Long before the microphones and vinyl sleeves, before Nigeria’s airwaves carried his name like a whisper from the Middle Belt, Bongos Ikwue walked alone. It was evening in Otukpo, Benue State. The dry-season wind carried the smell of dust and palm kernels, and a young man—then barely out of school—was following the path that wound through the forest behind his family’s compound. He wasn’t looking for a song. He was simply walking, humming something half-formed, as if the earth itself were breathing back a melody.

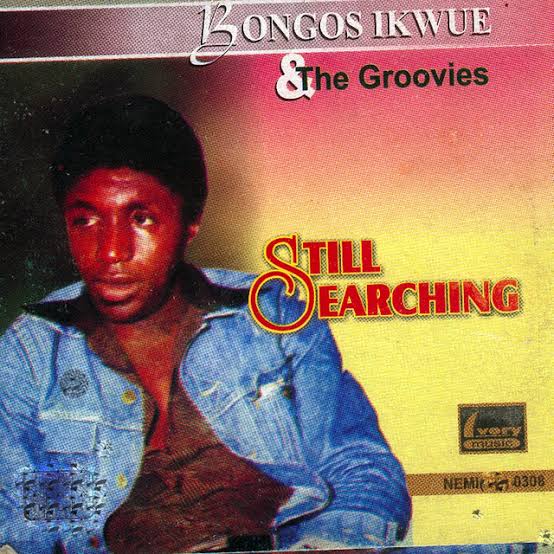

No one could have known that walk would become a parable in Nigerian music history: how a man listening to nature would later make a nation listen to itself. His footsteps sank into red soil that had carried generations before him, yet his mind was elsewhere—chasing a rhythm only he could hear. That rhythm would later find its voice in Still Searching, one of the most enduring songs ever recorded in Nigeria. But at that moment, in the hush of trees, it was only silence answering silence.

When people speak of Bongos Ikwue, they often recall the warmth of his voice, the gentle protest of his lyrics, or his refusal to let fame erode authenticity. Few remember the forest—his first studio of solitude. In that quiet expanse, music wasn’t composed; it was discovered. What he found there was not merely a tune but a worldview: that nature is both composer and audience, that sound is born from listening before it is performed.

He would later say that he always believed every melody already existed in nature—that the duty of the musician was to find it and give it form. That belief was what turned his long walks into encounters with destiny, transforming silence into legacy.

The Boy Who Listened to the Ground

Born in 1942 in Otukpo, in the heart of Idoma land, Bongos Ikwue grew up in a world where songs carried wisdom. His mother sang folk chants as she worked, his uncles told stories in rhythm, and drums served as both communication and ceremony. In a community where identity was shaped by oral tradition, the young Bongos learned that music was not entertainment—it was continuity.

His early education took him from the red earth of Otukpo to Kaduna and later to the Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, where he studied business administration. But even as he learned the logic of numbers, his heart remained tuned to the irregular rhythm of human emotion. He joined a small music group during his university years, singing after lectures, performing at student gatherings. His voice—warm, reflective, unhurried—carried something different from the exuberant pop of Lagos or the coastal highlife of the East. It sounded like the interior of the country: thoughtful, patient, rooted.

While others sought fame through noise, Bongos sought meaning through melody. He was fascinated by how traditional Idoma songs used repetition to mirror the movement of life—how a phrase could bend with emotion yet remain anchored by truth. Those early lessons formed the template for his lifelong approach: every song must carry a message that survives the rhythm that bears it.

During holidays, he returned to Otukpo and spent hours walking beyond the village, through fields and forests. He said he loved the way the wind seemed to answer when he hummed. “That was where songs came to me,” he would later tell journalists. It was in those moments—away from classrooms and crowds—that he realized music could be a form of prayer.

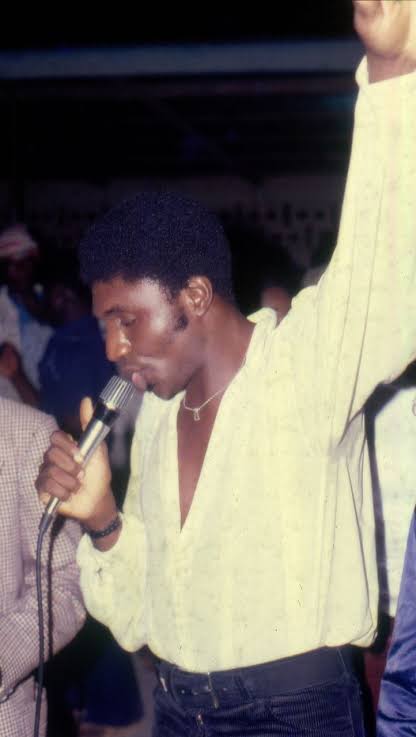

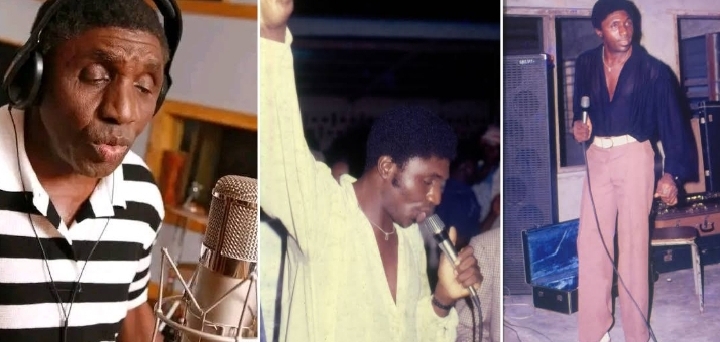

When Sound Found a Shape

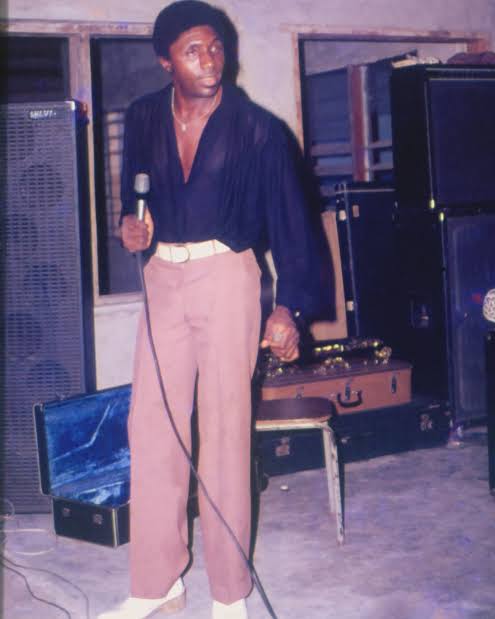

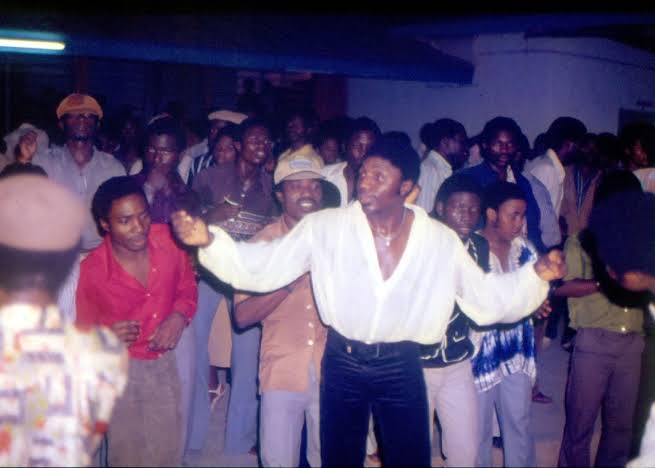

By the late 1960s, Nigeria was changing fast. Independence had come with optimism, but civil war was tearing the country apart. In that climate of uncertainty, Bongos formed The Groovies, a band that carried his reflective style into nightclubs and hotels across the country. His songs weren’t the loud celebrations of city life; they were meditations on longing, integrity, and the fragility of peace.

The walk through the forest that became a song happened around this time. One morning, while visiting Otukpo, he took his usual path through the trees near the river. The war was still raging in the east, and news of losses reached even the remotest towns. He recalled the sense of helplessness that hung in the air. “I walked,” he once said, “because when I walk, I think clearly.” As he moved deeper into the quiet, he began to hum a line that had haunted him for weeks: Still searching, still searching for love.

The phrase had no structure yet, but it carried emotion—the yearning of a generation caught between broken promises and lost innocence. As he walked, birds answered in intervals, the wind rustled in minor keys. He noticed how the forest seemed to complete the line for him. By the time he returned home that evening, the melody was complete.

When he recorded Still Searching with The Groovies in Lagos a few years later, the song carried that same reflective cadence. It wasn’t written for commercial radio; it was written as confession. Yet it resonated with millions because its theme—of seeking meaning in a confusing world—was universal. The forest had translated into a national feeling.

The Birth of a Sound Between Cultures

Bongos Ikwue stood at an intersection of identities: Idoma by birth, Nigerian by conviction, global by influence. His sound combined the folk sensibilities of the Middle Belt with the harmonic sophistication of American jazz and soul. This fusion gave his music a rare quality—both local and timeless.

When Cockcrow at Dawn was released in the early 1980s, it became more than a soundtrack to a television series; it was a hymn to national rebirth. The song carried echoes of that first walk—soft acoustic guitar, the whisper of nature embedded in the rhythm. It felt like morning itself was singing. Nigerians across regions recognized in it a familiar hope: that every dawn, however fragile, promised renewal.

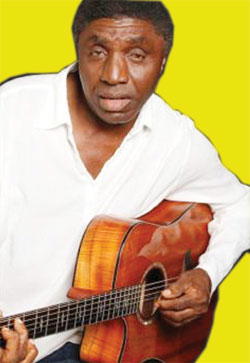

In interviews, Bongos described himself not merely as a musician but as a messenger. “Music,” he said, “is what keeps us connected to what we might forget.” He insisted on live instrumentation even when synthetic beats dominated the 1990s, believing that real sound carried the pulse of real life. His studio in Otukpo became a sanctuary for younger musicians who wanted to learn the old discipline of patience and listening.

Each chord he played was a continuation of that forest walk—proof that inspiration was not a single event but a lifetime practice. The forest had given him a method: listen, wait, then speak softly.

The Years of Silence

Every artist faces a season when applause fades. For Bongos, that silence came in the late 1990s. The new generation was dancing to faster beats, digital production replaced acoustic intimacy, and record labels no longer invested in philosophical lyrics. Yet Bongos didn’t call it retirement; he called it reflection.

He returned to Benue, built his own home and studio, and began to record again at his own pace. The quiet years revealed a man content to be misunderstood. He no longer sought chart positions; he sought continuity. His reclusive lifestyle made many think he had faded, but in truth, he was watching the country evolve, quietly composing songs that would speak to the spirit rather than the market.

When he finally released Wulu Wulu and Abayilo, they carried that unmistakable wisdom of stillness. His music had matured into something closer to philosophy. Critics began to describe him as the “sage of Otukpo,” the man who could turn everyday moments into reflective anthems. And through it all, he never abandoned the forest. He often said he still took his evening walks, still listening for songs hidden in the wind.

Between Earth and Memory

To understand Bongos Ikwue is to understand a man who sees no boundary between the physical and the spiritual. His forest walks were never mystical rituals; they were acts of observation. Yet, in those simple acts, he tapped into something profound—the belief that creativity requires communion with silence.

In Idoma culture, the forest is both refuge and archive. It stores the memory of ancestors and the sounds of continuity. Bongos transformed that heritage into melody. Each lyric carried the dignity of his people’s voice: calm, proud, enduring. His songs often carried proverbs disguised as love lines. “Still searching for love” could mean still searching for peace, or still searching for meaning. It was layered truth, accessible yet eternal.

His relationship with the land also reflected his larger philosophy of self-reliance. He refused to move permanently to Lagos or abroad despite opportunities. “Home is where the heart learns humility,” he said in a 2016 interview. That humility grounded his art and made his lyrics sound less like performances and more like conversations with time.

When younger musicians like Tuface Idibia—also from Benue—spoke of Bongos, they described him as a guardian of authenticity. His influence could be heard in the melodic patience of modern Afro-soul, even if many didn’t realize its source.

The Legacy of Listening

Today, when Nigerian music dominates global charts, Bongos Ikwue’s story reads like a reminder that progress should not erase roots. His journey from forest walks to national fame shows that innovation is often born from introspection, not spectacle.

In seminars and retrospectives, scholars now study how his lyrics predicted the socio-political anxieties of later decades: alienation, corruption, loss of communal values. Yet beyond analysis, there’s something simpler—his work teaches that beauty is inseparable from attention.

That is the deep lesson of his forest walk: in a noisy world, creation begins with silence. While others shout to be heard, the wise listen until the earth sings back. His life proves that art, when anchored in sincerity, can outlast fashion. Even now, when Still Searching plays on radio, it sounds neither dated nor nostalgic—it sounds current, as though the walk never ended.

The same wind that brushed his face that evening in Otukpo still moves through Nigerian air, carrying fragments of his melody. And perhaps somewhere, another young artist is walking through the forest, humming without knowing that he is retracing Bongos Ikwue’s steps.

The Song that Keeps Walking

Bongos Ikwue’s later years have been marked by honors, retrospectives, and renewed recognition. Yet, for him, the highest tribute remains invisible—the continuity of the song itself. Each time Cockcrow at Dawn opens a radio program, or Still Searching finds new listeners online, the melody continues its journey, crossing decades like footsteps on familiar ground.

He once said that every true song has legs—it keeps walking long after its maker rests. That is perhaps the meaning behind his forest origin story. The forest doesn’t end; it expands, regenerates. So does his legacy.

For young artists seeking fame, his life offers a counter-narrative: that greatness lies not in speed but in depth, not in exposure but in endurance. His music teaches the power of stillness, patience, and authenticity in an age addicted to noise.

As twilight falls over Otukpo and the trees sway in evening rhythm, one imagines Bongos Ikwue still walking, still listening. The path may have changed, but the song continues. Somewhere between the rustle of leaves and the hum of memory, his melody lingers—proof that even a single walk, when guided by purpose, can echo for generations.

Closeout: Where the Wind Sings Back

In the final measure of his story, the forest becomes more than geography; it becomes metaphor. It stands for the inner space every artist must cross to find truth. Bongos Ikwue entered that space not to escape the world but to understand it. From those walks came songs that helped Nigerians interpret their own long journey through change and uncertainty.

The lesson endures: creation is not invention but discovery. When we listen long enough, the world composes itself through us. Bongos Ikwue’s walk through the forest was never about finding a song; it was about finding the silence that makes music possible. And in that sense, he is still walking—through memory, through melody, through the quiet that precedes every lasting sound.

Discussion about this post