It started with a tremor, not in the earth, but in the air — the kind that travels through the brittle silence of a country that has seen too much blood to flinch anymore. Somewhere in the cold, rocky plains of Plateau State, Reverend Dachomo’s voice broke through the static of a late-evening broadcast. It wasn’t a sermon. It wasn’t even a plea. It was a curse — old, deliberate, and sorrowful.

Those who heard it said it didn’t sound like anger. It sounded like mourning in motion — the kind of grief that had run out of tears and turned into fire. He spoke as a man who had buried too many of his own. His words carried the fatigue of entire communities reduced to statistics. And though his voice was carried on a small church radio network, within hours it spread — echoing through WhatsApp chains, Twitter threads, and Christian forums where believers argued over whether this was prophecy or blasphemy.

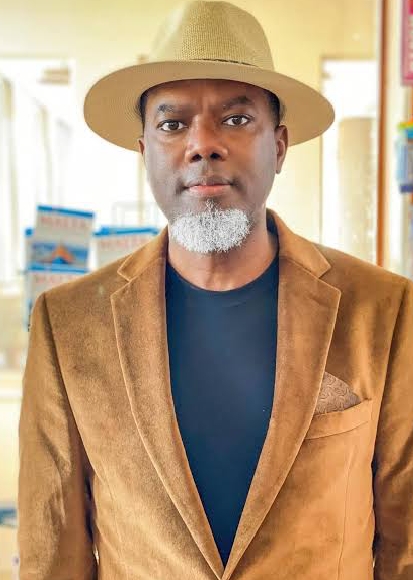

The Reverend had not mentioned politics directly, but everyone knew where his words were aimed. Reno Omokri — the fiery former presidential aide turned online activist, known for his intellect, his provocations, and his faith — had dismissed what many Christians across the Middle Belt and southern Nigeria called a genocide. He had questioned the use of the word “Christian persecution,” calling it an exaggeration, a manipulation of tragedy for political gain.

That skepticism met the raw wound of those who had watched villages burned and altars shattered. To them, denial was betrayal. And to Reverend Dachomo, it was something worse — an erasure of faith itself. The moment he cursed Reno Omokri, he was not speaking to a man on Twitter. He was speaking to a generation of Nigerian Christians who had grown numb to mourning.

The internet, hungry for spectacle, took it as another episode of religious theatrics. But beneath the viral exchanges was a question too painful to ignore — could a man of God curse another for denying suffering, or was this simply what happens when faith becomes the only courtroom left for justice?

As the Plateau winds howled that night, many said they could still hear his final words — not shouted, but whispered. A warning to anyone who mistook silence for peace.

The Blood on the Fields: A Country Haunted by Its Own Soil

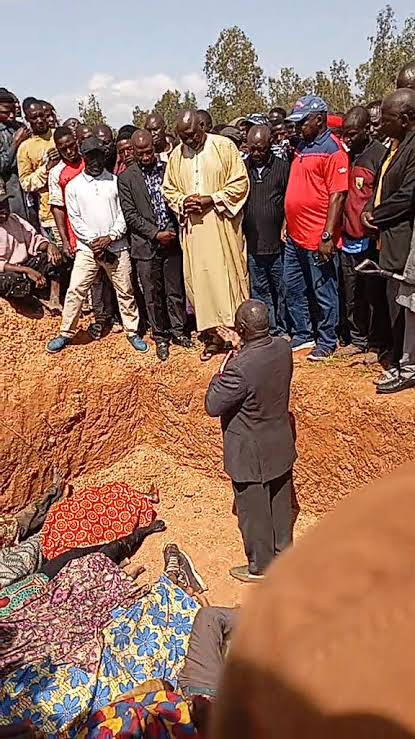

The next morning, when the sun stretched over the Jos Plateau, it illuminated what the world had long grown accustomed to ignoring — the soil still darkened by blood, the broken houses of Barkin Ladi, and the abandoned chapels that had once hosted Sunday choirs. The story of Christian bloodshed in Nigeria is not a single massacre. It is a slow, unending rain of violence — each drop a name erased, each silence a sermon on how easily lives are forgotten.

For over two decades, reports from the Middle Belt have documented a pattern too consistent to dismiss. Thousands of Christian farmers killed by armed herders, churches razed overnight, women taken from villages, and priests abducted on highways. Between 2015 and 2023 alone, global watchdogs like Open Doors International and the International Society for Civil Liberties and Rule of Law estimated over 45,000 Christians killed in Nigeria — more than in any other nation on earth during that period.

Yet somehow, the horror has never stayed long in the headlines. It has been muffled by politics, buried under ethnic complexities, or distorted by statistics. Each administration issued statements, and each mass burial ended with the same refrain — “we will bring the perpetrators to justice.” But justice, in Nigeria’s countryside, is a rumor that never arrives.

What made this particular moment explosive was that the killings were not being denied by outsiders — they were being questioned by one of their own. Reno Omokri, a man whose public image was intertwined with Christianity, had written that what many called a genocide was, in fact, a “rural conflict” between farmers and herders. He argued that religion was being used to inflame tribal divisions, and that Western media had manipulated the narrative to paint Nigeria as a land of Christian martyrs.

To those who had seen their churches turned to ashes, those words stung deeper than any bullet. For them, the graves were not theories. The faces were not statistics. Every denial felt like another killing — invisible this time, but just as real.

By the time Dachomo’s curse surfaced online, the national mood had already been drenched in grief. His curse was not merely about theology. It was about truth — about the right to name one’s suffering without being told it’s imaginary. In the silence that followed his outburst, the question that haunted Nigeria’s conscience returned like a ghost: how many must die before disbelief becomes cruelty?.

The Trump Ultimatum: A Threat That Stirred the Cross and the Crescent

When President Donald Trump announced, only days ago, that the United States might use military force against Nigeria over what he called the “genocide of Christians,” the world’s air seemed to tighten. It was not the first time an American leader had spoken on Nigerian insecurity — but it was the first time the threat carried the tone of divine warfare.

In Washington, cameras flashed as Trump stood behind the lectern, Bible resting beside his notes. “The killing of Christians in Nigeria must stop — or we will stop it ourselves,” he said, sending a shudder through Abuja’s corridors of power and the farmlands of Plateau. The statement, echoing across cable screens, was equal parts sermon and sword.

Within hours, Nigerian officials scrambled to contain the diplomatic fire. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs called the comments “regrettable.” Security spokesmen insisted that the violence in the Middle Belt was “complex and multifaceted,” not religious. Yet, for ordinary believers who had seen their churches reduced to ash, Trump’s words felt like vindication — a long-awaited acknowledgment from a global throne that heaven still noticed.

In the northern Christian belt, WhatsApp groups buzzed with prayers and prophecies. Some hailed Trump as “Cyrus II reborn,” the pagan king who once delivered Israel. Others warned that foreign intervention would drench the land with more blood. And in that tension — between deliverance and destruction — Nigeria found itself suspended.

Reno Omokri entered the storm at precisely the wrong moment. His social-media post disputing the idea of “Christian genocide” landed while emotions were at their rawest. To question the narrative, then, was to seem aligned with the killers. And in the echo chamber of faith and fear, reason rarely survives.

That was the soil from which Reverend Ezekiel Dachomo’s anger grew — the moment the pulpit and the tweet collided, and theology gave way to fire.

Reno Omokri’s Denial and the War of Faithful Words

Reno Omokri has never shied away from controversy. Born in Nigeria but shaped by years of global exposure, he has built a reputation as one of the nation’s most articulate defenders of former President Goodluck Jonathan and a vocal critic of northern political dominance. Yet within Christian circles, his stance on faith and politics has always been uneasy — too intellectual for the pulpit, too spiritual for the newsroom.

When he dismissed the claims of “Christian genocide,” he did not anticipate the emotional eruption it would trigger. To him, it was an act of logic — a correction of what he saw as propaganda used to divide the nation along religious lines. He cited data, referenced reports that emphasized farmer–herder clashes rather than religious cleansing, and accused Western commentators of exaggerating Nigeria’s crisis for missionary gain.

But words travel differently when they leave the mouth of a believer. For many, his argument sounded like betrayal dressed in sophistication. His followers split overnight — some applauding his rationality, others branding him a heretic in disguise. Screenshots of his posts circulated like digital pamphlets, each accompanied by photos of massacred villagers. “Tell them these are not Christians,” one caption read.

And somewhere on the Plateau, Reverend Dachomo was watching. To him, Reno’s denial wasn’t just an intellectual disagreement; it was desecration. How could a man who professed to serve Christ speak so lightly of those who died for His name? That question became the spark that turned sorrow into wrath.

Within days, Dachomo’s curse became legend — both feared and ridiculed. Some said he called on divine retribution, others said he merely spoke truth in the tongue of grief. But what mattered most was that the confrontation had stripped the nation bare: between the reason of the educated and the anguish of the wounded, whose truth would prevail?

When the Pulpit Became a Battlefield: Reverend Dachomo’s Outburst

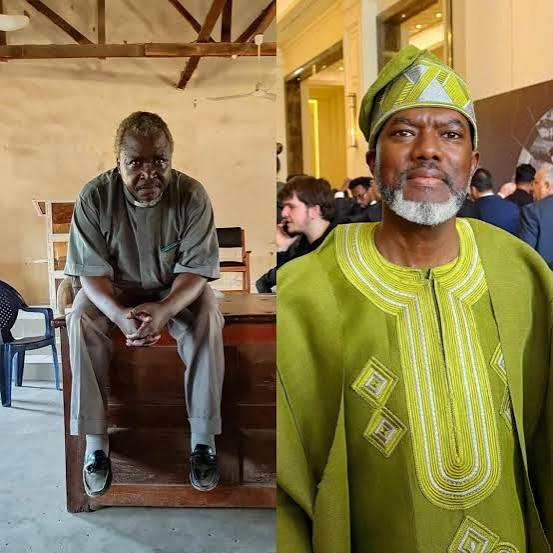

Reverend Dachomo was not the kind of man to seek attention. Before the controversy, he was known mostly in the northern Christian belt as a community pastor and teacher — a man of strong convictions but quiet temperament. Yet something had shifted after years of burying his own congregation. He had watched too many funerals, officiated too many services under open skies because the churches had no roofs left.

When Reno Omokri’s words reached him, they broke something that theology couldn’t mend. The Reverend didn’t curse out of rage; he cursed out of despair — a desperate cry that only heaven might hear. His words were raw, ancient, invoking justice from a God who, to many, had gone silent. “Let heaven judge between the truth and the tongue that mocks the truth,” he reportedly said.

Those words spread like wildfire, and in the days that followed, social media split into two camps. One saw a prophet defending the faith; the other saw a preacher lost in fanaticism. Yet, beyond the arguments, the emotional landscape of the story revealed something profound — Nigeria’s Christian identity was no longer united by suffering. It was being torn apart by how that suffering was narrated.

The pulpit had become a battlefield, and every statement was ammunition. Dachomo stood not only against Omokri but against the modern cynicism that sought to explain away faith’s pain with data and logic. To him, truth was not something that could be charted in statistics; it was something you carried in your scars.

And so the curse was not merely spoken — it was felt. Across the hills and valleys where believers still gathered in half-burned chapels, many whispered that the Reverend had only said what they all felt: that words denying pain are a greater sin than the acts that cause it.

When Faith Becomes Evidence: The Weight of Testimony

Truth, in every conflict, becomes the first casualty. But in Nigeria’s Christian North, truth doesn’t just die — it bleeds. Villagers can still point to where their churches once stood, where choirs once sang under cracked ceilings, where children once rehearsed hymns that now echo only in memory. For them, statistics mean nothing. They have graves for proof.

Across Jos South, Barkin Ladi, and Riyom, the soil is marked with crosses carved out of broken planks. It is here that testimonies live — not in reports, but in silence. To these communities, Reno Omokri’s insistence that “Christian genocide” was a myth sounded like a second killing, one committed with intellect rather than machete.

Reverend Dachomo’s curse, therefore, didn’t sprout from superstition; it was born from testimony. To curse is to call heaven to witness — to drag the divine into the courtroom of human suffering. For Dachomo, it was the only justice left. When institutions fail, language becomes rebellion. His words were not about vengeance but validation, an attempt to remind the world that pain, too, has a voice.

As the debate raged online, journalists and activists began tracing the stories of survivors — widows who buried their husbands with bare hands, boys who still carried the scent of gunpowder in their hair. Their testimonies spoke to a truth that transcended ideology: that something profoundly sacred had been violated, and denial was salt on the wound.

The pulpit had wept. The nation had scrolled past. And so, when Dachomo spoke, even his fury felt like prayer.

The Echo Chamber and the Empire of Tweets

Reno Omokri’s response came with the precision of a seasoned debater. He didn’t lash out — he lectured. His words were polished, global, and unyielding. “Facts,” he said, “must always defeat emotions.” But in Nigeria, where faith and emotion often share a body, facts rarely win hearts.

What followed was not dialogue but digital warfare. Hashtags turned into battlegrounds; believers and skeptics drew swords made of words. One camp defended Reno’s intellect, praising his courage to confront what they called “religious manipulation.” The other demanded repentance, declaring that no amount of education could wash away betrayal.

Truth, in that chaos, fragmented further. Reno’s defenders flooded social media with foreign reports, quoting think tanks that labeled Nigeria’s crisis as “ethno-economic.” But none of those reports could account for the names whispered at night — the pastors slaughtered mid-sermon, the families burned alive because of the cross on their doors.

And then came the viral video — Reverend Dachomo, eyes swollen with fury and faith, pronouncing his curse before his congregation. The clip spread like gospel wildfire, gathering millions of views. In its rawness lay a mirror of Nigeria itself: a people torn between forgiveness and fury, reason and revelation.

Reno Omokri tried to clarify. He said he believed in justice for the dead but rejected “Western narratives that reduce complex violence to religious persecution.” But by then, clarity was too late. The digital court had already ruled.

Trump’s Shadow Over the Cross

While Nigeria argued, Washington watched. President Trump, now deep into his renewed tenure, seized the chaos as proof of what he had warned about — a government unable to protect its believers. “Look at Nigeria,” he said during a rally in Texas. “Christians are dying, and their leaders deny it. We won’t stand by.”

His words turned the domestic argument into an international one. Cable networks replayed Dachomo’s curse alongside Trump’s threats, painting a portrait of a country collapsing under moral and spiritual weight. To Trump’s evangelical base, Nigeria became both prophecy and proof — a battlefield of good versus evil.

Inside Nigeria, the ripple was immediate. Religious leaders began calling emergency meetings, fearing U.S. sanctions or intervention. Muslim leaders condemned Trump’s rhetoric as “crusader politics.” The Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) cautiously welcomed his concern but warned that war would not resurrect the dead.

Meanwhile, Reno Omokri doubled down, accusing Trump of “weaponizing faith for foreign policy optics.” He wrote that the U.S. president’s sudden sympathy for Nigerian Christians was “a smokescreen for political gain.” But each word seemed to dig him deeper into the moral pit Reverend Dachomo had opened.

Trump had, intentionally or not, amplified the curse. What was once a local theological quarrel had now become a global moral theater — and the Reverend’s words, though spoken in grief, now echoed from Abuja to Washington.

Between the Altar and the Algorithm

Nigeria has always been a country where the pulpit holds more sway than parliament. Yet, in the digital age, sermons no longer end at the altar — they bleed into timelines and hashtags. What once took weeks to echo across villages now spreads in minutes through the glow of a phone screen.

Reno Omokri, perhaps unintentionally, became the first digital preacher of Nigeria’s modern faith wars. His words traveled faster than bullets — dissected, quoted, and remixed by voices that neither sought peace nor context. For every person who saw reason in his argument, another saw rebellion against the suffering church.

Reverend Dachomo’s response, equally viral, reminded the nation that spirituality is no longer confined to cathedrals; it now competes with algorithms. Faith has become a battlefield of pixels and prophecy, where the number of retweets sometimes determines the credibility of conviction.

In the weeks that followed, the debate stopped being about genocide and became a referendum on what Christianity itself had become — a religion of scholars or sufferers, of data or devotion. Between the altar and the algorithm, truth was still crucified.

The Curse and the Crown

There is something ancient about curses in African spirituality — not in the fetishized sense, but in their moral weight. They are not simply words; they are verdicts. They invoke accountability from powers unseen when human justice fails. Reverend Dachomo’s curse, spoken in public yet rooted in private anguish, carried that kind of weight.

As clips of the curse circulated, many began to interpret it beyond its literal sense. Some saw it as a symbol — a cry for moral awakening in a nation numbed by blood. Others claimed that the curse had political undertones, aimed at forcing leaders like Reno Omokri and President Tinubu to confront uncomfortable truths about faith-based persecution.

Meanwhile, conspiracy theories bloomed. Online preachers linked Trump’s sudden interest in Nigeria to Dachomo’s declaration, arguing that the Reverend’s words “opened a heavenly court” that stirred foreign powers. Political analysts dismissed this as superstition — but even they admitted that the timing was eerie.

Whatever one believed, the curse had become a crown — not of glory, but of responsibility. It reminded Nigeria that spiritual authority, when mixed with political grief, can shake nations.

The Burden of Denial

Denial in a wounded society is not just ignorance; it is survival. For some, refusing to call the killings “Christian genocide” is an attempt to prevent the nation from collapsing into sectarian war. For others, it is cowardice — the refusal to confront evil because it wears the mask of complexity.

Reno Omokri stands at that moral crossroads. To his critics, he represents the intellectual elite who analyze pain instead of feeling it. To his supporters, he is the rare voice of caution in a nation addicted to outrage. Both might be right — and both might be wrong.

But denial has consequences. It drains empathy from national discourse, making the dead just numbers and the survivors mere data points. It teaches a generation to debate instead of grieve. And when faith becomes argument rather than refuge, even prayer begins to sound political.

Reverend Dachomo’s curse, in that sense, was not just personal — it was prophetic. It exposed how far the church had drifted from the unity of its martyrs. The more Nigeria talked about who was right, the less it wept for those who were gone.

When the Nation Looked Away

Perhaps the most chilling part of the entire saga is not what was said, but what was ignored. As the world argued over Trump’s threat, Omokri’s defense, and Dachomo’s curse, the killings continued in quiet corners. Villages disappeared in the night, their names added to endless lists no one reads twice.

Television crews filmed statements, not funerals. Politicians condemned violence only when cameras were near. Even churches began to normalize tragedy — hosting thanksgiving services a week after burying their choirs. The crisis became routine, and routine kills faster than war.

For those who survived, it felt like living in a ghost country. Their pain was no longer breaking news; it had become background noise. And so when the Reverend’s voice broke through that silence, even those who disagreed with him understood why he screamed.

Nigeria had looked away too long. The curse was the sound of conscience demanding to be heard again.

Closeout: The Fire That Won’t Die

Weeks have passed since the curse, yet the embers still glow. In the marketplaces of Jos, in the churches of Kaduna, in the social feeds of diaspora believers, the argument continues to breathe. Did Reno Omokri commit heresy by denying Christian genocide, or was he only trying to save Nigeria from religious polarization?

No one can answer without choosing a side. And that is the tragedy. For a nation drenched in blood, truth has become partisan. Even pain now carries political affiliation.

Reverend Dachomo has since gone silent. Those close to him say he prays more than he speaks, as if waiting for heaven to render judgment. Reno, on the other hand, has resumed his broadcasts, quoting scripture to defend logic — a paradox that Nigeria knows too well.

Between them lies the ghost of thousands who never chose this debate — they simply wanted to live and worship in peace. Their silence, if it could speak, would likely ask for less theology and more humanity.

Discussion about this post