The night breeze over Redemption Camp carries a strange kind of silence. It is not the silence of emptiness but of expectancy — the hush that precedes a shift no one can yet name. Somewhere beyond the echo of the altar lights and the sprawling sea of plastic chairs, a question hangs in the air like unspoken prophecy: what happens after the fathers are gone? Across Ogun, Ota, and Gbagada, three pulpits glow under aging hands that once shaped the spiritual architecture of Nigeria. They are men who became movements — Adeboye, Oyedepo, Kumuyi — each commanding not just churches, but civilizations of faith.

For decades, they have been the center of gravity in Nigerian Pentecostalism, their voices setting the rhythm for a nation’s soul. Their congregations span continents, their sermons interpreted into dozens of tongues, their annual gatherings outnumbering cities. But under the hymns and hallelujahs, beneath the protocols of reverence and continuity, lies a puzzle no one wants to solve too quickly — the question of succession. Not merely who will lead next, but whether the fire can ever burn the same in another vessel.

Succession in Nigeria’s Pentecostal landscape is not just organizational; it is deeply spiritual, almost mystical. These churches were not born as corporations; they emerged from revival fires, fasting mountains, and nights of visions. To name a successor, therefore, is not just to appoint — it is to anoint.

Yet, as age and mortality knock on the doors of their founders, the question no longer hides behind faith. It walks the corridors of their auditoriums, whispering in board meetings and echoing through congregational prayers.

The puzzle is not that these men will die someday — even they acknowledge that. The puzzle is that no one is sure how their empires will survive their absence. The Redeemed Christian Church of God (RCCG), Living Faith Church (Winners Chapel), and Deeper Life Bible Church were built on personal revelation, divine authority, and charismatic energy.

Can revelation be transferred by committee? Can charisma be inherited by policy? In this silence, Nigeria’s largest faith communities wait for the inevitable, uncertain if heaven’s order aligns with earthly succession.

The Adeboye Enigma: The Mantle Beyond Redemption

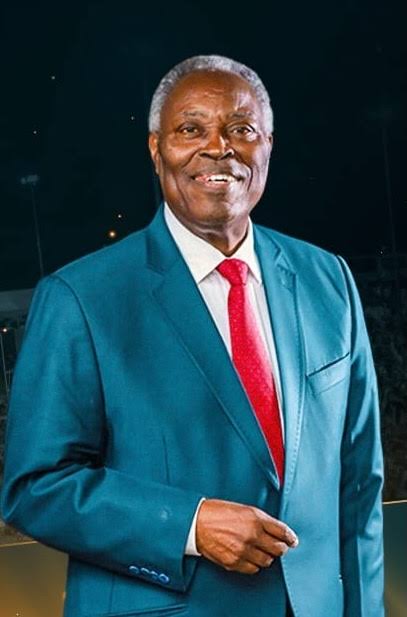

Pastor Enoch Adejare Adeboye, the soft-spoken mathematician who became “Daddy G.O.,” has led RCCG since 1981. Under his watch, the church transformed from a local revivalist group into a global Pentecostal powerhouse. He built not just branches but nations within nations — Redemption Camp itself has become a city of faith, with banks, schools, and a population large enough to rival state capitals. But with greatness comes a paradox: Adeboye’s humility is both the glue and the lock. Everything revolves around him, and yet he insists it is not about him.

At 83, the General Overseer still travels, preaches, and presides over marathon conventions that stretch into dawn. His calm delivery belies an inner discipline that has shaped the culture of the church. But within RCCG, discussions about succession are whispered, not spoken. In 2017, when he briefly appointed Pastor Joshua Obayemi as the national overseer, confusion rippled through the ranks until Adeboye clarified he remained the global leader. The episode exposed what the church had long known but rarely admitted — no one else can fill his shoes, at least not yet.

Adeboye’s model of governance blends divine authority with administrative decentralization. Each province has its pastor, each region its overseer, yet every sermon, every project, every doctrine bends toward his spiritual gravity. His son, Leke Adeboye, already plays a visible role as personal assistant and youth influencer. Yet even he has publicly denied interest in leadership succession, echoing his father’s caution against dynastic transfer. In RCCG’s ethos, leadership is not inherited — it is revealed. But revelation, by nature, resists scheduling.

Still, the shadow grows longer. Many within RCCG quietly study the transition model of the Catholic Church, wondering if a “college of elders” or council of provincial heads could sustain continuity. Others believe only divine intervention will reveal the next mantle-bearer. For now, Adeboye’s continued vitality feels like grace prolonged — a stay of time before the most delicate question in Nigerian Christianity must be answered.

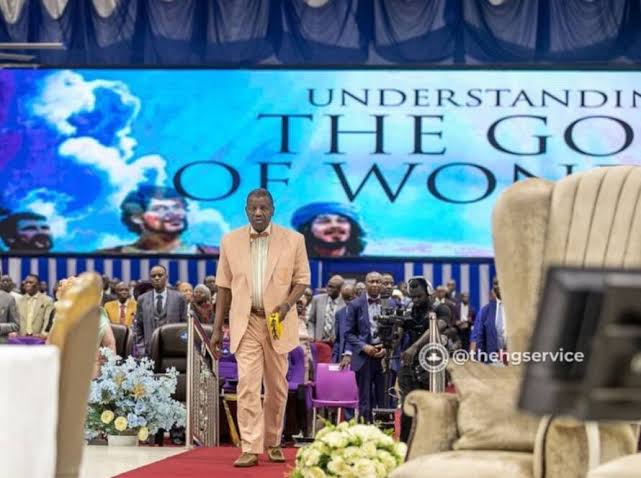

Oyedepo’s Covenant of Continuity

If Adeboye embodies humility, Bishop David Oyedepo personifies authority. Where RCCG’s hierarchy is diffuse, Winners Chapel’s structure is corporate precision guided by prophetic centrality. Oyedepo, the founder and presiding bishop, built an empire of faith rooted in what he calls the liberation mandate — a divine assignment that has fused prosperity theology with audacious infrastructure. From Faith Tabernacle’s 50,000-seat sanctuary to Covenant University’s intellectual fortress, his model of church leadership is not democratic but covenantal.

At 71, Oyedepo remains vigorously present, still commanding energy on the altar that could rival his own younger pastors. Yet, within the inner corridors of Canaanland, the question of who carries the “liberation mantle” has begun to mature from curiosity to concern. Unlike Adeboye, Oyedepo’s succession appears more structured — not only because of his family involvement but because the Living Faith Church operates with a clear executive framework. His two sons, David Oyedepo Jr. and Isaac Oyedepo, have both served in senior pastoral roles, with David Jr. leading the Abuja church and Isaac formerly heading the Maryland branch in the United States.

In 2023, Isaac Oyedepo’s temporary exit from the church stirred speculation about internal differences and the broader question of succession. Though he later reaffirmed loyalty, the episode revealed the fragile balance between spiritual calling and family expectation. Oyedepo has often warned that “the mandate is not a family property,” yet his sons’ prominence makes the church’s next chapter almost impossible to separate from the Oyedepo name.

Still, if any of Nigeria’s megachurches is structurally prepared for transition, it is Winners Chapel. The church’s hierarchical order, institutional investments, and doctrinal rigidity ensure it could survive administrative succession. What cannot be easily replicated, however, is Oyedepo’s prophetic charisma — the conviction, voice, and defiance that built an empire where others saw only tents. When he finally steps aside, continuity may be ensured, but conviction is harder to transfer.

Kumuyi’s Quiet Blueprint

Pastor William Folorunso Kumuyi is the most reclusive of the three. He rarely courts publicity, his ascetic personality standing in contrast to Pentecostal flamboyance. Yet Deeper Life Bible Church, born in 1973 from a university fellowship, became one of Africa’s largest holiness movements. His theology is austere, his discipline legendary, his sermons marked by precision and doctrinal purity. In an era of “breakthrough” preaching, Kumuyi’s message remains simple: repentance, holiness, and heaven.

At 84, Kumuyi still preaches with mathematical order and pastoral restraint. But succession within Deeper Life is an even greater enigma than RCCG’s. The church has no visible deputy structure, no public grooming of successors, no family front-runner. Kumuyi’s wife, Esther Kumuyi, plays a supportive role, but not a ministerial one. Leadership is distributed through zonal and regional overseers, yet the power of doctrine — and the authority of purity — begins and ends with him.

When members began openly asking for a named successor, Kumuyi did not answer with a bland administrative statement; he rebuked the demand. In public and in private addresses he has sharply warned against impatience and the rush to catalogue God’s plans, arguing that pushing for a named heir can breed factionalism and distract the church from holiness. His rebukes were not merely defensive: they were theological—he framed the insistence on a successor as a misplaced attempt to domesticate divine timing, something that, he warned, risks turning spiritual stewardship into human ambition.

Unlike RCCG and Winners Chapel, Deeper Life’s growth has plateaued in recent years, its once-dominant moral ethos challenged by younger Pentecostal expressions. Some within the church quietly advocate for generational renewal, fearing the purity movement may fade with its founder. Kumuyi’s public posture — rebuking calls for succession while emphasizing doctrinal continuity — suggests he prefers a transition shaped by spiritual formation rather than public appointment. His approach may be enigmatic, but it is consistent: ensure the doctrine survives, and let God reveal the steward in His time.

The Hidden Battles of Succession

Behind the polished pulpits and televised services, succession is not a holy abstraction. It is a human struggle — one that touches faith, ego, and survival. Within these megachurches lie thousands of pastors, assistant ministers, and administrative boards, all functioning under unwritten laws of reverence. To even hint at succession while the founder lives is often interpreted as rebellion. The culture of Pentecostal hierarchy makes open dialogue almost taboo.

But the inevitability of mortality is rewriting that silence. Across African Pentecostal history, the fall of a founder often births fragmentation. The Apostolic Church, the Celestial Church of Christ, and even some Aladura movements fractured after their patriarchs departed. It is this ghost of history that haunts RCCG, Winners, and Deeper Life. Each knows that without clear transition, unity becomes memory. Yet each fears that open discussion could ignite premature ambition.

The challenge is also generational. The founding fathers built their ministries in an era of scarcity, revival, and moral fervor; their successors must lead in an age of digital distraction, moral relativism, and media capitalism. The new church must be fluent in both holiness and hashtags, in both doctrine and digital. That requires a kind of leader Nigeria’s Pentecostal tradition is yet to produce at scale — young enough to innovate, yet mature enough to command reverence.

As these leaders age, the inner contest is no longer who will succeed, but whether the next generation can sustain the sacred without diluting it. In that balance lies the battle no one preaches about — the war between continuity and change, between the spirit that birthed revival and the structure that now protects it.

Faith, Family, and the Burden of Transfer

Family complicates the holy equation. In African spirituality, legacy often passes through blood; in Pentecostal theology, it passes through calling. Reconciling both is the burden of modern megachurches. Adeboye, Oyedepo, and Kumuyi have all raised children in ministry-adjacent spaces, yet each has resisted formal dynastic transition. Still, their influence on their families is undeniable — the sons and daughters raised on crusade grounds now carry echoes of their fathers’ vision.

For Adeboye, family is testimony. His children have grown within the spiritual ecosystem he built, but his caution against nepotism remains firm. For Oyedepo, family is both foundation and frontier — his wife Faith Oyedepo is co-founder, and his sons are public figures in ministry. For Kumuyi, family is private, almost sacredly withdrawn. His approach to leadership avoids even the suggestion of bloodline succession, maintaining purity of purpose above lineage.

Yet in every megachurch history, the human heart complicates theology. Followers find comfort in continuity — seeing familiar names sustain faith structures. Dynasties may not be doctrinal, but they are emotional. The line between divine choice and human inheritance often blurs under the lights of loyalty. And when founders live long enough to witness their children rise, the line blurs further still.

Succession, therefore, is not just a question of leadership; it is a question of inheritance. Not inheritance of wealth or property, but of spirit — the unseen DNA that turns a congregation into a community. Whether that inheritance can outlive its founders remains the quiet tension of every altar they built.

The Prophecy of Longevity

Each of these men has outlived their peers. Longevity itself has become part of their legend, almost a prophecy fulfilled. Adeboye’s measured health, Oyedepo’s tireless schedule, Kumuyi’s enduring discipline — all seem to defy time. Their followers interpret this as grace; their critics, as refusal to relinquish control. But both perspectives miss a deeper truth: longevity in leadership has preserved stability in Nigeria’s Christian architecture.

Still, longevity is not immortality. The average age of Nigeria’s top Pentecostal leaders now exceeds 70. Behind them, a younger crop of pastors — Nathaniel Bassey, Jerry Eze, Daniel Olawande, and others — represent a different spiritual generation: less hierarchical, more digital, yet still shaped by their fathers’ legacies. When the old guard eventually bows out, the question will not only be who succeeds them but whether the Nigerian church itself can evolve without losing its identity.

Prophetically, each founder has hinted that God will choose their successor. Adeboye calls it “heaven’s prerogative.” Oyedepo frames it as “mantle continuity.” Kumuyi calls it “the Lord’s will.” Yet, divine timing rarely announces itself in constitution. At some point, spiritual revelation must meet administrative structure — a collision point that could define the next fifty years of Nigerian Christianity.

Until then, the prophecy of longevity remains a blessing and a delay. Their continued presence steadies millions, yet postpones the inevitable reckoning of transition. The longer they live, the more their ministries depend on their singular presence — and the greater the shock when that presence is gone.

The Future Church: Between Structure and Spirit

The next generation of Nigerian Christianity stands at a crossroads between structure and spirit. RCCG’s administrative vastness, Winners Chapel’s corporate discipline, and Deeper Life’s moral orthodoxy each reflect different faces of Pentecostal evolution. But the future may not belong to any single model. It may belong to those who can merge spirituality with strategy, revelation with reform.

The lessons from Africa’s religious past are sobering. Movements that fail to institutionalize their charisma often collapse after their founders. Yet, churches that institutionalize too rigidly risk losing revival’s fire. Adeboye’s RCCG is evolving into a global denomination; Oyedepo’s Winners Chapel already operates like a multinational; Kumuyi’s Deeper Life remains a doctrinal monolith. Each model holds both promise and peril.

The key may lie in mentorship — not appointment, but formation. The next Adeboye, Oyedepo, or Kumuyi may not emerge from direct succession but from the countless pastors shaped under their ministries. In those unseen disciples, the spirit of the fathers may find continuity. But for that to happen, the fathers must bless the sons — publicly, intentionally, and without fear.

Nigeria’s Pentecostal future will not just be decided by sermons, but by systems; not by prophecies alone, but by preparation. The true legacy of these fathers will not be the cathedrals they built, but the stability they left behind when their microphones finally fell silent.

Leaving With This– When the Fathers Fall Silent

Someday, the altars will dim. The familiar voices will fade into recordings, the prayers that once shaped nations will echo only in archives. The crowds will still gather — not out of nostalgia, but out of need. For faith, like life, always seeks a face to follow. When that day comes, Nigeria’s greatest test of faith may not be belief, but continuity.

The fathers built a world where God was near, where purpose was measurable, and destiny could be charted through obedience. They turned barren lands into sanctuaries and gave a restless generation something sacred to pursue. Their absence will not end that pursuit; it will only redefine it. For every mantle that falls, another hand must rise to catch it.

And perhaps that is the unseen answer to the succession puzzle — that it was never about replacement, but renewal. The true heir to their legacy may not be one man, but a generation. The voices they raised, the lives they transformed, the faith they sustained — these are their living successors. The puzzle, then, is not who comes next, but how long their echo will last.

Discussion about this post