides itself on modern governance, the relevance of a monarch might seem symbolic. Yet in Lagos, symbols still move mountains. The Oba’s appearance at events like this is never just ceremonial — it is social choreography. He is not merely the custodian of tradition; he is its interpreter in an age that trades in perception.

The Lagos @50 Gala required more than decoration — it needed legitimacy. The Oba’s presence provided that. His coral beads reminded the audience that before stock markets and smart cities, there were markets run by kinship and honor. His Ade — heavy and radiant — spoke of history’s endurance in a city obsessed with speed.

For many in the room, especially younger attendees, seeing the Oba in such modern space was revelatory. He was not frozen in time; he was adapting — the living proof that culture can walk beside commerce without losing its dignity. His poise, his silence, his subtle gestures communicated what speeches could not: that Lagos is not a place that forgets its fathers while chasing the future.

Outside, the lagoon lapped softly against the hotel’s edge. From afar, the Eko Tower lights blinked like urban stars. But inside, the quiet gravity of a crown reminded everyone that not all lights are electric. Some come from memory.

Faces Around the Table: Tinubu, Ambode, the Diplomats, and the Drummers

It was a table that could have been painted. Wole Soyinka, with his white halo of hair, leaned slightly forward — listening, analyzing, as though the night itself were a metaphor. Beside him, Governor Ambode exchanged words with foreign diplomats from France, the United States, and Ghana. At the far end, drummers rested their instruments, their hands still vibrating from rhythm.

Every face told a story of Lagos: Tinubu, the political head; Ambode, the administrator; the Oba, the custodian; the drummers, the memory. And around them, the elite — bankers, tech founders, musicians — each representing a fragment of the modern city’s pulse.

When the toast was raised, the Oba lifted his glass — not high, but with deliberate calm. Cameras clicked. For those who would later scroll through the photographs, it was another high-society image. But for those present, it was a covenant. A visual reminder that the city’s foundation — respect, rhythm, resilience — was still intact beneath the steel and neon.

Even the waiters, moving between tables with practiced grace, felt the weight of the evening. “Kabiyesi is here o,” one whispered to another, half in awe, half in pride. It wasn’t reverence for monarchy alone — it was acknowledgment that Lagos’s story still had authors who remember its proverbs.

Echoes From Other Nights: Oriental, Wheatbaker, Radisson

This wasn’t the first time tradition had walked through revolving hotel doors in Lagos. At the Oriental Hotel Art Banquet of 2018, Yoruba royals stood beside modern art collectors; ancient motifs were auctioned in digital catalogs. At The Wheatbaker, the Ooni of Ife shared cocktails with designers who embroidered adire into haute couture — a vision of what Yoruba nobility could look like in Milan or Paris.

In 2021, at the Federal Palace Hotel, the Obas of Ikate and Iruland sat opposite oil magnates and foreign investors — an unlikely dinner table where ancestral authority negotiated with capitalism. And at Radisson Blu, in 2022, Oba Saheed Elegushi spoke beside filmmakers and entertainers about relevance in the digital age.

Each event, like chapters in Lagos’s modern myth, redefined what it meant to be royal in the twenty-first century. The Oba of Lagos’s presence at Eko Hotel was not an isolated spectacle; it was part of a larger Lagos habit — tradition reinventing itself within marble lobbies.

These hotels, more than mere buildings, had become modern palaces — spaces where cultural hierarchies are not destroyed but translated. To walk into one on a night like this is to watch Nigeria’s identity negotiating its next version of itself.

Closing Reflections – When the Lights Dimmed, and Lagos Looked at Its Reflection

By midnight, the hall had begun to empty. The scent of ofada rice and French wine still lingered in the air. The chandeliers dimmed one by one, their glow softening into a memory. Outside, the Oba’s convoy waited, headlights cutting through the night mist that rose from the lagoon.

As he rose, applause followed — spontaneous, uncoordinated, almost grateful. People weren’t clapping for monarchy alone; they were clapping for Lagos itself — for a city that could bring its history to dinner and make it feel at home. The Oba nodded once, and the drummers struck a final rhythm — a closing benediction that echoed off marble and glass.

When the last car drove away, Eko Hotel fell silent again. But the night had left something behind — an aftertaste of grace, an invisible handshake between eras. Somewhere between those chandeliers and coral beads, Lagos had seen itself clearly: both crown and skyline, both lagoon and neon.

And that is what makes nights like this matter — not for spectacle, but for memory. Because every time the Oba of Lagos steps into Eko Hotel, the city is reminded that modernity without roots is merely decoration. In that shared space — between drums and jazz, coral and chrome — Lagos rehearsed its own truth once again: that tradition and modernity are not rivals here. They are tablemates in a city that feeds on both.

Discussion about this post