There’s a silence that settles over Lagos at midnight — not the quiet of rest, but the hum of forgotten sounds. Somewhere beyond the Third Mainland Bridge, a film reel curls into itself in a storage room no one visits anymore. Old music masters once spun inside that reel, their laughter trapped between layers of dust and magnetic tape. In Lagos, history isn’t lost in war or flood; it simply fades beneath the rhythm of survival. The city grows, but its memory recedes.

Every generation in Lagos inherits a city louder than before. From the colonial halls of Marina to the neon corridors of Ikeja, Lagos builds and rebuilds itself in haste. Yet, beneath its concrete skin, fragments of its soul still pulse — letters unfiled, negatives undeveloped, vinyls unplayed. The past lives quietly in forgotten rooms: in the dark backstage of Glover Memorial Hall, in the boarded-up projection booth at the old Rex Cinema, in the rusting tape recorders behind a defunct radio station in Yaba. Each is an archive — not merely of documents, but of the city’s heartbeat.

When the final door closes on these archives, what will Lagos remember? The city that gave birth to Nigeria’s first motion picture, first independence speech, and first global music sound now teeters between remembering and rewriting itself. This is not just a story of loss — it is a portrait of how Lagos, Africa’s loudest metropolis, struggles to keep its own echoes alive.

Glover Memorial Hall: The First Curtain and the Fading Light

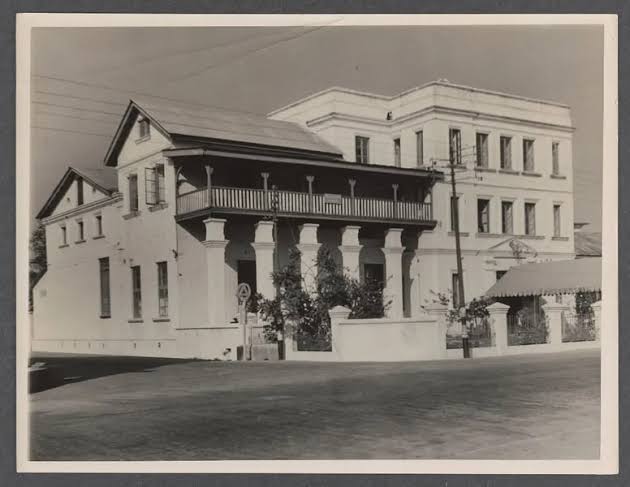

Before cinemas and concert arenas, there was Glover Memorial Hall — a stately Victorian structure erected in 1887. It was the stage upon which colonial officers hosted piano recitals, the same hall where, in August 1903, Nigeria’s first film flickered onto a white sheet stretched against the wall. There, the moving image arrived in Lagos long before Nigeria knew it would become Nollywood’s ancestral home.

Today, the Hall stands on Custom Street, dwarfed by banks and concrete towers. Its façade is faded, its stage half-lit, yet the ghosts of that first audience — civil servants, expatriates, local elites — seem to hover near the balcony. Many Lagosians pass it daily without knowing its claim to fame. The story of Nigeria’s cinematic beginning, buried within colonial logs, is slowly vanishing with the building’s paint.

The paradox of Glover Hall mirrors Lagos itself: a city that remembers selectively. While new cinemas flood shopping malls, the structure that once carried the nation’s cinematic genesis languishes, uncelebrated. The Lagos State government has promised restoration more than once; each promise fades with the next election cycle. Still, the Hall breathes — not through its preservation, but through the stubbornness of memory itself.

Every city has a monument to its imagination. For Lagos, that monument is decaying in real time. The first curtain has long fallen; only the dust performs now.

Freedom Park: A Prison Rewritten as a Poem

If Glover Hall marked the beginning of performance, Freedom Park marks the rebirth of memory. Built on the site of the old Broad Street Prison — where colonial authorities once caged activists and nationalists — Freedom Park is Lagos’s most poetic transformation of space. Its amphitheatre stands where the gallows once did; its cafés now serve drinks where prisoners once whispered to walls.

Walking through the park today, it’s easy to forget that this place was once synonymous with dread. Tourists take photos against murals of liberty, unaware that beneath their feet lie the foundations of confinement. Yet, this contradiction is precisely Lagos’s character — the city doesn’t erase history; it remodels it into metaphors.

The park’s founder, architect Theo Lawson, envisioned it as a sanctuary for remembrance — a space where art could converse with history. And in many ways, it works. Musicians, poets, and dramatists gather there to reclaim what the prison denied: voice. Yet even Freedom Park faces a subtle amnesia. Its plaques are fading; its archives are shrinking. The oral testimonies of former prisoners have not all been digitized. Without care, the park too could become another monument to forgetting — a beautiful stage, hollowed of its soul.

For now, though, the laughter that spills from its open-air concerts offers Lagos a rare thing: memory with rhythm.

The National Theatre: Where the Future Once Lived

In 1977, during the World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture (FESTAC ’77), the National Theatre rose like a spaceship from the swamp of Iganmu — a gleaming white structure shaped like a military helmet, a symbol of unity and cultural ambition. For one moment, Lagos was the global capital of black creativity. Writers, filmmakers, and dancers from across the continent converged there, and Nigeria stood proud, its oil wealth channelled into artistic grandeur.

Decades later, the Theatre stands as both masterpiece and mausoleum. Its vast halls echo with emptiness, its corridors smell of rainwater and disuse. The dream of FESTAC — to make Lagos the cultural axis of Africa — now survives only in photographs. The government’s proposed revamp in partnership with foreign investors has stirred controversy: Can a space built for collective cultural memory survive commercialization?

The Theatre’s story is the story of Lagos’s paradox: a city that builds monuments faster than it can preserve them. Where art once united the continent, bureaucracy and neglect now divide stakeholders. Yet, if you stand before the Theatre at dusk, as the sky stains orange over the lagoon, you can still feel the vibration of drums long gone silent. It’s not nostalgia; it’s a reminder that Lagos once believed in permanence.

Cocoa House and the Architecture of Aspiration

In Ibadan, less than two hours away, stands Cocoa House — West Africa’s first skyscraper and a physical echo of Nigeria’s agricultural might. But its connection to Lagos is symbolic: many of the investors who funded Cocoa House were Lagos businessmen dreaming of a modern West African metropolis. Completed in 1965, it rose from cocoa wealth and ambition — an architecture of optimism that mirrored Nigeria’s post-independence confidence.

When it caught fire in 1985, the inferno felt like an omen. A generation that once believed in growth now confronted decay. Yet, the tower was rebuilt — not perfectly, but defiantly. Lagos watched as Ibadan restored its pride, a reflection of what Lagos itself struggles to do: rebuild its memory without erasing its scars.

From Marina to Broad Street, Lagos’s skyline tells a similar story: ambition outpacing preservation. Many colonial structures have vanished, replaced by glass and steel with no memory. Cocoa House endures as a mirror of Lagos’s unfinished dream — a testament that not every fall is final, but every rebuild carries a fragment of what was lost.

The New Afrika Shrine: Faith in the Rhythm

If Glover Hall gave Lagos its first performance and the National Theatre gave it grandeur, the New Afrika Shrine gave it a conscience. Built by Femi Kuti in Ikeja as a modern replacement for his father’s original Shrine in Mushin, the venue remains a cathedral of resistance — where Afrobeat became both sermon and protest.

Unlike most Lagos monuments, the Shrine is alive. It breathes, sweats, argues, dances. Here, memory is not curated; it is improvised nightly. The Shrine doesn’t store history — it performs it. Photographs of Fela hang beside stage lights, their gaze almost prophetic. The walls remember more speeches than the archives of Nigeria’s National Assembly.

And yet, even this living archive faces its own fragility. The urban sprawl of Ikeja creeps closer; gentrification threatens the area’s raw authenticity. Cultural spaces like this often become sanitized once they gain global attention. The Shrine’s legacy depends not just on Femi and Made Kuti’s music but on Lagos’s decision to let rebellion exist without permission.

For now, the Shrine’s pulse endures — a heartbeat refusing digitization.

When Memory Became Data

Across Lagos, a new form of forgetting is taking place — not through fire or neglect, but through digitization without context. The city’s cultural institutions are scanning, uploading, and “preserving” thousands of records. Yet, without proper metadata, human testimony, or oral interpretation, memory becomes mere data. A digitized photograph without a story is just a file.

At the National Archives in Yaba, boxes of newspapers and manuscripts crumble faster than they can be scanned. The technicians do their best, but power cuts and inadequate funding mean that the future of Lagos’s past depends on chance. The irony is sharp: the more digital Lagos becomes, the more analog its amnesia grows.

Lagos’s creative scene thrives online — in podcasts, YouTube documentaries, and Instagram retrospectives — but few of these link back to the real archives that birthed them. The city now documents its culture in pixels, not paper; in hashtags, not heritage. If the last archive door closes, Lagos will still have data, but will it still have memory?

Eko Hotel and the Performance of Power

Eko Hotel has always been more than a hotel. Since its construction in 1977, it has been Lagos’s performance of power — the place where deals, coronations, award shows, and reconciliations play out. The Oba of Lagos dining under chandeliers beside pop stars and politicians encapsulates Lagos’s spirit: where tradition and modernity share the same table.

But even the grandeur of Eko Hotel is part of a larger illusion. Beneath the glamour lies a city constantly rewriting its narrative to fit the expectations of the present. The photographs from the 1980s — of Sunny Ade’s concerts, of visiting presidents, of Miss Nigeria pageants — sit locked in private collections. Few have been publicly archived. Lagos’s elite spaces preserve history only for those who can afford nostalgia.

As newer hotels rise along Victoria Island, the original Eko still commands symbolic gravity. It reminds Lagos that its identity has always been theatrical — a place where memory is curated for spectacle. The archives of Eko are not public, yet every event held there adds a new, unseen chapter to Lagos’s biography of power.

The Disappearing Sound of the City

Lagos once hummed with analog life — typewriters clacking in newspaper offices, radio tapes spinning at FRCN, street photographers developing film under the bridge. Today, that mechanical rhythm is gone, replaced by the quiet efficiency of screens. Modern Lagos remembers through algorithms; it searches instead of archives.

The danger is not that Lagos forgets — it’s that it remembers selectively. Certain eras, voices, and communities never enter the official record. The city celebrates its music but neglects its sound engineers; it honors its independence heroes but forgets the archivists who preserved their voices on tape. In the politics of memory, Lagos’s unsung custodians remain invisible.

Yet, hope survives in unlikely corners — a photographer at Jankara Market digitizing family portraits; a librarian at the University of Lagos quietly labeling 1950s microfilms; a blogger mapping the graves of forgotten artists. They are the guardians of what the city refuses to lose. When the last archive door closes, it is these hands — not the bureaucrats’ — that will keep Lagos alive.

Between Memory and Myth

Lagos has always lived on the threshold between what happened and what was imagined. Its myths often become its memory: the fisherman who founded Eko, the white horse of the Oba’s procession, the never-ending traffic that supposedly never sleeps. Each story becomes truth through retelling.

Perhaps that is why Lagos never completely forgets — it just converts memory into myth. Glover Hall becomes the ghost stage; Freedom Park becomes the poetic prison; the National Theatre becomes the lost spaceship of culture. The city might lose its documents, but it will never lose its drama.

Memory, in Lagos, doesn’t end with the archive. It continues in the voices of conductors shouting “CMS! Obalende!” at dawn; in the painters on Lagos Island reimagining FESTAC ’77 murals from memory; in the children dancing to Fela’s lyrics without knowing their political roots. When formal memory fails, folklore resumes its duty.

Final Thoughts: When the Last Archive Door Closes

One day, someone will try to open a door in Yaba or Marina and find only emptiness — papers turned to dust, film reels discolored, hard drives unreadable. The last archivist will log out for the final time, and Lagos will be left with its most powerful possession: collective imagination.

For in Lagos, forgetting is never total. The city does not lose its past; it transforms it. It translates memory into music, history into performance, loss into laughter. Each generation rebuilds the archive through art, song, and story. Perhaps that is what Lagos will remember — not the documents themselves, but the relentless human desire to keep singing even after the record ends.

When the last archive door finally closes, Lagos will not fall silent. It will hum, faintly but defiantly, like a record still spinning on a broken turntable — because memory, in this city, was never meant to stay still.

Discussion about this post