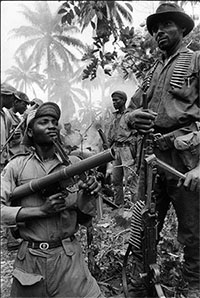

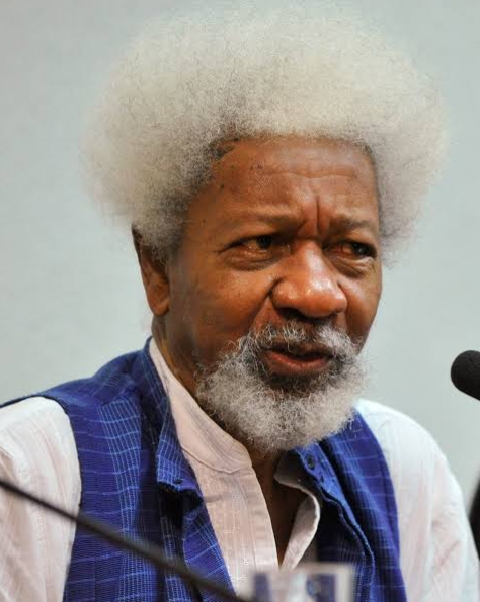

The echoes of 1967 still hang in the corridors of Nigerian memory, a weight that bends the light of the present. Even decades later, conversations about Biafra are neither casual nor harmless; they tread into a territory of old grief and unresolved guilt. Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, with her essays and reflections, has once again threaded herself into this delicate terrain, her words stirring dialogues that linger like ghosts. For Wole Soyinka, the Nobel laureate who bore the burden of witness during the war, the renewed debates are not just historical—they are personal, a reminder of a time when conscience and country collided.

Nigeria’s post-war society has tried, often inadequately, to reconcile the story of Biafra with its own national identity. Adichie’s writing, literary and piercing, revives the questions that many thought were settled, challenging the country to confront memories that refuse to rest. The tension between memory and narrative, between history and interpretation, is where the heart of this story beats.

The essays and interviews that Adichie has offered over the past decade do more than recount events—they interrogate the legacies of war, identity, and moral responsibility. Each phrase she writes, each historical analogy, carries the weight of a nation still learning to speak of itself without faltering. For Soyinka, who stood as a moral and intellectual witness during those years, such reflections inevitably reopen debates that are both public and intimate.

As this narrative unfolds, it explores the intersections of literature, memory, and moral reckoning in Nigeria. It asks what it means for writers and thinkers to revisit trauma, how the personal and collective intertwine, and why certain debates refuse the solace of closure. Across these lines, the story of Adichie and Soyinka converges, a literary and historical dialogue echoing across generations.

Biafra and the Weight of Memory

The Nigerian Civil War, which erupted in 1967 and concluded in 1970, left scars that are still raw in both the psyche and politics of the nation. While textbooks present dates and casualties, the lived experiences of those who endured the war are layered with suffering, displacement, and moral ambiguity. Adichie’s reflections bring these layers into sharp relief, demanding that modern readers confront a past that is at once uncomfortable and instructive.

Wole Soyinka’s engagement with the war was fraught with peril. He navigated a landscape of ideological extremes and political danger, risking imprisonment and exile. His writings and speeches from that period are marked by a painstaking effort to articulate both ethical and historical clarity. Adichie’s essays, written decades later, resonate with that same urgency: a recognition that history cannot be sanitized, that moral reckoning is ongoing.

The legacy of Biafra is more than political; it is cultural, psychological, and artistic. Nigerian literature, music, and art continue to grapple with the reverberations of the war. Adichie’s work, like Soyinka’s before her, situates storytelling as a means of navigating trauma. Yet, the generational shift in her perspective allows for a dialogue that is simultaneously contemporary and reflective, bridging the space between memory and imagination.

For Soyinka, revisiting these debates—even indirectly through Adichie’s work—can be a form of confrontation with the ghosts of his own choices and observations. The tension is not antagonistic, but reflective, a reminder that history lives in the minds of those who remember it most vividly. Through this lens, literature becomes a battlefield of ideas where empathy, truth, and responsibility intersect.

Wole Soyinka’s Reflections on Biafra — Bearing the Moral Weight of Memory

The echoes of Biafra linger like a shadow cast long after the sun has set. Wole Soyinka has often walked these shadows, tracing the contours of history with the patience of one who bears witness. His reflections are neither simplistic nor partisan; they are a meditation on humanity, belonging, and the moral debts of a nation.

Recognition of Igbo suffering: Soyinka affirms that the Igbo people endured extreme wrongs, stating he is “very much pro‑Biafra” in recognizing that they “have been so wronged that they have no choice than to consider opting out of Nigeria.” He sees in their suffering not abstraction, but a wound that history cannot disguise.

Acknowledgment of complexity: While acknowledging that the Igbo or Biafrans were “not entirely innocent in this affair,” Soyinka insists that the scale of devastation justifies their sense of alienation. History, he notes, rarely presents in black and white; its truth is layered and often uncomfortable.

The war is not over: Soyinka warns that defeat is not final: “Biafra has not been defeated, only war tactics changed.” Memory, like a river under the earth, continues to flow even when the surface appears calm.

The danger of forgetting: Officials may refuse to confront history, he says, yet “if you do not confront your past, you are going to mess up your future.” Amnesia, he implies, is the quiet enemy of nations.

Belonging and alienation: The question of inclusion resonates through his reflections: “What can we do to make Igbo feel they belong, not alienated?” He suggests that slogans like “Nigeria is indivisible” are hollow if they fail to bridge the chasm of lived experience.

Agitation for humanity: Soyinka rejects narrow nationalism: “I don’t agitate on some certain entity called a nation; I agitate on humanity.” His moral compass points not to flags or borders, but to conscience itself, and the ethical responsibility of every citizen.

Soyinka’s reflections thus occupy a space where history, ethics, and literature converge, offering a landscape both jagged and luminous—a terrain of moral reckoning in which every citizen must navigate the delicate balance of witness and memory.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Reflections on Biafra — Reawakening Memory and Dialogue

Chimamanda Adichie approaches the legacy of Biafra like a cartographer of the human spirit, mapping its contours through words and empathy. She recognizes that the war’s shadows stretch into the present, shaping identity, politics, and the unspoken burdens carried by those who survived and their descendants.

Persistent divisiveness: Adichie notes that the war remains divisive decades later: “It’s still very divisive… sometimes you bring up Biafra, and immediately you’re labeled a troublemaker.” The silence surrounding these memories is itself a form of tension, a fragile crust over smoldering history.

Necessity of truth-telling: For Nigeria to heal, Adichie argues, historical acknowledgment is vital: “I think we should have a sort of Truth and Reconciliation Committee … because it is impossible to understand Nigeria without understanding her history from around 1965 to 1970.” Without such reflection, society risks repeating moral oversights.

Pragmatic politics over slogans: While sympathetic to the sense of marginalization driving some independence movements, she challenges the notion that secession is the solution: “Where would the border be? … what is propelling all those movements is a sense of marginalisation which I think is completely valid. … But this idea that the answer is independence is what I’m not convinced of.” Her lens is careful, rational, and rooted in structural reality rather than symbolic gestures.

Highlighting structural injustice: Adichie emphasizes ongoing post-war inequities: “There were houses in Port Harcourt today … illegally taken from their owners … that is injustice that has not been addressed.” Her reflections foreground tangible consequences, not only abstract debates.

Clarifying her stance: She distances herself from misattributed activism, asserting she did not write certain pro‑Biafra articles and has not declared, “I am a Biafran and nothing else.” Her engagement is intellectual and moral, not performative or polemical.

Through these reflections, Adichie positions herself as a narrator of moral landscapes, drawing lines between past and present, memory and justice, personal empathy and national consciousness. Her prose becomes a lens through which readers can perceive the enduring tensions of Biafra—not as a distant event, but as a living, breathing dialogue across generations.

Literature as Memory’s Vessel

History, for Nigeria, is rarely contained in archives or government statements; it moves like wind through the cracks of buildings, whispered in corridors, memorialized in literature. Both Soyinka and Adichie have recognized that storytelling is not merely a form of entertainment—it is a vessel that carries memory, responsibility, and moral reckoning.

Soyinka’s literary witness: From the plays and essays written during the Biafran War to reflections in later decades, Soyinka transforms observation into moral inquiry. His works bear the weight of ethical accountability, forcing readers to confront human failure and resilience simultaneously. The war is not a plot point; it is a crucible in which conscience and society are tested.

Adichie’s narrative empathy: In her essays and interviews, Adichie reconstructs the human consequences of Biafra with precision and care. She elevates stories of displacement, hunger, and marginalization into collective memory, reminding readers that history is not abstract but lived. Through this, literature becomes a bridge connecting past trauma to contemporary reflection.

The dialogue across generations: By engaging with the war through literature, both writers create a conversation that spans decades. Soyinka’s moral urgency echoes in Adichie’s narrative approach, while her contemporary lens refracts his experience into fresh relevance. The act of storytelling becomes a conduit for understanding, one that refuses to let memory settle quietly.

Moral and aesthetic fusion: Literature, in this context, is both art and ethical inquiry. Every character, every metaphor, every essay functions as an argument for remembrance, empathy, and justice. For readers, the experience is immersive: the war’s shadows are not explained—they are felt, traced, and confronted.

Through literature, Biafra is never fully past; it is continually reinterpreted, its moral lessons revisited, its human stories preserved. Soyinka and Adichie remind Nigeria that memory is an inheritance, demanding attention, reflection, and sometimes discomfort.

Cultural Memory and National Identity

The war left a fracture in Nigeria’s sense of itself, a fissure through which questions of belonging, justice, and national identity persistently emerge. For both writers, the task is not simply to recount events but to illuminate how the past shapes the present, coloring perceptions of inclusion and alienation.

Soyinka on alienation: He asks, “What can we do to make Igbo feel they belong, not alienated?” The question underscores a national identity still in negotiation, where rhetoric often eclipses lived reality. Alienation, in Soyinka’s view, is the true danger—one that can fester across generations if left unaddressed.

Adichie on acknowledgment: She emphasizes that understanding Nigeria requires grappling with 1965–1970, arguing for mechanisms like a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. History, unacknowledged, becomes a ghost that shapes policy, attitudes, and communal relationships long after the fighting has ceased.

Intersection of memory and narrative: Both writers situate identity in stories. Soyinka’s moral witness and Adichie’s narrative empathy converge to suggest that national consciousness is inseparable from collective memory. A nation that forgets its past cannot fully claim its present.

The tension of reconciliation: Cultural memory is contested, not static. Debates over Biafra are both historical and contemporary, a living dialogue over what it means to belong, who is included in the national narrative, and how justice is conceived. Literature becomes a tool for this dialogue, allowing ethical and historical tensions to surface in ways public discourse often cannot.

Ethics of Storytelling and Historical Responsibility

To tell the story of Biafra is to assume responsibility—not only for facts, but for empathy, accuracy, and moral engagement. Both writers recognize that narratives carry weight, shaping not only understanding but conscience.

Soyinka’s ethical imperative: For Soyinka, literature is inseparable from morality. His reflection that “Biafra has not been defeated, only war tactics changed” signals an ongoing duty to confront injustice, not simply recount events. Stories are not neutral; they are instruments of witness.

Adichie’s narrative precision: Adichie carefully frames history to avoid myths or oversimplification, highlighting structural injustices and ongoing marginalization. She acknowledges tensions but resists reductive explanations, emphasizing moral clarity over sensationalism.

Narrative as dialogue: Both writers understand that storytelling is not a monologue. Adichie’s essays resonate with the echoes of Soyinka’s observations, creating a cross-generational conversation in which ethical reflection is as important as historical analysis.

The moral stakes of forgetting: The act of writing, of narrating, is also an act of ethical resistance against collective amnesia. Without careful storytelling, the past becomes vulnerable to distortion or erasure. Literature, in this context, is both shield and compass, guiding readers through moral and historical complexities..

The Unfinished Dialogue Between Past and Present

History never rests quietly; it whispers through generations, demanding attention and reflection. For Nigeria, Biafra is not a chapter neatly closed but a persistent echo in public consciousness and private memory. The reflections of Soyinka and Adichie serve as a bridge across time, linking the witnesses of the war with the inheritors of its legacy.

Soyinka’s temporal echo: By asserting that “Biafra has not been defeated, only war tactics changed,” Soyinka reminds the nation that memory is alive, and unresolved injustice is never inert. His voice reverberates through decades, a moral compass in a society often tempted to look away.

Adichie’s generational lens: Adichie translates the echo for a contemporary audience, situating the war’s aftermath within present-day realities: political marginalization, structural inequities, and the lingering sense of injustice in Igbo communities. Her lens refracts Soyinka’s moral urgency into a conversation that speaks to younger generations navigating identity and history.

Cross-generational dialogue: Literature becomes the medium of this dialogue. Soyinka’s moral witness intersects with Adichie’s narrative empathy, creating a layered discourse that is both literary and ethical. The past speaks to the present, and the present listens, interpreting, questioning, and remembering.

Memory as active force: This dialogue demonstrates that history is not static. It informs national consciousness, shapes identity, and influences political and cultural choices. In Nigeria, forgetting is dangerous; engaging with memory is necessary for any hope of reconciliation, unity, or justice.

Biafra’s Shadow in Contemporary Politics

The echoes of 1967–1970 are visible in the political landscape of Nigeria today. From debates over federalism to discussions about minority rights, the civil war’s unresolved questions permeate contemporary policy and public discourse. Literature and historical reflection provide critical tools for understanding these dynamics.

Soyinka on belonging: Soyinka’s repeated question about alienation—“What can we do to make Igbo feel they belong?”—resonates in debates over political representation, federal appointments, and equitable resource distribution. His reflections illuminate the persistent structural inequalities that continue to affect national cohesion.

Adichie on marginalization: Adichie highlights post-war structural injustices, including property dispossessions and political exclusion. Her observations connect historical trauma to contemporary challenges, showing how unresolved grievances shape political behavior and community sentiment.

Narrative as civic compass: By documenting and analyzing the human and ethical dimensions of the past, literature functions as a guide for policymakers and citizens alike. Stories, memoirs, and essays become instruments for ethical reflection and civic engagement.

Lessons for contemporary governance: Understanding the legacy of Biafra through these reflections can help Nigeria develop mechanisms for inclusion, reconciliation, and equitable governance. Historical awareness, paired with moral consideration, remains essential for addressing contemporary conflicts.

Lessons from Literary and Moral Reflection

When moral witness meets narrative craft, history gains both texture and ethical gravity. Soyinka’s and Adichie’s reflections are instructive, showing how literature can illuminate moral truths, reveal systemic failings, and guide collective reflection.

Ethical engagement: Both writers insist that acknowledging the past is not optional. History is a moral terrain, and stories are instruments for ethical reckoning. Silence or evasion risks perpetuating injustice.

Humanized memory: Adichie’s narrative empathy humanizes abstract statistics and events, while Soyinka’s moral witness frames the ethical implications. Together, they create a map of memory that is both visceral and analytical, guiding readers through the human dimensions of history.

Bridging generations: By connecting the lived experience of the war with contemporary reflection, they facilitate intergenerational dialogue. Younger Nigerians can understand the stakes, the human suffering, and the moral challenges that shaped national consciousness.

Call to reflection: Literature, they show, is both mirror and lamp. It reflects society’s failures and illuminates paths toward understanding, empathy, and justice. For Nigeria, engaging with Biafra through such reflective lenses is an act of civic responsibility and moral courage.

The Debates That Never Sleep (Reflective conclusion)

Some questions refuse to rest. Biafra is one of them. Soyinka once carried its weight alone, pacing the moral corridors of memory while a nation pretended the echoes were gone. Today, Adichie stirs those same shadows—not to resurrect old grievances, but to insist that history still speaks, that the conversations never ended, that the nation cannot escape the truths it refuses to name.

Their reflections converge across decades, not in agreement, but in insistence: that justice, memory, and conscience are not optional. What they reveal is less about Biafra as a war, and more about Biafra as a question of humanity—a question every Nigerian inherits whether they acknowledge it or not.

The debates linger because the story lingers. They haunt not for the sake of nostalgia, but because forgetting is impossible. In reviving these discussions, Adichie does more than echo Soyinka—she confronts a nation with its unfinished reckoning. And in that confrontation, the past is not past, the wounds are not silent, and the dialogue is unstoppable.

History, once spoken, never sleeps.

Discussion about this post