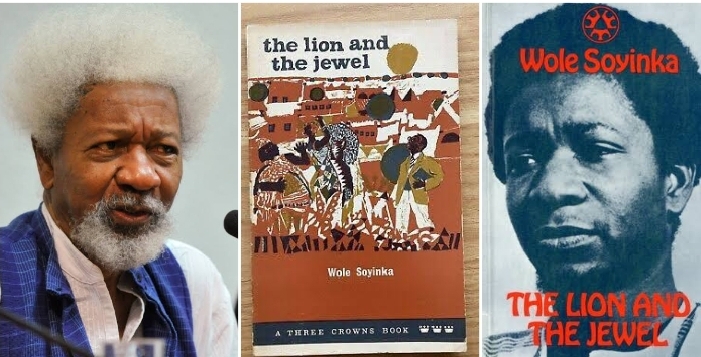

There are stories that seem complete the day they are written — until time, that most stubborn of critics, circles back to rewrite them. Wole Soyinka’s The Lion and the Jewel is one such story. Set in the fictional Yoruba village of Ilujinle, it first appeared to the world as a light-hearted satire — a play about a proud village beauty, an overzealous schoolteacher, and an aging chief who refuses to surrender to modernity.

Yet, beneath its laughter and music, something more haunting was buried — an irony that only decades of cultural change could unearth.

When The Lion and the Jewel first appeared in 1959, it seemed a playful portrait of a changing world. Yet, behind its laughter, Soyinka hid a challenge — a mirror held up to a society eager to trade its soul for the glitter of progress. What looked like satire would, in time, reveal itself as prophecy.

This is not merely a retelling of The Lion and the Jewel. It is an excavation — of the ironies Soyinka planted like seeds, the gendered riddles he left half-solved, and the cultural mirror that, even now, reflects more than the play’s characters realize. To read the play today is to discover that the true duel was never between the lion and the jewel, but between the illusions of civilization itself.

Early Sequence: When Ilujinle First Heard the Sound of the School Bell

The play opens not with conflict but with a rhythm — the slow, playful pulse of village life. Ilujinle is a world in motion, filled with the chatter of market women, the flirtation of young men, and the rustle of gossip. And yet, something foreign has arrived: a bell. Its clang cuts through the natural order, a sound imported from the West, rung by a man who believes himself sent to rescue his people from ignorance. Lakunle, with his tight European trousers and his English diction, is not just a teacher; he is an emblem of colonial mimicry, a child of mission education who believes the village must evolve by imitation.

In the early sequence, Soyinka introduces Lakunle’s obsession with progress as almost comic. He refuses to pay Sidi’s bride price because it is “barbaric,” quoting scripture and Shakespeare in the same breath. But behind the laughter lies a critique sharper than it first appears. Lakunle’s education has made him fluent in someone else’s language but deaf to his own people’s rhythm. His modernity is performative — a kind of cultural theatre that mistakes mimicry for enlightenment.

What’s remarkable is how Soyinka refuses to make Lakunle purely ridiculous. He is tragic in a small, human way — sincere, but blind. His school bell is both a symbol of awakening and intrusion. For every clang that announces literacy, another silences the oral tradition that sustained Ilujinle for generations. Soyinka, himself a product of both Yoruba wisdom and Oxford education, understood this double bind too well. The playwright doesn’t mock education; he mourns its loss of cultural humility.

As time would later prove, Ilujinle’s story was not unique. Across postcolonial Africa, the first generation of Western-educated elites struggled with the same delusion — that civilization was a ladder with the West at its top. Soyinka had already foreseen this irony in 1959: progress without roots turns men into caricatures of those they admire.

The Lion’s Shadow: Baroka and the Politics of Ageless Power

Baroka enters not as a villain but as a paradox — a man both feared and adored, cunning yet dignified. His strength is not just physical; it is intellectual in the oldest Yoruba sense — the wisdom to survive by adapting. Unlike Lakunle, Baroka does not reject modernity outright; he negotiates with it. When the Public Works Department tries to bring a railway through Ilujinle, he bribes the surveyor to divert it. To a colonial administrator, this might seem backward — but to Baroka, it is strategy. Control of change, not resistance to it, defines true authority.

In Yoruba political thought, a Bale or king is not simply a ruler but a custodian of continuity. His legitimacy depends on his ability to preserve the moral center of the community amid disruption. Soyinka knew this instinctively, and through Baroka, he captured a form of leadership that Western models could neither understand nor replace. The lion’s strength lies not in violence but in cunning — in the art of playing weakness to outwit those who underestimate him.

Decades later, the irony of Baroka’s character would ripen in meaning. Modern African politics, once expected to replace chiefs with technocrats, ended up reproducing the same pattern of cunning power. The old man in the palace became a recurring metaphor — a figure both obsolete and eternal. Soyinka’s Baroka anticipated the enduring nature of charisma in African leadership: power survives not by moral right, but by cultural resonance.

Yet, Soyinka also allows the lion’s shadow to darken. Baroka’s manipulation of Sidi — his use of desire and flattery to conquer her pride — exposes the patriarchal machinery hidden inside the charm of tradition. Here lies the play’s deepest irony: the very culture that Soyinka defends also sustains inequality. But the playwright doesn’t simplify this into modern feminist outrage; he invites readers to see how power, in every form — traditional or modern — seeks disguise.

Sidi’s Mirror: Beauty as Currency and Curse

If Lakunle represents modernity and Baroka tradition, then Sidi is the mirror in which both men see themselves. She is the “jewel” of Ilujinle, beautiful, proud, and momentarily famous after her image appears in a foreign magazine. But Soyinka refuses to let her be a mere object of desire. Sidi’s awareness of her beauty becomes her agency, her rebellion against being owned by either the old or the new. Yet, her pride also becomes her undoing — not because she is vain, but because she misreads the game.

Sidi’s story anticipates a dilemma that Nigerian women — and indeed, women across postcolonial societies — continue to face: the illusion of empowerment within structures still designed by men. Her beauty, celebrated by the village, is still a form of currency controlled by others. The photographer who takes her picture, the villagers who adore her image, and even Baroka who desires her — all participate in defining her worth externally.

When Soyinka wrote this, feminism as a global discourse had barely entered African literature. Yet, his portrayal of Sidi carries a prophetic sensitivity. She is not punished for ambition; she is ensnared by the limitations of her time. Her eventual choice to marry Baroka is not simply submission — it is survival. In Ilujinle, power lies not in the hands of those who know right, but those who understand the rhythm of the village. Baroka seduces her not with force but with myth-making; he turns narrative into conquest.

Time’s irony here is piercing. The very society that mocked Lakunle’s arrogance continues, decades later, to reenact Sidi’s surrender in subtler ways. Women’s freedom, often celebrated in urban rhetoric, still faces the same invisible walls of tradition, respectability, and survival. Soyinka’s play, seen from the distance of sixty years, becomes not a rural comedy but a social mirror — one that refuses to flatter.

The Marketplace of Modernity: When Progress Became Theatre

In the middle sequence, Soyinka stages one of his most symbolic scenes — the villagers performing the story of Sidi’s magazine fame. It is meta-theatre: a play within a play. But beneath the humor, Soyinka hides an indictment of modernity as performance. The villagers act out what they do not fully understand — a foreign photographer, a shiny camera, and a printed image that turns their world into spectacle.

This scene captures Soyinka’s genius for using Yoruba communal theatre to expose the Western gaze. The villagers laugh as they mimic the photographer’s strange movements, but the deeper laugh belongs to Soyinka — he shows how colonialism turned African life into ethnographic entertainment. Even in celebration, Ilujinle is performing itself for the eyes of others.

The marketplace in The Lion and the Jewel is not just physical; it is ideological. It represents the trade between authenticity and appearance. Lakunle sells his modern ideas like a missionary vendor, Baroka trades wisdom for desire, and Sidi barters pride for status. Soyinka turns every dialogue into a negotiation of values, revealing how easily truth becomes currency.

Over time, this scene has grown eerily relevant. In the age of social media, beauty and modernity are once again sold in the global marketplace — only now, the magazine has become a screen. What Soyinka dramatized as a village farce has evolved into digital culture. The laughter of Ilujinle echoes through Instagram feeds and influencer campaigns — proof that the irony outlived its playwright.

Mid-Sequence Reflections: Soyinka’s Unspoken Philosophy of Duality

Midway through the play, one senses Soyinka’s invisible presence — not as narrator, but as philosopher. His work, from A Dance of the Forests to Death and the King’s Horseman, always wrestled with dualities: life and death, reason and ritual, modernity and myth. The Lion and the Jewel was his earliest rehearsal of this theme.

Soyinka understood Yoruba cosmology as a theatre of balance — where opposites coexist, and contradiction is not error but truth. In Ilujinle, modernity and tradition are not enemies; they are two dancers locked in eternal rhythm. Lakunle and Baroka are not moral opposites but reflections of one another’s blindness. Each tries to define progress in his own image.

Here lies the hidden irony that time has finally understood: Soyinka was never mocking either side. He was mocking certainty itself. The arrogance of believing that civilization has a single path, that wisdom wears only one kind of clothing, that love or power can ever exist without their opposites. The play’s enduring power lies not in who wins Sidi’s heart, but in what that contest reveals about the human condition — that every ideal, when unexamined, becomes its own form of tyranny.

As Nigeria’s history unfolded — coups, corruption, and cultural awakening — the laughter of The Lion and the Jewel began to sound like a warning. The educated elite who scorned the “village ways” ended up building a modernity equally rooted in illusion. Baroka’s cunning found its echo in politicians who could outsmart entire institutions. The lion’s roar never truly faded; it only changed its accent.

Latter Sequence: The Seduction that Wasn’t About Desire

When the scene shifts to Baroka’s palace, Soyinka transforms Ilujinle’s comic theatre into psychological drama. What unfolds between Baroka and Sidi is often misread as a seduction of the body. Yet Soyinka layers it with far deeper stakes — it is the seduction of narrative control. For the first time, Sidi is drawn into the lion’s den not as prey, but as a participant in his myth-making.

Baroka’s genius lies in his ability to sense the future and script it in his own favor. He tells Sidi that he, too, was once mocked as obsolete, that the world of machines and mirrors left him behind. Yet, with disarming humility, he praises her fame, her image, her youth. He weaves into her vanity a subtle theology of flattery. What Baroka truly seeks is not love — it is the preservation of his symbolic dominance through her consent.

The supposed trick — the “false impotence” Baroka claims — is often read as comic irony. But time reveals it as a parable of power’s adaptability. The old order pretends weakness only to reinvent itself. Sidi believes she’s walking into a harmless conversation; she’s entering a ritual of succession disguised as romance. Soyinka’s stagecraft turns flirtation into metaphor. When Sidi later emerges changed — her pride softened, her independence dissolved — the audience is forced to confront not just a gendered loss, but a civilizational one.

The irony deepens with time. Decades after the play’s publication, the same pattern of seduction repeats itself in modern societies: tradition masquerades as progress, patriarchy wears the mask of respect, and every revolution ends with the same faces, older and wiser, reclaiming the throne. Soyinka’s play never needed to predict the future — it had already decoded it.

Soyinka’s Women and the Burden of Representation

To understand Sidi’s arc is to confront one of Soyinka’s most debated legacies — his treatment of women. Critics have long argued that The Lion and the Jewel enshrines patriarchy by rewarding Baroka’s manipulation. Yet, time invites a subtler reading. Soyinka was not celebrating Sidi’s submission; he was indicting the conditions that made it inevitable.

Sidi’s resistance to both Lakunle and Baroka mirrors the double bind of postcolonial womanhood. Lakunle’s modernity promises equality but denies respect for her culture. Baroka’s tradition offers belonging but demands obedience. Between them, Sidi’s freedom is an illusion. Her beauty, once a weapon, becomes her cage. When she marries Baroka, she does not so much choose as surrender to the only script available.

But Soyinka’s irony is that Sidi, in her defeat, becomes immortal. She embodies the continuity that both men seek. The village celebrates her marriage not as tragedy but as renewal. Life in Ilujinle flows on — laughter, dance, and drums erase the tension. For the audience, though, the unease remains. The music feels triumphant, but the meaning trembles beneath it. Soyinka forces us to watch the cycle repeat: the woman’s voice absorbed, the lion’s roar restored, the modern man humiliated — and yet, somehow, the play remains a comedy.

That laughter, seen from today’s lens, is no longer innocent. Feminist criticism has reframed The Lion and the Jewel as a study of performative consent — how societies script women’s choices and then call them destiny. Soyinka’s genius lies in his refusal to moralize. He does not excuse Sidi’s submission, nor condemn it. He simply holds a mirror to the audience, daring them to see themselves reflected in her silence.

Over time, that silence has spoken louder than any line of dialogue. It echoes through classrooms, film adaptations, and gender debates. Each generation of Nigerian readers discovers in Sidi a new symbol — of rebellion, of loss, of reluctant wisdom. What Soyinka wrote as comedy now reads like prophecy.

The Teacher’s Tragedy: Lakunle and the Dream that Died Laughing

No character in The Lion and the Jewel has aged more painfully than Lakunle. When he first appeared onstage, audiences laughed at his stiffness, his absurd grammar, and his eagerness to “civilize” everyone. Yet, in hindsight, he represents an entire generation’s heartbreak. The educated African, caught between admiration for the West and alienation from home, became one of postcolonial literature’s recurring ghosts.

Lakunle’s tragedy is not ignorance; it is loneliness. He cannot fully belong to Ilujinle, yet the world he imitates will never accept him. His insistence on “modern” marriage without bride price — a gesture of liberation in theory — becomes arrogance in practice because it erases cultural meaning. He confuses modernization with moral superiority.

Soyinka’s satire of Lakunle is gentle but merciless. Every word of his is a parody of colonial pedagogy — grand ideas spoken without context, “progress” without compassion. Yet, as decades passed, Lakunle’s voice began to sound familiar. He is the prototype of the Nigerian intellectual who believes English fluency equals enlightenment, who trades cultural nuance for imported ideals. In many ways, the post-independence elite fulfilled Soyinka’s warning.

When Lakunle loses Sidi, it feels almost comedic. But time reveals it as tragedy. The dream of modernization that once charmed Africa’s youth collapsed under the weight of corruption, inequality, and disillusionment. The educated class became isolated from the people they sought to lead. The same bell that rang for progress now tolls for estrangement. Soyinka’s laughter, viewed through time, becomes elegiac — a requiem for the dream that died laughing.

The Unseen Prologue: Soyinka’s World Before Ilujinle

To grasp why Soyinka wrote The Lion and the Jewel the way he did, one must travel backward — to the late 1950s, when the young playwright returned from Leeds University to a nation on the verge of freedom. Nigeria was bursting with optimism, and theatre became its mirror. Yet Soyinka, even in his youth, distrusted easy triumphalism.

He had witnessed the colonial classroom where African culture was reduced to folklore and European manners exalted as civilization. He had seen how education created distance instead of unity. In The Lion and the Jewel, he distilled these tensions into allegory. Ilujinle was not a village on a map; it was the entire country — ancient, proud, but unsure how to face the modern gaze.

Soyinka’s artistic method was never simple realism. He wrote in layers — myth folded into satire, ritual hidden inside humor. His Yoruba heritage gave him an instinct for the cyclical, for understanding that every ending is a return. In Yoruba dramaturgy, laughter is never just laughter; it is a spiritual release, a way to confront tragedy without naming it.

Thus, The Lion and the Jewel was never merely a rural comedy. It was a meditation on power, desire, and continuity disguised as farce. The irony is that audiences in 1959 saw it as charming entertainment, while readers in the twenty-first century see in it the anatomy of every African irony: freedom that reproduces bondage, modernity that mocks itself, and progress that circles back to tradition.

The Return of the Lion: How Modern Africa Rewrites the Play

Time has been the play’s most brilliant director. Over six decades, The Lion and the Jewel has been staged across continents, each version revealing new meanings. In 1970s Nigeria, Baroka was seen as a metaphor for military rulers — cunning men who claimed to protect tradition while amassing power. In feminist reinterpretations of the 1990s, Sidi became the voice of suppressed womanhood. In modern digital readings, Lakunle represents the social media activist — loud, informed, but sometimes performative.

Soyinka’s characters endure because they are archetypes of recurring history. Ilujinle never disappears; it simply relocates — from the market square to the newsroom, from the palace to parliament. The lion still negotiates progress on his own terms, the jewel still shines under borrowed light, and the teacher still waits for applause that never comes.

This is the play’s final irony: it refuses to age. Its humor ripens into warning, its satire becomes mirror. Time has not solved the argument between tradition and modernity; it has only made it more complex. The generation that mocked Lakunle now struggles with the same duality in new forms — Western technology, global culture, digital mimicry. Soyinka’s laughter, faintly sardonic, echoes through the years as if to say: You learned to ring the bell, but not to hear it.

Memory as Theatre: When History Performs Itself

There’s a subtle motif in The Lion and the Jewel that often escapes readers — performance as memory. Every event in Ilujinle is staged twice: once in life, once in reenactment. The villagers reenact Sidi’s magazine fame; Baroka reenacts his own myth to seduce her; Lakunle reenacts his idea of civilization. Through repetition, Soyinka suggests that culture is a play that never ends, only recasts its actors.

In Yoruba oral tradition, performance is not imitation but renewal. Each retelling revives the moral question at the story’s core. Soyinka applies this philosophy to modern identity: Nigeria, like Ilujinle, keeps performing its contradictions. The postcolonial state becomes a stage where the lion and the jewel continue their eternal dance — power chasing beauty, tradition negotiating with change, laughter masking unease.

Seen this way, The Lion and the Jewel becomes less a love triangle and more a cultural choreography. It’s about how societies remember themselves through ritual, even when they claim to move forward. Every technological advance, every imported ideal, is another act in the same play. The real question is whether the actors understand their script or merely recite it.

The Language of Irony: How Soyinka’s English Spoke Yoruba

Soyinka’s mastery of irony rests in his language. He wrote in English, but his English carried the pulse of Yoruba thought. The rhythm, the humor, the dramatic pauses — all are translations of oral storytelling. In his hands, English became elastic, capable of carrying proverbs without losing their native heat.

This linguistic irony deepens the play’s meaning. The same language that colonized Africa becomes the medium of its defiance. Soyinka bends English to Yoruba cadence, turning satire into resistance. His wordplay — from Lakunle’s verbose modernisms to Baroka’s sly metaphors — enacts the very cultural collision the play dramatizes.

Time has revealed the depth of this choice. In an age where linguistic identity remains political, Soyinka’s English stands as proof that colonization could not silence rhythm. The language of power became the instrument of laughter. The playwright conquered empire not by rebellion, but by irony. Every sentence in The Lion and the Jewel is both an imitation and an inversion — the colonizer’s tongue speaking the colonized soul.

When Time Became the Fourth Character

Decades after the play’s first performance, a silent fourth character has emerged — time itself. It watches over Ilujinle like an unseen god, recording what the characters cannot foresee. Every cultural victory becomes temporary, every moral certainty reexamined. Lakunle’s progress becomes vanity; Baroka’s wisdom becomes manipulation; Sidi’s beauty becomes metaphor.

Time has fulfilled Soyinka’s prophecy in the most ironic way: both modernity and tradition have betrayed their promises. Yet humanity persists, laughing through its contradictions. What Soyinka offered was not a resolution but a rhythm — the Yoruba idea that balance, not victory, sustains life.

The hidden irony that time finally understood is this: The Lion and the Jewel was never about who wins the woman, but about how civilizations court their own reflection. Every generation believes itself wiser than the last, yet finds itself repeating the same dance — proud, hopeful, deluded, alive.

Closeout: The Laugh that Outlived the Village

When the drums of Ilujinle fade, what remains is laughter — not mockery, but recognition. Soyinka, ever the trickster-philosopher, left his audience with a smile that hurts. His comedy concealed tragedy, his village disguised the world. The lion still reigns, the jewel still glows, and the teacher still waits for applause. But time, that impartial witness, has learned to laugh too — at humanity’s endless theatre of self-deception.

In the end, The Lion and the Jewel is not a play about Africa’s past, but its perpetual present. It is about how every society, in chasing progress, ends up reenacting its origins.

Soyinka’s irony has matured into timelessness. What once seemed a village farce has become a mirror for nations, lovers, thinkers — all chasing the shimmer of the jewel, unaware that the lion is always watching, smiling, waiting for the next act to begin.

Discussion about this post