In Nigeria, power and piety have always shared the same stage, yet few ever pause to notice the cracks beneath the spotlight. What happens when ambition meets altar, when the corridors of authority brush against sacred ground?

The questions linger, unspoken but felt in the uneasy glances, in the conversations that falter when certain names are mentioned. Somewhere between devotion and design, between ceremony and calculation, a fault line has formed—a quiet tremor that promises to ripple far beyond the walls of any church.

This is not a story of sermons or speeches; it is a story of boundaries, influence, and the subtle choreography of who is allowed to step where. And it is here, in the shadows of expectation and authority, that the narrative waits—daring the reader to look closer, to follow the tension that threads through faith, politics, and the spaces they both claim.

The Context: Politics and Pulpits in Nigeria

In Nigeria, the boundaries between faith and governance have long been porous. Politicians frequent places of worship, churches host thanksgiving services for infrastructure, and public officials are often celebrated from the pulpit. Often, the pulpit itself becomes a site of both reverence and strategy. While attendance at church has been virtually universal for political actors, what has grown problematic is the slide from being worshippers to being orators at worship.

The (Church of Nigeria) CoN’s new policy must be read against a backdrop of increasing alarm within the church leadership about this slide. A recent article in The Nation noted that “political campaigning or commentary in church services across Nigeria is fairly common” and that the pulpit risked being turned into a campaign ground. The trend, according to church insiders, was accelerating: election seasons brought amplified displays of power inside pulpits—thanking God while thanking voters; offering prayers while offering pledges.

Yet the church has always had other roles. Beyond worship it plays moral commentary, social mobilisation and national engagement. Unlike a purely private religious forum, many Nigerian churches act with public function: they speak out on governance, human rights, and national crises. That duality—evangelical centre and civic actor—makes the question of the pulpit all the more complex. When a politician addresses a congregation from the lectern, the church’s dual identity is pressed into tension: is it delivering spiritual formation, or inadvertently becoming a political stage?

Within that space, the CoN has now drawn its line. The lectern, the altar, the consecrated space are no longer available for unchecked public address by political actors. Their decision exposes the friction between a church body seeking neutrality, and a political culture used to mobilising power, presence and praise in religious settings.

The Directive: What the Church of Nigeria Has Ordered

In July 2025, the CoN formally articulated a set of guidelines banning politicians and government officials from speaking from the lectern or altar during worship services. The key points of the directive are:

Politicians may attend services, but they shall not use the church lectern/altar/pulpit to address congregants with political speeches or partisan remarks.

Church leaders are instructed to avoid eulogising or glorifying public officials in a way that may compromise the church’s neutrality.

Guests expected to speak must engage in prior consultation with church leadership; they must be plainly informed that the church is not a campaign venue.

The lectern is designated for the reading of the Word of God; using it for political discourse undermines the sacredness of the space.

Dioceses are mandated to apply these protocols uniformly and report compliance.

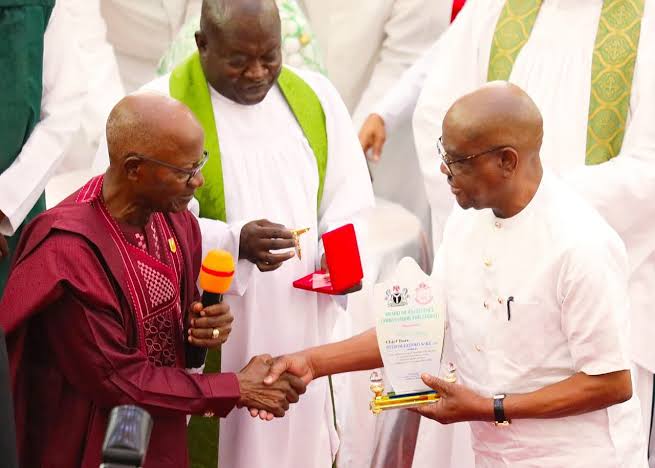

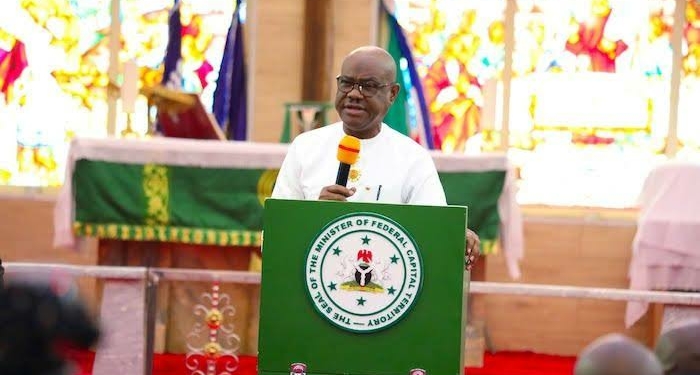

A memo from the Henry Ndukuba, the Primate of CoN, framed the move as “the Church must be a place of worship, not a campaign ground.” The directive was made in the aftermath of a highly visible thanksgiving service by Nyesom Wike, the Minister of the Federal Capital Territory, which many observers cited as a tipping point.

From metropolitan capitals to rural parishes the expectation now is clear: the altar is no longer open to political oratory without prior vetting; the church must guard its sacred form. The decision is doctrinal, symbolic, and procedural: declaring that ecclesial spaces belong to spiritual duties, not electoral strategies.

The Trigger: Why the Church Moved Now

The timing of the CoN’s move is not incidental. It reflects a confluence of public controversies, internal reflection, and ahead‑of‑election anxieties. The watershed event appears to have been Wike’s thanksgiving service at St. James’ Anglican Church, Asokoro in Abuja.

The minister reportedly used the pulpit to address political foes, referencing election outcomes and underlying power dynamics. Many within the church concluded that the incident exposed a broader pattern: politicians were increasingly treating the church service as part of their campaign apparatus.

Beyond this singular event, church leaders have long been uneasy about the way worship has merged with politics. Interviews compiled by The Nation framed it this way: “The pulpit is not a platform for political campaigns. It’s meant to pull people out of sin, not push political agendas.” In practical terms, this meant church leaders had identified risk: congregations divided, worship disrupted, spiritual mission overshadowed by partisan spectacle.

The upcoming 2027 election cycle in Nigeria further sharpened the urgency. As political actors intensify their outreach, worship gatherings present rich terrain: large gatherings, media coverage, photo‑ops, public declarations of gratitude—all of which feed into political messaging. The church’s leadership appears to have judged that failure to act would strip it of moral credibility, reduce its pulpit to mere campaign stage, and alienate worshippers who seek sanctuary from the noise of politics.

Thus, the directive is reactive and proactive: reactive to high‑profile abuse of pulpits, and proactive to forestall future erosion of sacred spaces. By drawing the line now, the CoN signals both self‑preservation and a reassertion of its spiritual identity.

The Human Factor: Clergy, Congregants and Politicians

Behind the policy are real people: parish priests worrying about their sermon being overshadowed by a politician’s address; worshippers uneasy that their Sunday service turns into a press conference; and public officials who have grown accustomed to the altar as a stage. The directive forces new dynamics.

For clergy, the memo means greater vigilance. They must now vet guest speakers, refuse mics if required, and diplomatically curtail extraneous speeches. In the Niger Delta Province memo, bishops warned clergy to “courteously retrieve the microphone or turn it off” if a politician begins a speech unsanctioned. That shift places pastors in the awkward space of enforcing discipline among powerful visitors—no small challenge in a system where social networks and patronage are deeply entangled.

For congregants, the move may feel like reclaiming their worship space. Many Nigerians had grown weary of Sunday services doubling as campaign rallies. A churchgoer in one interview described attending a thanksgiving service where platform presentations of infrastructure staff, photo‑ops and political speeches overshadowed the sermon. For them, the directive offers an affirmation: worship is first, politics second.

For politicians, the new rules introduce a new etiquette. They can attend, and may be acknowledged, but not take the lectern for speeches, nor rely on the church as a venue for rallying support. The church is drawing a line between presence and oration. Whether all political actors will comply remains an open question.

At the heart lies a human tension: faith spaces are built on reverence, community, and transcendence. Politics is built on ambition, persuasion, and presence. When politics invades faith space, it disrupts the flow of worship; when faith imposes rules on politics, it challenges the political habit of spectacle. The CoN’s directive is a human artefact of that tension.

The Theological and Liturgical Rationale

Why does the church care about who uses the pulpit and how it is used? The answer crosses theology, liturgy and ecclesiology. In Anglican tradition, the lectern and pulpit are not neutral furniture: they are ritual loci, consecrated spaces from which the Word of God is read and preached. When a politician appropriates the lectern for campaigning, the symbolic integrity of worship is compromised.

The directive explicitly states that the lectern is “consecrated for the reading of God’s Word” and should not be used for political discourse. The act of reading scripture, preaching, administering sacraments takes place in that space; any outsider speech breaks the sacramental grammar. Church leaders argue that once the pulpit becomes a campaign stage, congregants are no longer gathered for worship but for spectacle—and the spiritual mission is lost.

Moreover, theology underscores the difference between worship and endorsement. While churches can pray for leaders, they are not endorsers of policies or candidates. Allowing political speeches from the altar risks turning the church into a partisan actor rather than prophetic witness. As the memo puts it: the church must “diligently avoid speeches, conduct or events that may incite division or foster political bias within the body of Christ.”

The Christian message, particularly in the Anglican tradition in Nigeria, espouses the prophetic role: speaking truth to power, accompanying the poor, advocating for justice. That role is distinct from being a campaign platform. By reclaiming the altar, CoN seems to assert that its mission is above the vicissitudes of electoral politics.

Liturgy also matters. Sunday service is patterned, rhythmic, communal. It is not meant to mimic a political rally. When worship becomes punctuated by campaign speeches, the integrity of the liturgy is eroded. The guidelines therefore aim to restore the liturgical order: scripture, sermon, prayers—without slipping into manifestoes or endorsements.

Implications for Church‑State Relations

The directive also has broader implications for how the church positions itself in relation to the state and to power. Nigerian churches often operate in a space where power and worship intersect: infrastructure projects launched at thanksgiving services, governors inaugurating church buildings, ministers receiving blessings from bishops. The CoN’s move signals a recalibration: yes, we engage with the state—but not on the state’s terms.

By insisting on neutrality, the church protects itself from capture by political factions, and preserves credibility among worshippers who may not align with a particular party. In a country where religion is deeply entwined with identity, the danger of a church perceived as partisan is real: it risks alienating parts of its flock and losing its role as moral voice.

The rule also challenges political actors: when Sunday becomes off‑limits for campaigning, they must redirect their strategies. That could reduce the religious spectacle dimension of politics, forcing campaigns into secular venues. Over time, that may help to delineate religious and political spheres more firmly—a distinction often blurred in Nigerian public life.

However, the directive does not remove the church from public life. The CoN explicitly affirms that it remains open to leaders, remains engaged with social issues, and will hold governments accountable. The difference is the forum and form. The sanctified pulpit is not for partisanship; engagement, yes — but not spectacle.

This moves the church toward a stance of prophetic distance rather than partisan proximity. It suggests that while the church dialogues with power, it does not dance with it on its own stage.

Challenges and Critiques

Despite clear intent, the directive faces multiple challenges in practice. Enforcement across the vast CoN network of dioceses and parishes will vary. Some bishops may be more committed than others. Pastors may lack the will or capacity to refuse microphone requests from powerful visitors.

There is also the issue of informal speech: politicians may attend church events, give informal greetings, pose for photos, make off‑the‑record comments. These may not technically breach the lectern rule but still bring political messaging inside the church. A memo may restrict the lectern, but it cannot fully ban influence.

Critics argue that the church’s decision is overdue, or even cosmetic. Some pastors and worshippers believe that the problem runs deeper: often, the real issue is dependency—on politicians who fund building projects, on votes and favour. Unless the economic dependencies are addressed, the pulpit will continue to bend to power.

Legal scholars note that the directive is internal to the church; there is no civil law forbidding politicians from addressing congregations. Churches therefore remain vulnerable to reputational risk, more than legal risk. Whether congregants or civil society will hold churches accountable remains to be seen.

Another critique: what about the possibility of selective enforcement? If a politician aligned with a pastor’s ambition is allowed to speak and others are shut out, the policy could become a new arena for bias rather than a guard against it. Transparency and consistency will be crucial.

Wider Significance: Religion, Politics and Public Square

Beyond Nigeria, the CoN’s move is emblematic of a global question: how should religious institutions relate to politics in moments of mass mobilisation and social media spectacle? In many parts of the world, houses of worship have doubled as stages for governance and rhetoric. The Nigerian example shows a church pushing back.

The move also invites reflection on the nature of public religion. In Nigeria, religion is public, visible, audible. Politicians stage church houses, pastors endorse candidates, services are televised. The pulpit is high‑profile. The CoN’s directive troubles that expectation: yes you may enter the church, but you may not commandeer its focal point.

Furthermore, the directive raises questions about the authenticity of worship in environments saturated by politics. When the congregation wonders “why is he thanking God and asking for votes?” the spiritual mission is muddied. The church’s attempt to reclaim its liturgical integrity matters for all believers, whatever their political alignment.

Finally, the move may contribute to civil society’s expectation of institutional independence. If churches can draw clear lines, so might other institutions: universities, civil society groups, media. The notion that a space exists free from partisan mobilisation is attractive in a context of polarisation. The church’s boundary‑drawing could serve as precedent.

What Comes Next: Implementation, Monitoring and Culture Change

The directive may be issued, but its impact will depend on follow‑through. Each diocese must translate policy into action: update parochial handbooks, train clergy, enforce microphone policies, monitor guest speeches. The memo from the Niger Delta Province demanded that all clergy be briefed and parishes informed. These are administrative steps—but cultural change tends to lag.

Monitoring and accountability will matter. Are there instances of mic retrieval when an unsanctioned speech begins? Will congregants call out pastors who give special positioning to politicians? Will church bulletins and programmes reflect the new boundary? Will sponsorships and donations redirect? These practical markers will reveal whether the policy stays on paper or becomes lived practice.

Moreover, pastors and public officials must negotiate new rhythms. Politicians must identify new venues; pastors must push back with diplomacy and firmness; congregations must recalibrate expectations. Over time, worship services may become quieter, less media‑driven—and perhaps more spiritually centred.

One potential indicator: the next election season. Will politicians respect the pulpit’s boundary, or will they test it? Will churches issue reports on compliance? Will public scrutiny track whether the church remains the pulpit or reverts to the podium? How the CoN navigates those questions will determine whether the policy is lasting or symbolic.

Leaving With This

The lines drawn at the altar are more than rules—they are a quiet rebellion against the way power insinuates itself into places meant for reflection, devotion, and conscience. In a nation where politics and piety have long danced too closely, this ban is a ripple that threatens to unsettle old rhythms, forcing both the faithful and the ambitious to confront the boundaries they have taken for granted. The Church has reminded the nation that some spaces are untouchable, not through force but through the weight of principle, and that reverence cannot be borrowed or bargained for.

As the final notes of hymns dissolve into the stillness, the altar remains, steadfast and unyielding—a silent witness to ambition and devotion alike. It holds a quiet authority, reminding all who enter that some spaces are not to be conquered, some voices not to be amplified at will. In its patience, it speaks a truth louder than any speech: influence may press against the sacred, but the altar endures, guarding what is eternal, demanding reflection, and challenging the conscience of a nation to recognize that not everything is negotiable.

Discussion about this post