The morning had begun like any other at Faith Tabernacle. The sprawling grounds of Canaanland in Ota were alive with the usual rhythm—hymns rising like waves, the vast congregation swaying in unison, voices stitched together in worship. Then, a pause. A silence heavy enough to still the restless hum of thousands. From the altar, the preacher’s voice sliced through the air, not with comfort or blessing, but with a question that seemed almost impossible in its audacity:

“Is there any witch here? Stand up.”

It was a moment that made time feel suspended. Some say the air turned colder. Others remember eyes darting nervously, as if the question itself carried an unseen weight. The congregation, thousands strong, sat frozen—unsure whether to laugh, to shiver, or to pray harder. And yet, in the haze of disbelief, something happened that would ripple across Nigeria’s Pentecostal memory.

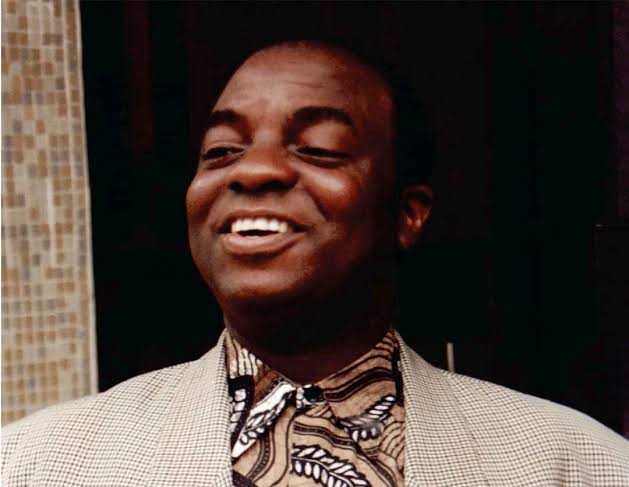

This is not just the story of a declaration at Ota. It is the story of how a single moment—whether literal, symbolic, or both—became part of Nigeria’s spiritual folklore. It is a story about fear and faith, about cultural battles with the unseen, about how a nation where witchcraft and Pentecostalism collide interprets its own mysteries. It is also a story about the man at the center of it all: Bishop David Oyedepo, the founder of Living Faith Church Worldwide, whose words that day became a reference point for both his critics and his believers.

What happened next is still argued over. Some call it myth, others swear it is testimony. But all agree on one thing: the question marked a turning point.

The Making of a Preacher of Audacity

David Oyedepo’s journey did not begin in Ota. It began in 1954 in Osogbo, in present-day Osun State, where he was born into a family that carried both Islamic and Christian roots. His grandmother, a devout Anglican, became a formative influence, drawing the boy into the rhythms of church life. Yet the true pivot came in 1969, when at the age of 15, he had a personal conversion experience.

By 1981, during an eighteen-hour vision in Ilesa, Oyedepo received what he would later describe as his life’s mandate: “the liberation of the world from all oppressions of the devil.” It was a commissioning that would shape every sermon, every building project, and every symbolic battle he would ever fight.

The phrase “oppression of the devil” was no mere theological metaphor in Nigeria. It tapped directly into the lived fears of millions. In Yoruba, Igbo, and other Nigerian cosmologies, witchcraft was more than superstition—it was a perceived reality that explained sickness, misfortune, and death. By the late 1970s and early 1980s, Pentecostal Christianity in Nigeria had begun to position itself as the antidote: a spiritual warfare faith that promised protection and power over witches, demons, and unseen forces.

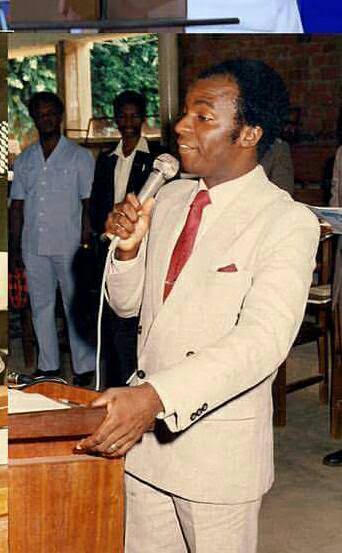

For Oyedepo, the call was not to build a quiet church of piety, but a loud, uncompromising one that would stare fear in the face. And so, his ministry grew rapidly—first in Kaduna, then Lagos, and ultimately in Ota, where the Faith Tabernacle would become the headquarters.

Ota, Land of Shadows and Sanctuary

Ota was not chosen at random. The land, once known for thick forests and small settlements, carried stories of spiritual strongholds. Local folklore brimmed with accounts of strange occurrences, night marauders, and whispered tales of covens. To build a megachurch there was not just an architectural feat—it was a symbolic reclamation of space.

When construction of Faith Tabernacle began in 1998, it was with the bold claim that it would house the largest church auditorium in the world. In less than twelve months, the structure stood complete: a 50,400-seat sanctuary with overflow capacity pushing into the hundreds of thousands.

To believers, this was proof that God’s hand was with Oyedepo. To critics, it was megalomania cloaked in religion. But for the worshippers who filled the pews week after week, it was holy ground. And on this ground, one day, the challenge to witches would be issued.

The Altar Call That Shook the Room

Accounts of the actual moment vary. Some place it as far back as 1979, in a smaller setting, when a young Oyedepo first tested the boundaries of his boldness. Many others claim it happened publicly at Ota, during the explosive early years of Faith Tabernacle.

In one sermon clip circulated on YouTube, Oyedepo himself recalls: “Few years ago, I made an altar call: If there is any witch here, stand up.”

Nairaland forum discussions echo the story, with posters claiming that some individuals actually stood up and admitted to practicing witchcraft, even narrating dark details of how they “suck blood.”

Regardless of where or how exactly it unfolded, the event entered Pentecostal memory as “the day Bishop Oyedepo declared war on witches.” It was more than a sermon—it was a confrontation staged in the open, a daring act in a culture where witches were feared but rarely challenged so directly.

Fear, Faith, and Folklore Collide

To understand why this moment mattered, one must grasp Nigeria’s entanglement with witchcraft. From the delta creeks to the Yoruba hinterlands, the idea of witches as malevolent beings capable of harm is deeply rooted. Colonial records brim with accounts of witchcraft trials and accusations. Anthropologists describe communities where misfortune was often attributed to spiritual attack.

In this context, Oyedepo’s declaration was seismic. It was not merely rhetorical—it challenged a centuries-old silence. To demand that witches reveal themselves was to strip fear of its secrecy, to drag shadows into light.

For believers in the congregation, it was electrifying. If their pastor could confront witches without flinching, then surely their own battles—sickness, poverty, barrenness—could be won. For skeptics, it was theater, a manipulative play on superstition. But either way, it was unforgettable.

The Aftermath Inside and Outside the Church

Inside the Church:

The altar call reinforced Oyedepo’s reputation as a fearless general in God’s army. Testimonies swelled. Faith deepened. Living Faith Church grew exponentially—first within Nigeria, then across Africa, then worldwide. Today, it boasts branches in over 65 nations.

Outside the Church:

The story fueled debates about Pentecostalism in Nigeria. Was it empowering people against unseen fears, or exploiting cultural anxieties? Newspapers occasionally covered clashes between pastors and communities over witchcraft accusations. Activists warned about the dangers of witch-hunting. Yet, the mystique of Oyedepo’s moment at Ota remained.

Cultural Ripples:

In Nollywood films, in village conversations, in online debates, the idea of confronting witches became a shorthand for bold faith. Oyedepo’s name was almost always in the sentence.

Symbolism Over Historicity

Whether or not every detail of the event can be historically verified matters less than what it symbolizes. In narrative nonfiction terms, it is a parable lived out in flesh and bone. It reveals the tension between modern Christianity and traditional belief, between spectacle and sincerity, between fear and liberation.

For Oyedepo, the act was consistent with his theology: witches and devils are no match for faith. For Nigerian society, it was a flashpoint—a reminder that religion is never just about doctrine, but about how people make sense of the unseen forces they believe govern their lives.

Lessons, Legacies, and Lingering Questions

Many years later, the altar call for witches is still quoted. Sermon clips resurface. Blogs retell the tale. Debates reignite. Some dismiss it as fiction, others as exaggeration, others as divine reality.

What remains undeniable is that it shaped the identity of Living Faith Church. It branded Oyedepo as not just a preacher of prosperity, but a commander in spiritual warfare. And it cemented Ota as a stage where Nigeria’s old fears and new faiths collided.

The legacy is double-edged. On one hand, millions found confidence and boldness in a God who supposedly shamed witches publicly. On the other, the narrative risks fueling witchcraft accusations that can harm vulnerable people in villages and communities.

Thus, the story continues to walk a tightrope—between faith and fear, liberation and superstition, inspiration and danger.

Conclusion: The Question Still Echoes

That day in Ota, the silence was shattered by a question that dared the darkness to step into light. Whether myth, memory, or miracle, the altar call for witches became part of Nigeria’s religious DNA.

To this day, the question hangs in the air: “Is there any witch here?”

It is no longer just Oyedepo’s question. It is Nigeria’s—echoing across pulpits, villages, films, and hearts. It asks not just whether witches exist, but how a society shaped by fear, faith, and folklore chooses to confront the shadows within.

Discussion about this post