In the beginning, every performer needed two faces: one for the world, another for survival. Somewhere between the spotlight and the street corner, between church choirs and smoky studios, Nigerians learned that to become known, you must first become someone else.

The mystery of Nigerian stage names isn’t only about artistry — it’s about camouflage. In a nation where names carry ancestry, spirituality, and expectation, adopting a new one can be both rebellion and rebirth. It’s an act of reinvention, an erasure of class or tribe, and sometimes, a small resistance against what destiny already wrote in one’s baptismal certificate.

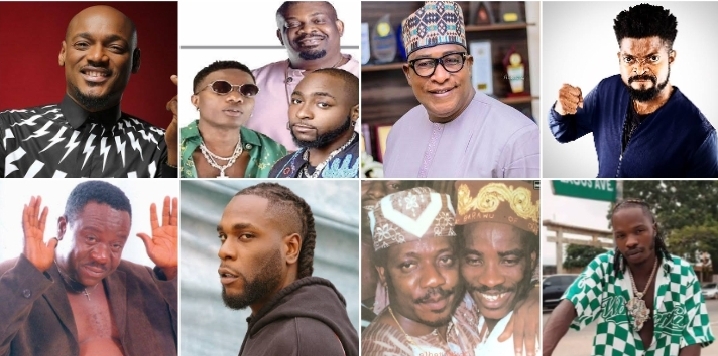

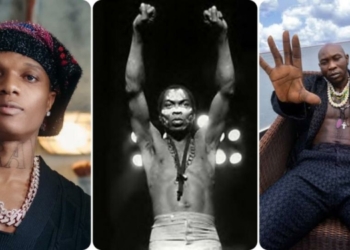

Every generation of Nigerian entertainment — from the highlife crooners of Enugu to the Fuji kings of Mushin and the digital rappers of Lekki — has left behind a trail of renamed selves. But behind the glamour of Davido and the enigma of Burna Boy, lies a story older than pop: a culture of self-recreation that mirrors the nation’s restless search for identity.

In the Beginning, They Renamed Themselves to Be Heard

Long before Instagram handles turned aliases into algorithms, Nigerian performers were already experimenting with the power of naming. In the 1940s and ’50s, when Lagos was still a patchwork of colonial and local rhythms, Highlife bands became the earliest laboratories of stage identity.

The likes of Bobby Benson, born Bernard Olabinjo Benson, knew that “Bobby” would echo louder on Western radio waves. The same logic guided Victor Olaiya and Cardinal Rex Lawson — a calculated blend of local rhythm and colonial polish. These weren’t mere monikers; they were bridges between self-expression and global aspiration.

When Benson renamed himself, he wasn’t just shortening a Yoruba name; he was rearranging destiny for broadcast clarity. In that small gesture, he captured the paradox of Nigerian entertainment — the need to belong to the world without dissolving into it.

But as Nigeria gained independence, naming took a new turn. Colonial imitation gave way to cultural assertion. Artists began using names that defied English neatness — ones that carried thunder, laughter, or defiance.

The Theatre of Masks: Yoruba Travelling Troupes and the Birth of Persona

If Highlife musicians borrowed Western rhythms, Yoruba theatre reinvented naming as spiritual theatre.

From the 1950s to the 1980s, the itinerant theatre movement — led by figures like Hubert Ogunde, Duro Ladipo, Moses Olaiya (Baba Sala), and Oyin Adejobi — turned performance into both ministry and masquerade.

Here, the stage name was more than brand; it was a totem. Baba Sala, for instance, was not simply a comic alias — it was an alternate life form: mischievous, childlike, yet wise. Audiences often forgot that Moses Olaiya existed outside his character. The name consumed the man, the man became myth, and the myth fed a national appetite for laughter amid hardship.

In these troupes, every actor carried a dual identity — a birth name for home, and a stage name for the road. The shift symbolized freedom from the village gaze, from the moral rigidity of community life.

To rename oneself was to rewrite fate. Ajimajasan, Iya Awero, Adebayo Salami (Oga Bello) — each name carried coded humor, class positioning, and subtle reverence. Naming became performance art itself — a balancing act between ego and humility, audience and ancestry.

The Sound of the Streets: Fuji’s Hidden Messages

By the 1970s, in the narrow alleys of Mushin and Ibadan, another naming tradition rose — raw, improvised, and fiercely competitive: Fuji.

Fuji music was born from Islamic praise chants and Yoruba oral poetry, and with it came a new lexicon of stage identities — often flamboyant, self-proclaiming, and spiritual.

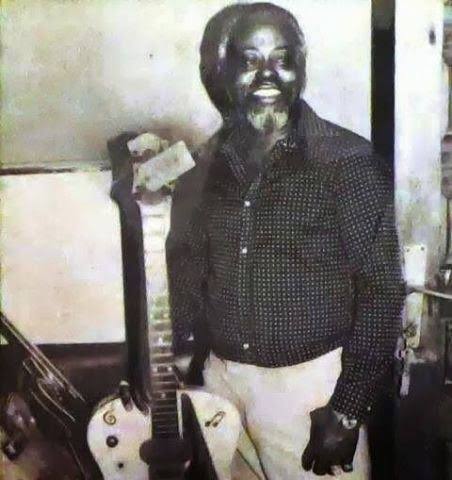

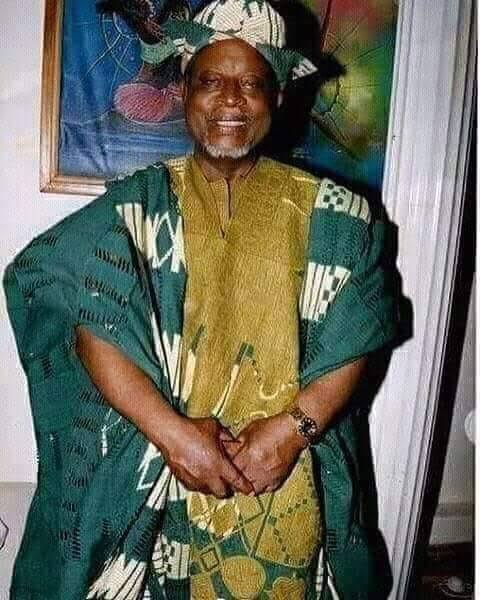

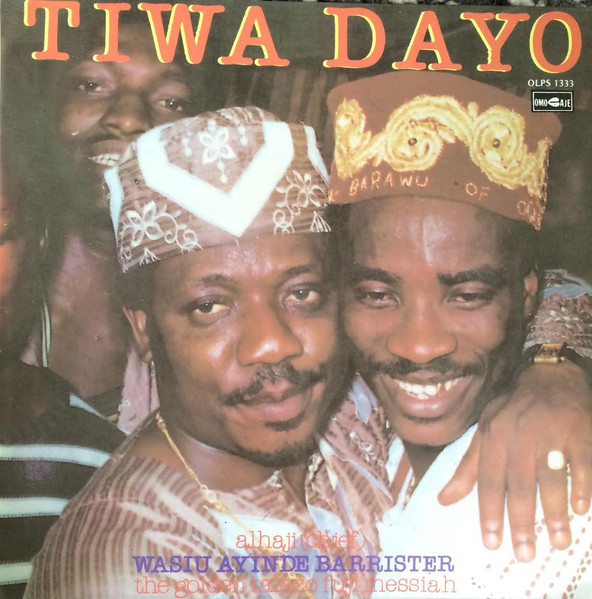

Alhaji Sikiru Ayinde Barrister created an entire mythos around his title — blending military imagery (“Barrister”) with piety (“Alhaji”). His rival, K1 De Ultimate (formerly Kwam 1, King Wasiu Ayinde), later reinvented himself with each era, using renaming as a tool for dominance.

To adopt a name in Fuji was to stake a claim in a social hierarchy. The name could praise, provoke, or intimidate. It could carry coded warnings to rivals or political subtexts to fans.

Stage naming here functioned as survival — an armor in a lyrical battlefield. In this universe, losing one’s name was tantamount to defeat.

The Nollywood Revolution: When Fame Needed Familiar Faces

By the early 1990s, Nollywood emerged — not from studios, but from markets, backyards, and prayer meetings.

Video producers needed actors who could sell VCDs by name alone. It was the era of home video identity — when the right alias could carry a film from Alaba to Onitsha overnight.

Some names stuck by accident. Mr. Ibu wasn’t meant to outgrow John Okafor — but the comic character became his true public identity. Similarly, Osuofia swallowed Nkem Owoh, Saint Obi became both role and reputation, and Patience Ozokwor’s “Mama G” transformed from a screen name into a social archetype.

The mystery here wasn’t just branding. These names reflected Nigeria’s cultural fragmentation — how the people preferred recognizable myths over complex individuals. In an economy of piracy and poverty, the name itself became a form of copyright — a public mark no one could steal.

By the late 2000s, stage names were no longer camouflage — they were commercial weapons. They could build or break a career.

The Music Industry and the Reinvention Economy

When the internet disrupted distribution, stage names evolved again — this time as searchable identities. Artists were now competing not on record shelves but on algorithms. The mystery of Nigerian stage names entered its digital phase.

2Baba, Davido, Wizkid, Burna Boy, Tiwa Savage — each name was a calculated equilibrium between simplicity and immortality. These weren’t random nicknames; they were data-conscious, trademarkable emblems.

But they still carried shadows of earlier traditions. Burna Boy reactivated the Barrister-style bravado. Olamide kept his real name as rebellion against anonymity. Tems turned abbreviation into allure. Asake, by using his mother’s name, turned personal heritage into spiritual branding.

Stage names now moved between worlds — part Yoruba praise poetry, part Silicon Valley optimization. The artist was both oracle and entrepreneur, both son of the soil and child of Spotify.

Hidden Histories and the Weight of Meaning

In Nigeria, every name carries cosmology. To change one is to tamper with fate.

The hidden story behind many stage names is often spiritual negotiation.

A Pentecostal background might reject ancestral connotations, leading to a “neutral” alias; a Muslim performer might hide religious roots to appeal to secular markets; others use names to reclaim identity from colonial or tribal bias.

There’s also the pain of erasure: female artists often rebrand to escape patriarchal scrutiny. Think of how early Nollywood actresses used “Liz,” “Rita,” or “Regina” — names with universal softness — in a society where traditional femininity was policed.

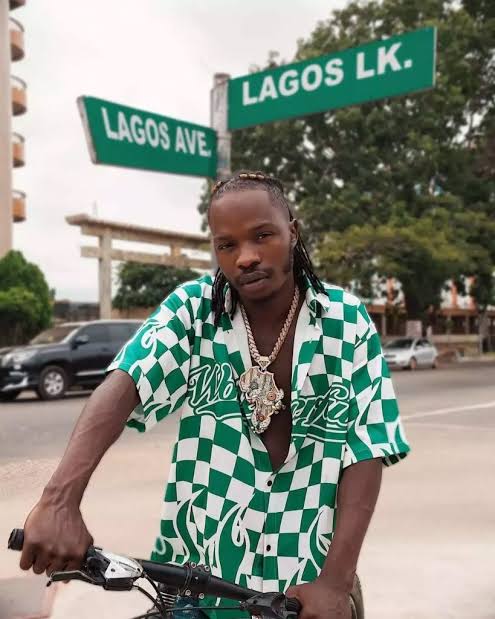

And some names carry irony. Portable, a man anything but restrained. Naira Marley, whose moniker mocks the economic chaos around him. Blackface, whose controversial name still stirs racial undertones beyond its local context.

Behind the glamor lies something darker: the constant negotiation between personhood and performance. Stage names hide family disputes, religious transformation, trauma, or reinvention after failure. In Nigerian entertainment, identity is never static — it’s currency.

The Politics of Naming and National Identity

To trace Nigerian stage names is to trace Nigeria itself — a nation forever renaming, rebranding, restarting.

Colonialism renamed cities and institutions. Independence renamed ideals. Artists merely mirrored that national schizophrenia — the restless need to become “new” again.

When entertainers call themselves King, Prince, Queen Mother, Area Fada, or Ezege, they aren’t just claiming authority — they’re performing Nigeria’s obsession with titles, a reflection of a society where identity equals validation.

Even within politics, entertainers-turned-public figures like 9ice or Banky W retained their stage names, because their invented selves had become more trusted than their real ones.

Stage names blur the line between authenticity and mythology — but in Nigeria, that’s precisely how survival works. To exist, one must brand oneself before being branded by circumstance.

In the Age of Virality, the Name Speaks Before the Song

Today, stage names circulate faster than the music itself. TikTok hashtags make identities before artistry. YouTube thumbnails demand one-word recognizability. The artist is now a visual brand before a sonic one.

In this ecosystem, names must be short, searchable, memeable — but still drenched in mystery. That’s why Rema, Fireboy DML, Bloody Civilian, Ayra Starr, and Odumodublvck each sound like coded phrases, not just names. They’re designed to evoke curiosity — to make the listener feel there’s more behind the surface.

Yet even now, the old spirit lingers. Odumodublvck, for instance, carries a modernized ancestral energy — a performer adopting the tone of a griot. Ayra Starr’s celestial name draws from both biblical and Afrofuturist imagery. Rema’s moniker feels minimalist but mystical.

Every generation of Nigerian artists returns, in new language, to the same ancient urge: to name oneself before the world names you.

The Double Life of Identity

Some entertainers maintain the divide between the stage and the self with surgical precision. The name becomes a wall — a private barrier that guards mental health, family, and faith.

But others lose themselves in the persona. For Mr. Ibu, the fictional buffoon eventually became the man; for some musicians, the adopted identity becomes too famous to shed. It is both liberation and prison.

This is the paradox of Nigerian fame — to achieve success, one must create an alternate self that often overshadows the original. And yet, without that creation, the artist might never have been seen at all.

Legacy and the Mystery That Remains

Perhaps that is why the story of Nigerian stage names feels both intimate and epic. Each alias is a story of transformation — a whisper of reinvention in a country that demands resilience.

The names hide pain, faith, and sometimes, the simple hunger to belong.

They are memoirs disguised as monikers.

From Bobby Benson’s saxophone to Burna Boy’s stadium roar, every generation of Nigerian artists has used naming as both mask and mirror. The mystery of Nigerian stage names is ultimately the mystery of the nation itself — a country perpetually performing, forever renaming, endlessly reborn.

Closing Reflection — When the Spotlight Goes Off

When the lights dim and applause fades, the performer often reverts to their real name — the one the world rarely calls.

In that silence lies truth: fame may decorate the mask, but it’s the unseen name that carries the soul.

Nigeria’s stage names are not hiding deception; they’re hiding survival — and sometimes, salvation. Because in a land where becoming yourself can be dangerous, the bravest act may simply be to become someone else.

Discussion about this post