On that day, the silence inside Abuja was not just about its still-growing skeleton of glass and concrete. It was about anticipation. A man was arriving — not just any man, but one whose face had already transcended biography and become symbol. To see him was to see the story of Africa’s long 20th century struggle condensed into a single figure.

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, the prisoner who had walked free after twenty-seven years of confinement, the reconciler who had turned bitterness into a weapon sharper than vengeance, was stepping onto Nigerian soil.

Abuja had hosted presidents, generals, and foreign dignitaries before, but this was different. Mandela was not merely another head of state. He was the embodiment of a moral debt — a reminder of Nigeria’s sacrifices during the apartheid struggle and, at the same time, an uncomfortable mirror reflecting the contradictions of a country that had poured resources into liberating South Africa while suffocating its own people at home.

The irony was almost unbearable: here was Mandela, the global prophet of freedom, standing in a capital city controlled by General Sani Abacha, one of Africa’s most repressive dictators. Abuja became the stage for a rare kind of confrontation — not of armies or weapons, but of histories colliding.

Abuja in the 1990s: A Capital of Contradictions

Unlike Lagos, with its salty Atlantic breeze, unruly traffic, and ceaseless noise, Abuja was deliberately engineered to be sterile, orderly, and removed from the nation’s contradictions. The decision to build it dated back to the 1970s, when planners sought a neutral ground, away from the overcrowded coastal hub, where Nigeria’s ethnic and political rivalries might dissolve in the fresh air of the interior.

By the mid-1990s, Abuja had been officially designated as the capital, but it remained a city half-born. Its wide expressways cut through patches of forest and rock. The Aso Rock monolith, rising like a sentinel, loomed over the presidential villa. The skyline of ministries — neat, modernist blocks of concrete and glass — stood almost too clean, like props waiting for a script. Behind the façade of order, however, Abuja bore the tension of a Nigeria at war with itself.

General Sani Abacha ruled from within this landscape. His regime was one of the most repressive Nigeria had ever known. Political opponents disappeared. Journalists were silenced. Oil revenues were hoarded and squandered with impunity. The promise of the June 12, 1993 election — Nigeria’s fairest, annulled before it could birth a civilian government — still hung in the air like a wound that refused to heal. For ordinary Nigerians, Abuja symbolized not just a new capital, but also the distance between rulers and ruled. The generals governed behind guarded walls while the people faced poverty, uncertainty, and fear.

And yet, Abuja was also the seat of Nigeria’s grandest aspirations. It was here that foreign dignitaries were received, where summits were staged, and where Nigeria projected itself as Africa’s giant. It was in this paradoxical space — a city half dream, half deception — that Nelson Mandela would make his symbolic appearance.

Mandela’s arrival in Abuja was not simply a diplomatic courtesy. It was a reckoning: a return to the country that had spent billions of naira, sacrificed international prestige, and carried the weight of sanctions and oil boycotts in the name of South Africa’s freedom. Nigeria had played a central role in the global anti-apartheid movement. Its diplomats had been relentless at the United Nations. Its students had marched in solidarity, often brutalized by their own police for protesting in another country’s name. Its oil embargoes had cost billions in lost revenue.

But by the time Mandela came to Abuja, Nigeria itself was shackled. The paradox could not be ignored. A country that had given so much to free Mandela’s South Africa was now captive to its own homegrown authoritarianism. Abuja embodied that contradiction: a city built to symbolize renewal, yet ruled by repression.

For Nigerians watching Mandela’s visit unfold, the symbolism was almost unbearable. Here was the man they had cheered for decades, the man for whom their fathers and mothers had sacrificed, arriving in their gleaming new capital — only for them to receive him under the shadow of a regime that represented the very opposite of everything he stood for.

Abuja in the 1990s was not just a city. It was a metaphor. It was the architectural mask of a nation that wanted to appear stable while rotting beneath. It was a stage where hope and despair shared the same spotlight. And into this fragile theatre walked Nelson Mandela, carrying with him both gratitude and judgment, both memory and prophecy.

Mandela Before Abuja: A Long Walk to Leadership

By the mid-1990s, Nelson Mandela was no longer merely a South African figure; he was a global archetype. His biography had become myth, his name shorthand for sacrifice, resilience, and the improbable triumph of forgiveness over vengeance.

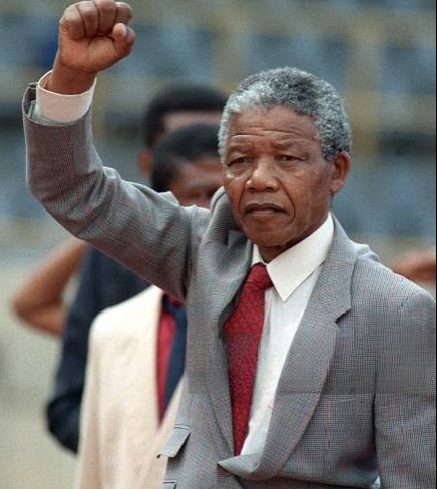

When he walked free from Victor Verster Prison on 11 February 1990, the world had already cast him as the saint of the 20th century. The image of Mandela, tall and unbowed, fist raised in triumph as he strode into the sunlight, was broadcast across continents. It wasn’t just South Africa that exhaled; it was the entire globe, especially Africa, which had long carried the psychic burden of apartheid as a wound on its collective dignity.

For Mandela, freedom was not the end of struggle but the beginning of a more delicate war — the negotiation of South Africa’s transition from racial dictatorship to democracy. His years in prison had stripped him of youth but sharpened his political clarity. He understood that the world wanted him to embody reconciliation, but reconciliation itself was fragile, built on compromises that could fracture under the slightest pressure.

By 1994, Mandela had become South Africa’s first black president, elected in a landslide that felt less like politics than destiny. His inauguration was watched live across Nigeria, where families huddled around flickering television sets powered by shaky generators. Nigerians who had lived through military coups, annulled elections, and shattered promises felt a surge of pride that an African nation had managed to pull off what seemed impossible.

Yet Mandela’s presidency carried a weight beyond South Africa’s borders. He was expected to be Africa’s statesman, the moral compass of a continent riddled with dictatorships, civil wars, and economic despair. He could not confine himself to Pretoria; the world insisted on his voice. And so, when he came to Abuja, he was not simply another African leader attending a summit or exchanging handshakes. He was the conscience of Africa walking into a house divided against itself.

Mandela knew the power of symbols, perhaps better than any leader of his generation. His own life was a series of symbolic confrontations: refusing to bow in court, choosing prison over exile, emerging from Robben Island unbroken. He understood that his presence in Nigeria would not be read as mere diplomacy. It would be seen as a mirror. Nigerians would interpret his words not only as gratitude for past sacrifices but also as commentary on their present suffering.

This was the burden Mandela carried into Abuja — the paradox of being both guest and judge, both brother-in-struggle and outsider-with-authority. He had to thank Nigeria for its decades of support while somehow navigating the uncomfortable truth: that the same Nigeria which had stood tall against apartheid was now bent under the weight of its own chains.

The Nigerian Connection: Oil, Sanctions, and Struggle

Nigeria’s relationship with Mandela and the South African liberation movement was not incidental. It was foundational. Few countries on earth had invested more political, economic, and emotional capital into the fight against apartheid.

As early as the 1960s, Nigeria had declared apartheid South Africa a pariah state, cutting off diplomatic ties and mobilizing African solidarity. Successive Nigerian governments, both civilian and military, poured resources into the cause. In 1976, Nigeria established the Southern African Relief Fund (SARF), where civil servants, students, and even schoolchildren were encouraged — sometimes compelled — to contribute a portion of their wages and allowances to support liberation movements. Millions of dollars were funneled to the African National Congress (ANC), the Pan Africanist Congress, and other groups fighting apartheid.

Oil became Nigeria’s weapon. In the late 1970s and 1980s, Nigeria led global campaigns to embargo South Africa, refusing to sell crude oil to a regime that thrived on energy imports. The decision cost billions in lost revenue, but it elevated Nigeria’s standing as Africa’s frontline state in the anti-apartheid war. Nigerian diplomats were tireless at the United Nations, pushing for sanctions, mobilizing votes, and pressing Western nations to isolate Pretoria.

For ordinary Nigerians, the struggle was personal. University campuses turned into hotbeds of anti-apartheid activism. Students protested outside embassies, held sit-ins, and raised funds. Nigerian musicians sang songs of solidarity. Newspapers carried regular reports on Mandela’s imprisonment, turning his cell number — 46664 — into a symbol etched into public consciousness.

By the 1980s, Nigeria was so invested in the cause that South African exiles often referred to Lagos as their second home. ANC members found safe haven in Nigeria, living, training, and strategizing under the protection of successive governments.

But this solidarity was not without irony. While Nigeria postured as Africa’s liberator abroad, it often crushed dissent at home. Student activists who protested against apartheid were sometimes met with the batons of Nigerian police. The country that funded Mandela’s freedom was also the country where writers like Wole Soyinka and Ken Saro-Wiwa were hounded, where journalists were jailed, and where citizens lived under the suffocating grip of military decrees.

This contradiction — external heroism, internal repression — was the stage Mandela was walking into. Nigeria wanted recognition for its role in South Africa’s liberation, but it also risked being judged for betraying its own democratic aspirations.

Mandela knew this. He was too astute a statesman not to see the paradox. Nigeria had given generously to his struggle, but it was now demanding a moral account it had not settled at home. Abuja, the city of dreams built on a plateau of contradictions, would be the site where this tension crystallized.

The Arrival In Abuja

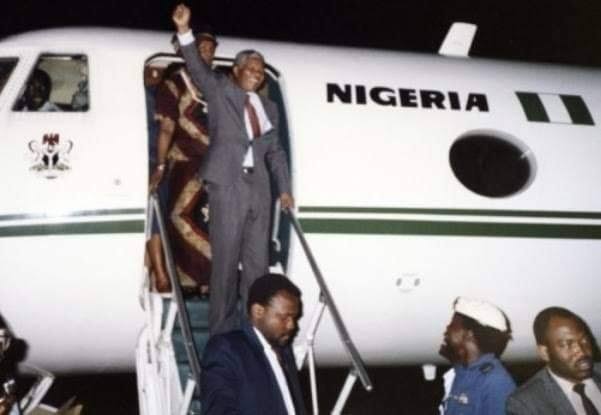

Nelson Mandela’s plane descended over Abuja with the precision of ritual. Below, the city stretched out like a deliberate design: broad highways radiating from the center, government buildings aligned in geometric symmetry, the Aso Rock monolith anchoring the landscape like a silent judge. It was meant to look permanent, inevitable — the architecture of control.

At Nnamdi Azikiwe International Airport, soldiers stood rigid in formation. The air carried both ceremony and unease. Military bands rehearsed their notes, the Nigerian flag fluttered in the hot breeze, and protocol officers adjusted their ties nervously. For the generals in power, Mandela’s visit was both opportunity and threat: a chance to bask in the glow of Africa’s most admired statesman, but also a moment of vulnerability. His presence reminded the world that Nigeria, once respected as Africa’s defender of freedom, was now ruled by one of its most repressive regimes.

Mandela emerged from the aircraft with the slow dignity that had become his signature. Every gesture, every step seemed deliberate, as though he understood the theatre of history and knew he was performing for posterity. Cameras flashed. Nigerian dignitaries surged forward. And behind the handshakes and rehearsed smiles, the tension was unmistakable.

Ordinary Nigerians watched from afar, their eyes glued to evening news broadcasts, radios humming in crowded buses, and newspaper stands where black-and-white photographs captured the moment. For many, seeing Mandela on Nigerian soil was not just an international affair — it was personal. He was the man for whom their parents had marched, for whom their nation had sacrificed oil revenues, for whom slogans had been painted on university walls.

Yet the paradox was stark: here he was, the global face of freedom, being welcomed by men whose very grip on power was defined by silencing freedom at home. General Sani Abacha, Nigeria’s ruler, embodied that contradiction. Stocky, unsmiling, his dark glasses hiding expression, Abacha carried the aura of menace even in moments of pomp. When he extended his hand to Mandela, it was more than protocol. It was history colliding — freedom meeting tyranny, moral authority shaking hands with brute force.

For those present, the choreography of the handshake carried layers of meaning. To the regime, it projected legitimacy: Mandela had come to Abuja, and that meant Nigeria still mattered. To the people, it was a bitter irony: the man they admired most was standing beside the man they feared most.

Mandela, ever conscious of symbols, did not flinch. He smiled, embraced the role, and carried himself with the grace of someone who had walked through darker corridors than this. Yet those who studied his speeches and gestures that day knew there was more than gratitude in his visit. There was an undercurrent of judgment — not in open rebuke, but in the way he reminded Nigeria of its better self.

Mandela and Abacha: The Unheeded Requests

The private meeting between Mandela and Abacha has never been fully documented, but its outlines are known. Mandela was too disciplined to storm publicly against a host, but he was also too committed to freedom to stay silent in private.

Nelson Mandela’s key requests to Sani Abacha during his 1994 visit to Abuja were to release political prisoners, specifically:

1. Chief Moshood Kashimawo Olawale (M.K.O.) Abiola – the presumed winner of Nigeria’s annulled 1993 presidential election. Mandela urged Abacha to allow Abiola his freedom and political participation.

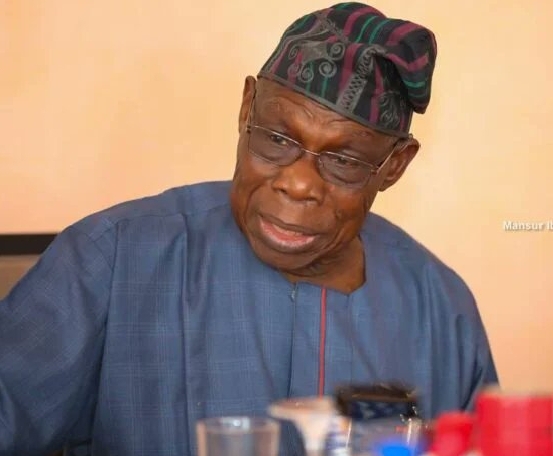

2. General Olusegun Obasanjo – former military head of state, who had been imprisoned by Abacha’s regime under house arrest or detention conditions. Mandela sought clemency and humane treatment.

For Mandela, it was a matter of principle. He had seen what repression could do to a people, and he carried the scars of decades spent in confinement. For Abacha, it was a matter of power. Nigeria’s strongman was not about to let an outsider dictate the tempo of his rule, not even an icon like Mandela.

The contrast could not have been sharper. Mandela represented the triumph of collective sacrifice and moral persuasion. Abacha represented the cold calculation of military force. Mandela’s authority came from suffering and survival; Abacha’s from fear and decree.

It was as if two Africas stood face to face in that meeting room: one Africa struggling toward light, another sinking deeper into shadow. For Nigerians, the knowledge that Mandela had dared to press their dictator — even behind closed doors — was itself a balm. It meant their plight had been heard by someone who mattered, someone who carried Africa’s moral weight into every room he entered.

The clash, however, was not merely personal. It was historical. Nigeria and South Africa had long mirrored each other in paradoxical ways: both rich in resources, both giants of their regions, both carrying the weight of colonial wounds. But while South Africa had emerged from the long night of apartheid into a fragile but real democracy, Nigeria remained chained to its cycle of coups and dictatorships. Mandela’s presence in Abuja forced Nigerians to confront this contrast.

Mandela’s Repprted Speech in Abuja: Echoes of Sacrifice

When Mandela finally addressed Nigeria in public, the weight of his words was unmistakable. He thanked Nigerians for their decades of support — the oil embargoes, the diplomatic battles, the student protests, the financial sacrifices. He reminded them that South Africa’s freedom had not been won by South Africans alone but by a coalition of peoples who believed apartheid was an affront to human dignity.

His words carried gratitude, but also an implicit challenge. Gratitude, because Nigeria had indeed carried the anti-apartheid struggle on its shoulders. Challenge, because a nation capable of such sacrifice abroad could not excuse repression at home.

For those listening, the speech carried double meaning. On the surface, it was celebration — a thank you, an acknowledgment of solidarity. Beneath the surface, it was an unspoken indictment — a reminder that Nigeria, too, deserved the freedom it had fought to give others.

Students, activists, and ordinary citizens clung to those words like oxygen. They heard in Mandela’s voice the echo of their own demands for democracy, even if he did not spell them out. They knew that in the coded language of diplomacy, Mandela was urging Nigeria to live up to its own sacrifices.

Abacha’s circle, on the other hand, heard something else. They heard the careful diplomacy of a man who refused to directly embarrass his host, but who could not resist pointing toward a higher moral ground. To them, Mandela’s speech was tolerable so long as it did not ignite open rebellion.

But the truth was, it already had. Not in the form of protests that day, but in the slow-burning embers of memory. Nigerians who lived through those years still recall Mandela’s Abuja visit not as a simple ceremony but as a reckoning. It was a moment when the moral mirror was held up, when the contradiction of Nigeria’s identity — liberator abroad, captive at home — was laid bare.

The Long Shadow of Abuja

Mandela’s Abuja moment did not end with the ceremonies, speeches, and handshakes. Its shadow stretched across the years that followed, as Nigeria staggered toward the end of Abacha’s reign.

Abacha himself seemed unmoved by Mandela’s quiet admonitions. He continued to rule with iron control, silencing critics, hoarding oil wealth, and isolating Nigeria on the global stage. But outside the fortified walls of Aso Rock, Mandela’s visit lingered in the memory of activists and ordinary citizens. It became part of the moral arsenal they drew upon in their fight for democracy.

When Abacha’s regime executed Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight other Ogoni activists in November 1995, the world’s outrage was amplified by the contrast with Mandela’s South Africa. The hangings shocked global conscience — and for many Nigerians, Mandela’s earlier presence in Abuja took on prophetic weight. It was as if his visit had foreshadowed the extremes of Nigeria’s contradictions: the liberator welcomed in pomp, the dissidents executed in darkness.

Abacha’s sudden death in June 1998 shifted the nation’s trajectory. It was an ending so abrupt and mysterious that it seemed like the hand of fate itself had intervened. In the vacuum that followed, Nigeria began its slow crawl back toward democracy. By 1999, the military had handed over power to an elected civilian government under Olusegun Obasanjo.

Mandela, nearing the end of his own presidency in South Africa, watched Nigeria’s return to democracy with cautious optimism. For him, Abuja would always be remembered not just as a diplomatic stop but as a moment when Africa’s two giants confronted each other’s shadows. South Africa had emerged from the dark night of apartheid; Nigeria was only beginning to escape its own long twilight of military dictatorship.

The Abuja encounter remained symbolic — a hinge between Nigeria’s past sacrifices and its future struggles. For Nigerians, it reinforced the idea that their destiny was tied not just to the might of their oil wealth or the size of their population, but to the moral choices they made about governance and freedom. Mandela had reminded them, however subtly, that true greatness lay not in foreign policy heroics but in domestic justice.

Mandela’s Legacy in Nigeria’s Memory

Today, decades after Mandela’s Abuja visit, the memory lingers with an almost mythic aura. Nigerians still recall the pride of seeing him on their soil, the gratitude in his voice, and the dignity in his bearing. His presence was validation — proof that their sacrifices in the anti-apartheid struggle had not been forgotten.

But alongside the pride is the haunting sense of what could have been. For many, Mandela’s visit has become a parable: Nigeria, the giant that freed others but could not free itself, standing face to face with the man who embodied liberation. Abuja, the city meant to symbolize national unity, became instead the stage for a moral reckoning.

In popular memory, Mandela is often contrasted with Nigeria’s own leaders. His humility against their arrogance. His sacrifice against their greed. His capacity for forgiveness against their addiction to vengeance. This contrast has shaped how generations of Nigerians judge their rulers — always against the Mandela standard, always against the day when he came to Abuja and showed what leadership could look like.

Cultural memory has preserved the symbolism in unexpected ways. Writers, poets, and musicians have evoked the moment, often casting Abuja as the theatre where Nigeria was forced to confront its contradictions. For younger Nigerians who did not witness the visit directly, the story is retold as legend — a moment when Africa’s greatest moral voice came to remind Nigeria of the weight of its own history.

Closing Reflection: The Requests That Went Unheeded

As Mandela stepped away from Abacha’s Abuja, the room’s heavy air lingered in his mind. The requests he had carried — appeals for justice, clemency, and the safeguarding of democracy — had not found purchase. Abacha’s silence, firm and unyielding, was a reminder that even the world’s most moral leaders could meet walls of power impervious to conscience.

Yet, the encounter was not futile. Mandela’s presence, his words, and the very act of asking held symbolic weight far beyond the room’s walls. He illuminated the gap between expectation and action, between principle and authority. Nigerians, Africans, and the global community witnessed a moral confrontation in which the righteous voice met the cold force of dictatorship.

In the end, the requests went unheeded, but Mandela’s legacy endured — a testament to persistence, to the courage of speaking truth even when silence answers, and to the idea that moral authority can shine even when political power resists. Inside Abuja, Mandela had met Abacha, and though the pleas were denied, the world had seen a confrontation that would echo through history.

Discussion about this post