Nigeria’s attempt to stop buying imported petrol from the global market and instead run on locally refined product is one of the country’s most consequential economic bets.

At the center of that bet sits the Dangote Petroleum Refinery — a $20-plus billion project marketed as the machine that will end decades of costly petrol imports — and the Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC Ltd), the state oil company responsible for supplying crude and managing national fuel security. In 2024–2025 that contest spilled into court: Dangote sued regulators and fuel importers.

This article unpacks the full story: what Dangote alleged, how NNPC and regulators responded, how Nigerian courts treated the claims, what economic facts framed the litigation, and what the dispute signals for Nigeria’s energy transition — and for ordinary motorists paying at the pump.

The players and the prize

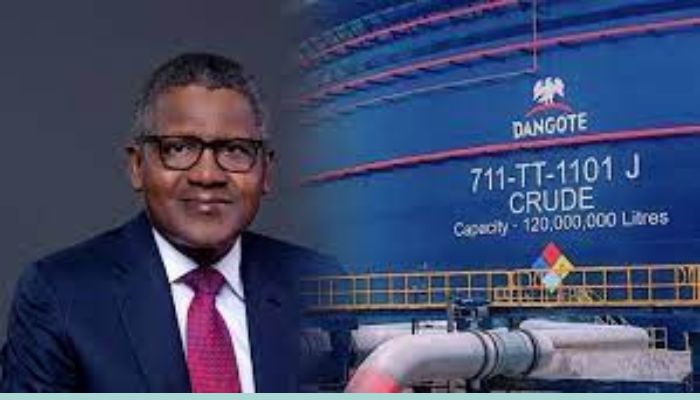

Dangote Petroleum Refinery — built by Aliko Dangote and his conglomerate, it began producing in 2024 and was designed to process up to 650,000 barrels per day. If run at scale it could satisfy most of Nigeria’s road-fuel demand and export refined products regionally.

The refinery’s promise is enormous: lower import bills, jobs, and a reversal of decades of foreign exchange drain caused by petrol imports. But getting there requires steady crude feed, stable forex access to buy crude (when local supply is insufficient), and an operating environment that allows the plant to place its product competitively in domestic markets.

NNPC Ltd (the state oil company) — holds the twin responsibilities of managing national crude flows and participating commercially. NNPC has been both supplier and competitor: it runs its own downstream operations and has historically issued import permits for marketers and the state that keep fuels flowing into the country when domestic refining (including private refineries) falls short.

NNPC’s stated posture has been that domestic refining capacity, even with Dangote online, does not immediately remove the need for imports given transitional supply, contractual obligations, and distribution realities.

NMDPRA (Regulator) — the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority issues import permits and regulates the downstream market. Dangote’s suit targeted permits the regulator issued to NNPC and several private marketers, arguing that their continued import licensing breached law and policy meant to prioritize domestic refining capacity. Regulators argued they were operating within the law and reacting to market realities.

Why the prize is big — curbing imports would shift billions of dollars in trade flows, reduce Nigeria’s chronic foreign exchange outflows for refined fuels, and materially raise Dangote Refinery’s domestic market share. For incumbents that profit from import and distribution, however, it would mean dislocation and lost margins. For the state, mis-steps could risk shortages during the transition. The stakes explain why both political and commercial pressure accompanied the legal filings.

The origins of the lawsuit — What Dangote argued

Dangote filed a suit in late 2024 (registered as FHC/ABJ/CS/1324/2024) seeking a court declaration that the regulator’s issuance of petrol import permits to the NNPC and other marketers was unlawful and should be set aside. The company argued that the permits frustrated the objective of domestic refining — in effect undermining the refinery’s economic viability and negating the government’s stated policy to stop petrol imports once refining capacity was available.

Dangote sought damages (reported around N100 billion / roughly $65–$66 million) and injunctive relief to halt certain import licences.

At the legal core was a contention about statutory interpretation: does the regulator have unfettered discretion to issue permits when a domestic refinery has the capacity to supply the market — or must it prioritize local refined product? Dangote said the regulator was not properly prioritizing domestic supply; regulators and NNPC said demand and transitional gaps justified continued imports.

This legal framing mixed administrative law (the regulator’s duty and statutory power) with economic policy (how to manage a shift from imports to domestic production).

Courtroom moves and early rulings

The case immediately attracted attention. NNPC filed procedural objections seeking to strike out or halt the case, arguing, among other things, that the claims were premature or misconceived given the complexity of fuel supply arrangements.

On March 18, 2025, a federal judge dismissed NNPC’s bid to halt the lawsuit — allowing Dangote’s substantive challenge to proceed. The ruling meant the court would consider the merits of whether import licences were lawfully granted and whether Dangote’s claimed injury was actionable.

While the litigation proceeded, the wider policy environment kept shifting. Dangote at times publicly signaled operating challenges: in March 2025 the refinery announced a temporary suspension of fuel sales in naira terms, citing mismatches between naira receipts and dollar-priced crude purchases — an episode that highlighted currency and cash-flow stresses even as the refinery scaled production. That commercial pressure framed the litigation: if the refinery could not secure crude volumes or a viable currency mechanism, its ability to displace imports would be impaired regardless of legal outcomes.

Court schedules, motions to amend, and procedural tussles followed through spring and early summer 2025 — a familiar pattern in high-stakes commercial litigation where litigation strategy sometimes mirrors commercial negotiation. At several points the suit looked like leverage: the mere filing and the specter of court orders that could restrain import licences put public attention and negotiating pressure on regulators and the NNPC.

The withdrawal: July 29, 2025 — what happened and why it matters

On July 29, 2025, Reuters and multiple Nigerian outlets reported that Dangote Refinery had withdrawn (formally discontinued) its lawsuit against the NMDPRA, NNPC Ltd and several marketers. The notice of discontinuance was filed in the Federal High Court in Abuja and the suit was formally marked as discontinued. Media reports — Reuters, Bloomberg, Premium Times, Punch, Africanews, BusinessDay — all documented the withdrawal, though the public filings and press coverage did not attach a detailed, single explanation for the discontinuance.

Why withdraw? Several overlapping reasons are visible:

• Commercial negotiation and behind-the-scenes deals. Lawsuits of this sort often function as bargaining chips. Withdrawal can mean Dangote and counterparties reached a commercial accommodation — renegotiated crude supply, import scheduling, or distribution arrangements — that made the court fight unnecessary. Multiple outlets suggested the courtroom pressure prompted talks between stakeholders.

• Timing and supply realities. Even with a world-class refinery online, real-time crude availability, distribution networks, and contractual obligations meant imports could not be instantly shut off without risking shortages. If regulators and NNPC convinced the refinery they would prioritize offtake or smooth the transition, the immediate need for injunctive relief lessened.

• Regulatory and political risk. Seeking court orders to halt import licences risks political backlash if shortages or price spikes follow. The state’s interest in orderly transition — and the political sensitivity of fuel availability — may have made a negotiated path preferable to headline-grabbing injunctions.

• Practical litigation calculus. High-value commercial litigation is expensive, unpredictable, and draws public scrutiny. The dismissal of some interlocutory bids in March showed courts would hear the case; but protracted litigation could delay practical solutions. Withdrawal can represent a strategic pause rather than absolute concession.

The discontinuance did not amount to an admission of defeat in public statements; neither did it deliver a definitive judicial ruling clarifying the regulator’s obligations. Instead, it left the deeper statutory and policy questions unresolved in the courts while the market continued to adapt.

The wider economic realities that shaped the dispute

Legal arguments alone cannot explain the saga. Three structural realities shaped behavior and constrained legal remedies.

A. Crude supply and refinery feed constraints. Dangote’s refinery is large — arguably large enough to supply Nigeria’s domestic petrol needs — but the plant still requires steady crude feed. Nigeria’s own crude production has been volatile; securing additional crude (including from international sources) has been part of Dangote’s strategy. The refinery obtained crude from the U.S., Brazil, Libya and Angola at times, but scaling to full, steady throughput requires complex, expensive logistics and dollars. The Financial Times and other outlets traced Dangote’s global sourcing and financing efforts.

B. Forex and currency mismatch. A recurring friction was currency. Dangote buys crude in dollars but historically sold local fuel priced in naira to the domestic market. When naira receipts do not cover dollar obligations — or when access to foreign exchange is constrained — refineries face cash-flow and pricing dilemmas. Dangote briefly suspended sales in naira in March 2025 to underscore this mismatch. Currency mechanics create economic incentives that neither courts nor regulators can instantly fix.

C. The structure of Nigeria’s downstream market. For decades Nigeria’s downstream sector relied on imports, middlemen, and a network of marketers with established supply chains. An abrupt legal cut-off of import licences would disrupt supply chains, potentially causing shortages and price spikes. Regulators must balance the policy goal of import substitution against immediate fuel security. That balancing act explains their reluctance to simply cancel permits overnight.

These realities show why a purely legal remedy — a court order nullifying import licences — is only one lever among many. Commercial negotiation, supply contracting, forex policy, and regulatory sequencing matter greatly to outcomes on the ground. The litigation illuminated those dependencies even as it sought to change them.

Political economy: Why powerful interests resisted a rapid phase-out of imports

Multiple actors had incentives to slow or shape the transition.

NNPC and state interests. NNPC, as a supplier and distributor with strategic responsibilities, had to ensure continuity of supply and might prefer a staged transition where it manages the sequencing to avoid shortages. It also retains commercial interests that could be affected by a rapid shift. Courts are sensitive to broad public interest consequences — which favors caution.

Importers and marketers. Private importers and marketers who built networks around importing refined products face commercial displacement if imports were curtailed. They wield political clout through employment, regional distribution, and relationships across the sector. Abrupt legal orders that upend their businesses risk fierce opposition.

Regulatory caution and institutional inertia. Regulators, who must calibrate licensing decisions against market evidence and international obligations, typically prefer policy instruments (schedules, quotas, transition plans) over blunt court orders. They also must withstand lobbying and manage the optics of fuel availability.

Currency and macro management. The Central Bank and fiscal authorities are sensitive to the macroeconomic implications of any policy that affects forex demand or public revenue. A disorderly switch could increase pressure on the naira or worsen prices. These macro stakes shape the political environment in which disputes like Dangote’s play out.

The combination of vested commercial interests, state responsibilities, and macro instability helps explain why the regulator and NNPC pushed back in court and in public statements, and why the dispute ended up being at least partly negotiated rather than resolved definitively by a judge.

Legal and policy consequences of the withdrawal

The discontinuance leaves three important consequences.

No judicial precedent, but a practical truce. Because the case was discontinued rather than decided on its merits, the courts did not authoritatively interpret the regulator’s duty to prioritize domestic refining over import licensing. That unresolved legal question remains a potential flashpoint for future disputes. At the same time, withdrawal suggests practical agreements may have been reached, creating a de-facto policy path without a formal precedent.

A window for negotiated transition frameworks. The episode underlined the need for clear, enforceable transition mechanisms: scheduled phase-downs of permits, guaranteed offtake arrangements, currency hedges or FX guarantees for crude purchases, and transparent arbitration mechanisms. Policymakers and industry players now face pressure to codify such frameworks to avoid repeat litigation.

Political signaling to investors and markets. For investors, the litigation and its withdrawal offer mixed signals. On one hand, the fact that a major investor resorted to courts underscores unresolved policy frictions; on the other, the swift move to discontinue the suit — likely after negotiation — shows that commercial solutions remain possible. Long-term investor confidence will hinge on predictable supply contracts and clearer public policy.

Scenarios going forward — three plausible pathways

Scenario A — Managed transition (most likely near term). Regulators, NNPC, and Dangote (and other refiners) agree a staged transition: import permits are gradually reduced with clear timelines; NNPC or other suppliers commit crude offtake; FX mechanisms are put in place to support crude purchases. This minimizes disruption and avoids future court fights — but the devil is in contractual detail and enforcement. Evidence from the discontinuance suggests parties preferred negotiation, making this pathway plausible.

Scenario B — Regulatory reform and clearer statutory rules. Policymakers enact clearer regulatory standards that require prioritization of domestic refining when capacity is available, with transitional safeguards to prevent shortages. This would reduce discretionary conflicts but requires political will and credible enforcement. The unresolved legal question from the discontinued suit would then be addressed by statute rather than court.

Scenario C — Reversion to status quo with repeated flareups. If underlying frictions — crude supply, forex mismatch, entrenched import networks — remain unresolved, the system could revert to periodic legal or political clashes. Parties may file new suits or use other levers. That outcome would maintain uncertainty and likely deter some investment. The March 2025 filings and the later discontinuance show how easily the dispute could reignite if negotiations breakdown.

What this dispute teaches about industrial policy in oil economies

Three broad lessons emerge that apply beyond Nigeria.

1. Industrial capacity is necessary but not sufficient. Building a world-scale refinery solves one piece of the problem. The rest — feedstock security, forex arrangements, distribution logistics, and policy sequencing — must be solved to realize the promised benefits. Physical capacity without predictable commercial frameworks yields underutilization and friction.

2. Law is a tool, not a panacea. Courts can enforce rules and check regulatory excess, but they cannot conjure crude, dollars, or distribution networks. Litigation can be a lever for negotiation; its practical effect often lies in the leverage it creates rather than a final judgment. The Dangote discontinuance illustrates this dynamic.

3. Transitions require sequencing and safety valves. Shutting down imports overnight is risky. Thoughtful sequencing — including temporary import quotas, FX guarantees for refineries, and clear timelines — reduces instability and the temptation to litigate. Policymakers should design transitions that protect consumers and investors simultaneously.

Closing note — beyond headlines

The headline that Dangote “lost” or “won” this suit would miss the point. The real story is less courtroom drama and more institutional engineering: Nigeria has finally built refining capacity capable of meaningfully reducing import dependence, but the path from capacity to national fuel independence runs through contracts, currency markets, regulators’ decision rules, and politics. The July 2025 discontinuance of Dangote’s suit closes one chapter without settling the larger policy books.

If policymakers, NNPC, private refiners, and marketers can translate the episode’s lessons into credible transition mechanisms, Nigeria could achieve the economic gains promised by the refinery — cheaper imports, more jobs, and regional export competitiveness. If they cannot, legal skirmishes will recur and the refinery’s promise will be harder to capture.

Discussion about this post